political science

How Progressivism Enabled the Rise of the Populist Right

Progressives will look askance at these policies, decrying them as racist and fleeing to Green or other political alternatives.

Right-wing populists have won an unprecedented 57 seats in elections to the European Union’s Parliament, up from 30 in 2014. In Hungary, Viktor Orban’s Fidesz won a majority of 52 percent. In Italy, Matteo Salvini’s Lega topped the poll at 30 percent, in Britain, Nigel Farage’s Brexit Party won, while in France, Marine Le Pen pipped Emmanuel Macron 23 percent to 22 percent. While not quite the populist surge some feared, right-populist momentum continues. Meanwhile, the mainstream Social Democrats and Christian Democrats saw their combined total drop below a majority for the first time, from 56 percent in 2014 to 44 percent as Green and Liberal alternatives gained.

What few have noticed is that these results, especially in Western Europe, reflect a continuing blowback against the excesses of the post-1960s liberal-left. They also reveal how the mainstream has adapted to the populist challenge by tightening immigration, which has reduced the appeal of national populism in many northern and western European countries since its 2015-16 peak. This adjustment by the main parties has alienated some left-liberals, whose shift to Green or liberal alternatives hints at a new polarization that may be moving Europe in an American direction.

Since the EU has little power compared to nation-states, EU elections are a symbolic vote, based on lower turnout than national contests. Yet the results are an important bellwether of western public opinion, and affect national conversations. In 2014, many were shocked by the performance of the French Front National, Danish People’s Party and UK Independence Party, when these parties achieved nearly 30 percent of the popular vote in their countries. So began the ‘populist moment’. While populist share has declined in France, Denmark and a number of northern and western European countries over 2014, it has emerged in places where, in 2014, it had been absent or weak, like Spain, Germany or Estonia; or in abeyance, as in Italy.

It’s Not the Economy, Stupid

There’s a comforting myth that voters are electing right-wing populists because they feel ‘left behind’ by the global economy and uncaring politicians. All that’s needed is to redistribute some wealth, grow the economy and devolve power and all will be fine. In fact, there is little evidence to back up these assertions. In numerous surveys I have analyzed, immigration attitudes and salience, not economic circumstances or even anti-elitism, are what best explain why people vote for right-wing populists.

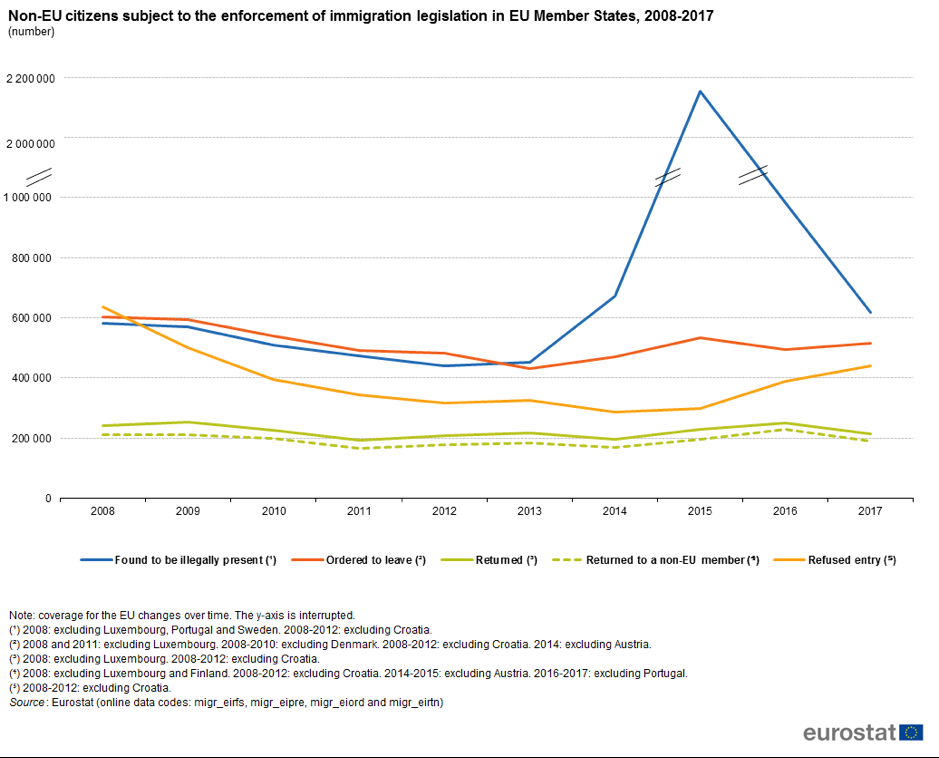

Figure 1 shows what happened to non-EU illegal migration from 2013. Notice the rise in the blue line from 2013 to 2015, followed by a subsequent fall.

