News

The Real Ballot Question in South Africa: How to Keep the Country from Falling Apart

Corruption, escalating unemployment, social unrest, and failing public infrastructure plague the nation.

South Africa’s sixth election since the introduction of universal suffrage in 1994 takes place on May 8. It has been 25 years since the country cast off the moral abomination of apartheid. But the noble and worthy dreams that took flight in the era of Nelson Mandela have been crushed by reality. Indeed, the dreadful irony is that Afrikaner nationalists’ dire predictions about majority rule seem to have come true.

The country is in a parlous state: A recent Bloomberg report found that on a wide range of indicators, South Africa has done worse over the last five years than any other country in the world save those in a state of war. Corruption is rampant at every level, starting with the police. The power cuts that began in 2007 have gotten steadily worse. And although the government has managed to keep the lights on for the election campaign, the most optimistic forecast is another five years of intermittent supply. This in a country that, in 1994, had an oversupply of electricity at some of the cheapest rates in the world. Aggressive affirmative-action policies have seen the skilled and experienced whites who once ran the power stations dispersed around the world. In their place are many thousands more workers on higher salaries but without sufficient technical knowledge. Eskom, South Africa’s national power supplier, has a debt burden so large that it cannot even pay the interest on its debt, let alone the principal.

Unemployment, which stood at 3.7-million when the African National Congress (ANC) came to power in 1994, now stands at nearly 10-million, and recent data show that South Africa is the most unequal country in the world when it comes to income, consumption and wealth. To be sure, the architects of apartheid bequeathed a society that already was not only racist, but unequal. Yet the situation has become exacerbated by the rise of a vast, overpaid bureaucracy and a corrupt political elite. The program of state-mandated black “empowerment” requires that companies effectively give away equity to silent partners who have no function but to balance the racial books. Few companies are willing to invest on such terms, so even many fabulously rich mines have been closing down, with jobs being lost in the process. South Africa is now in its fifth consecutive year of falling real incomes.

Social unrest is rampant. More than 80 major public-works projects are stalled because they are besieged by local syndicates demanding a share of operating profits. A major cyclone hit the province of KwaZulu-Natal recently, killing 70. The response of local public-sector workers was to cut off water supplies to the wealthier suburbs and threaten electricity cuts, too, as a means to leverage the crisis to advance their own demands. The government, whose army and police force both have become ineffective in recent years, seems powerless to stop such behaviour, even if it wished to.

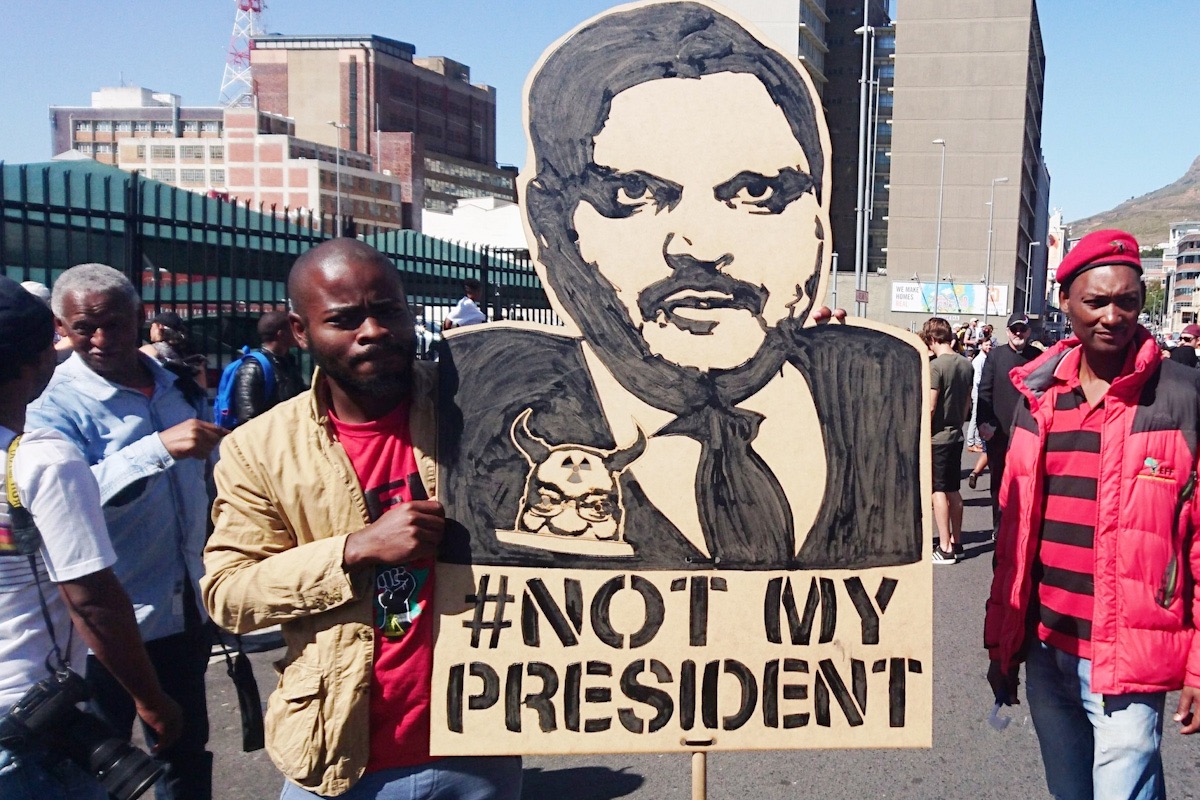

The election itself is a foregone conclusion. The ANC, which still leans heavily on its credentials as the anti-apartheid party of liberation, likely will win nearly 60% of the vote. Polls suggest that the liberal Democratic Alliance will lose ground and that the extreme-left populist Economic Freedom Fighters will double their vote. The ANC government already has committed itself to legislate the expropriation of property without compensation, the growth of a completely unaffordable national health service, and a variety of other populist policies. But even as it is , government debt is climbing toward 60% of GDP, and two credit-ratings agencies have consigned the country’s debt to junk status. The main teachers’ trade union now sells teaching jobs to the highest bidder—and intimidates or even kills those who expose such deals. Hospitals and schools have decayed