Figure 1.

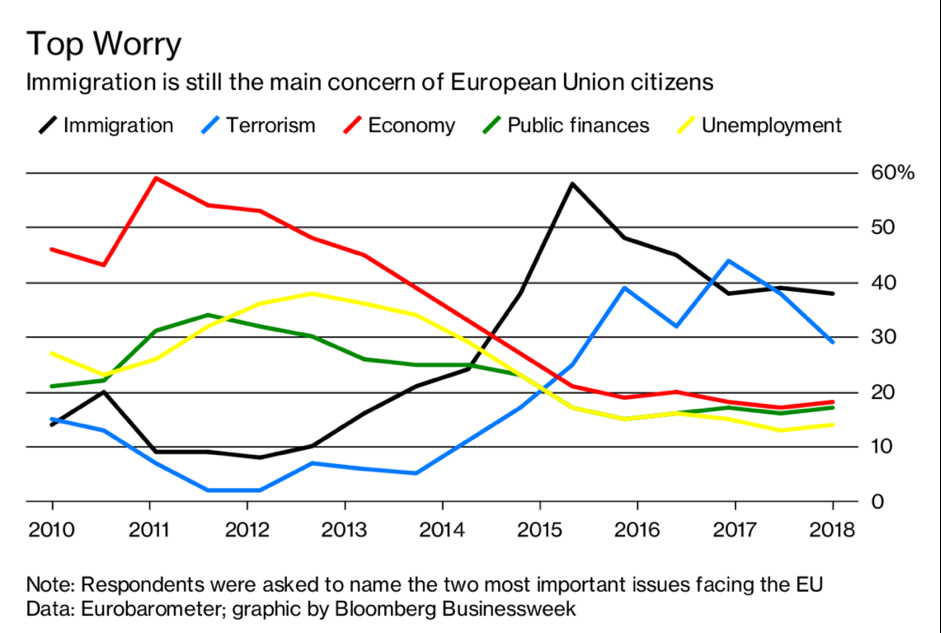

What this rise produced, as the black line in figure 2 shows, was an increase in the share of Europeans who said immigration was one of the top two issues facing their countries, and the European Union as a whole. The ‘most important issue’ question is a measure political scientists term immigration salience. It’s not that people went from wanting more immigrants to fewer, a disposition tied strongly to ideology. Rather, among the majority who already wanted lower numbers, a larger share ranked immigration among their top priorities than in the years prior to 2013.

Figure 2.

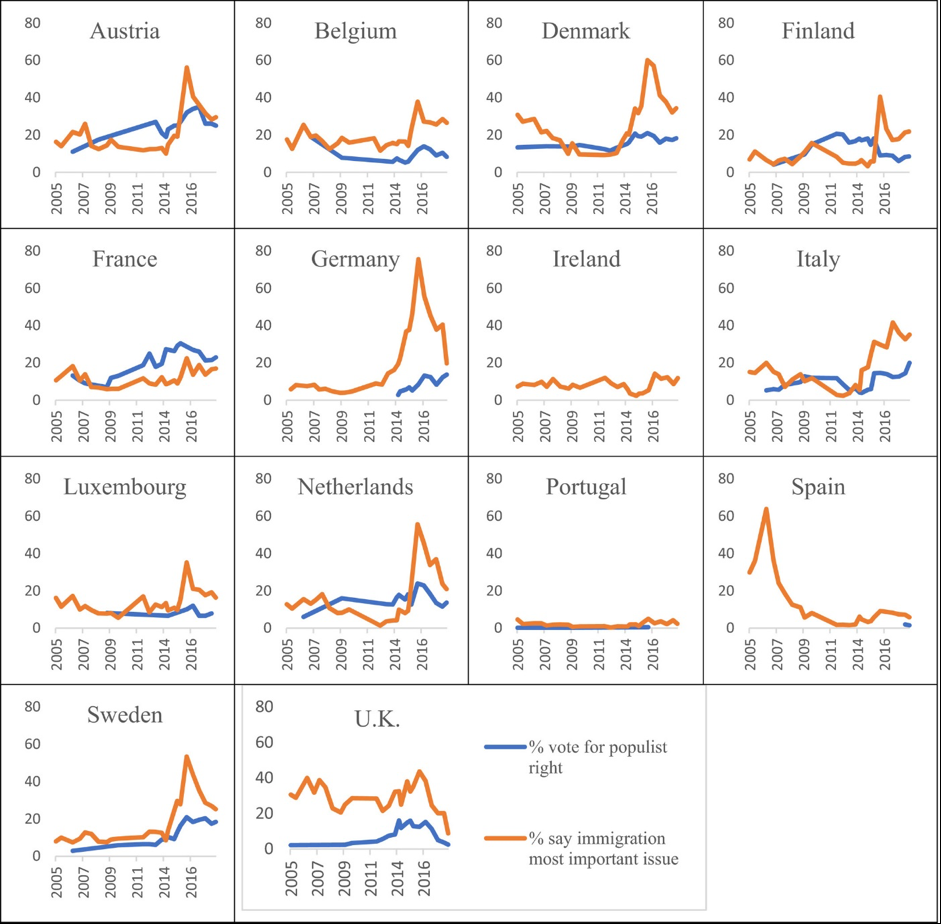

This in turn gave populism a shot in the arm. Consider, in figure 3, how immigration salience corresponds to populist right support, courtesy of an article by James Dennison and Andrew Geddes of the European University Institute. While not always easily visible due to the different magnitude of the two trend lines, there is a significant over-time correlation in 9 of 10 major West European countries between immigration salience and populist support. This saw populist right support peak with the height of the migration crisis in late 2015, then gradually subside.

Figure 3. Immigration Salience and Populist Right Party Support, West Europe, 2005–16

The Progressive Roots of Right-Wing Populism

The populist upsurge ultimately originates from two major sources: globalization and the rise of left-liberalism. Ninety-seven percent of the world’s population growth is taking place in the developing world, which is still in the early stages of its transition from high to low birth rates. Meanwhile, the global North is aging and beginning to experience native population decline. Globalization—better connectedness across borders—opens up the possibility of increased migration from the poor growing parts of the world to the rich regions. However, while globalization produces an increased flow of goods and capital, it doesn’t guarantee people can move, for we live in a world of controlled borders. Singapore is highly dependent on world trade, for example, but strictly limits immigration. Indeed, East Asia as a whole has essentially experienced globalization without immigration. Where immigration is permitted, it’s generally temporary and the right to work isn’t bundled with national citizenship.

The key difference, therefore, is the West’s demographic openness, which is a result of two cultural revolutions. First, the shift from national to cosmopolitan liberalism. Liberal political theory, which developed in the 18th and 19th centuries, took it for granted that nations and borders existed, seeking to delineate the rights of individuals within bounded nation-states. After 1945, western judiciaries interpreted international human rights and refugee conventions in an increasingly expansive, transnational manner, whereas East Asian countries took a much narrower approach to the same non-specific international codes.

An analogous spirit built a supranational institution, the European Union, which, after 1992, enshrined the right to live and work across borders. The EU also worked toward a diminution of national powers through slogans such as a ‘Europe of the regions’ (thereby sidelining nations), ‘ever closer union’ (in which the centralization process was defined as an end-in-itself), the removal of national policy vetoes through Qualified Majority Voting (QMV) in EU institutions, and the establishment of EU law as supreme over national law.

The New Left and Immigration

The second revolution was the cultural turn of the left, from a focus on class and economics to a concern with disadvantaged race, sex and gender groups, and their associated social movements. This has had far-reaching effects. How so?

Consider two faces of contemporary left-liberalism: the ‘hot’ outrage culture and ‘cool’ political correctness. The two spring from the same ideology, which holds that racial, sexual and gender minorities require protection and therefore governments should take no action which might offend the most sensitive minority person imaginable. The callout culture has had only limited effects off-campus (though this is beginning to change in the Anglosphere countries as ‘woke’ staff begin to spread their mores within private and public-sector organisations and right-wing media circulate stories of campus excess). But what is far more important off-campus is political correctness.

This quieter, routinized form of left-liberalism commandeered social norms to limit the ability of mainstream political parties to address the concerns of citizens who wanted lower immigration and a defense of their version of national identity. The definition of racism underwent what Nick Haslam terms ‘concept creep,’ expanding beyond its normal meaning to encompass any discussion of immigration or a positive expression of white majority identity. While the share of the world composed of immigrants has risen only modestly, western openness – a result of both the cosmopolitanization of liberalism and cultural turn of the left – permitted south-north immigration to increase steadily from the 1960s.

As I discuss in my new book, Whiteshift: populism, immigration and the future of white majorities, the narrowing of the Overton Window of acceptable debate opened space for populists. When Soviet department stores stocked only one kind of pants, a black market sprang up to supply the blue jeans people desired. Likewise, when mainstream parties are aligned on immigration, political black marketeers will emerge to supply the lower levels of migration many seek.

While mainstream parties must take a stand against real racism—American third-party segregationist George Wallace got 13 percent of the vote in 1968 but was rightly ostracized—the taboo against discussing migration has nothing to do with ensuring equal rights for citizens regardless of race. While some minorities may be offended by calls to limit immigration, most are not, and politicians should heed the ‘reasonable person’ rather than ‘most sensitive person’ standard when enacting policy.

For instance, in 2013, Swedish immigration minister Tomas Billström was attacked in the media for suggesting Sweden needed to debate immigration levels. Then in 2014, the populist right Sweden Democrats burst onto the scene, winning 13 percent of the vote. Mainstream politicians had their parliamentary seats unscrewed and moved to avoid sitting next to the populists, who were treated like a disease. Then came the 2015 Migration Crisis. With the Sweden Democrats hitting 20–25 percent in the polls, the centre-left government began scaling back its refugee intake and introduced ID checks at its border with Denmark. We see very similar dynamics in Germany, where the Alternative for Germany (AfD) emerged in 2015, and in the US, where Donald Trump was the only one of 17 Republican primary candidates willing to make immigration central to their pitch.

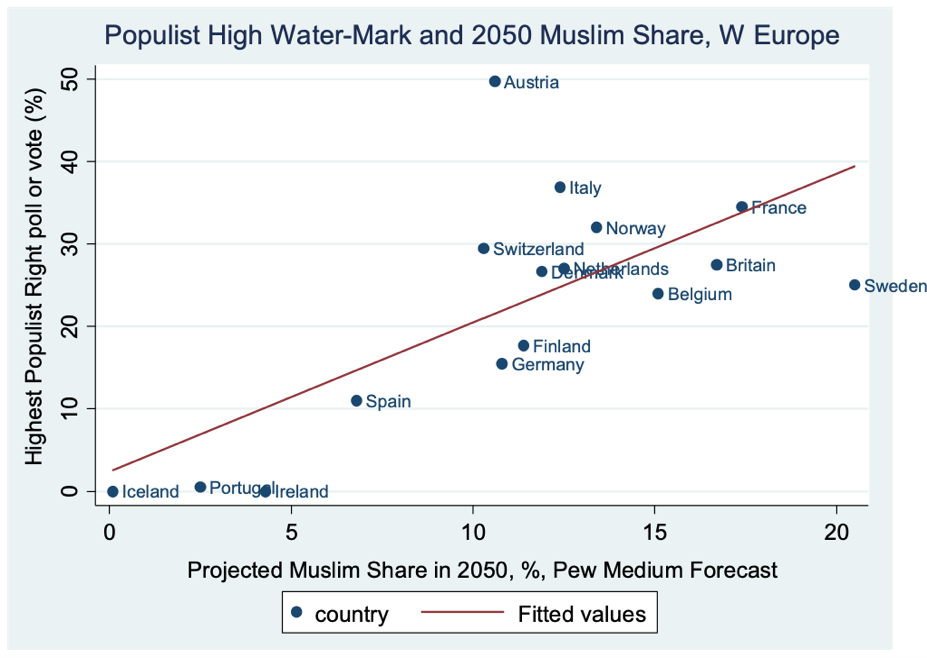

We are at the beginning, not the end, of a demographic shift in Europe that will see white majorities decline to half the total in many West European countries by the end of the century. While the Muslim share of Western Europe will—despite the scaremongers—not reach a majority, and may ultimately decline through intermarriage, Pew projects that several major western countries will see their Muslim share triple by 2050, reaching 20 percent in Sweden and 17 percent in Britain. The level and rate of Muslim increase, as captured by Pew’s 2050 projections, is therefore correlated with populist support, as shown in figure 4.

Figure 4.

The situation is different in ex-Communist EU states, where Muslim growth is minimal and populist right support stems both from weaker social liberalism and the traumas of history, which incline voting publics toward an acute sensitivity to foreign invasion or domination.

In view of these seismic changes, mainstream parties need to carefully manage migration. Immigration, as survey experiments show, unsettles the cultural security of conservative ethnic majorities and minorities who are attached to the traditional ethnic composition of their nations. The good news is that populist support in the West is tied to an issue under government control, not hostility to the democratic system. So long as mainstream parties manage the inflow of immigrants, they can keep the populist right at bay, as demonstrated by the centre-left Danish Social Democrats and centre-right Austrian People’s Party (ÖVP). The post-2015 decline in immigration and shift of mainstream parties to the right on this issue is a major reason why populists have declined somewhat in many northern and western European countries since 2015. Progressives will look askance at these policies, decrying them as racist and fleeing to Green or other political alternatives. Yet these liberal alternatives remain modest forces which don’t threaten democratic stability and can function as coalition partners for the mainstream parties.

So long as progressive norms don’t paralyze the mainstream parties on immigration, as they did in the very recent past, democracies can successfully respond to political demands, limiting populist influence.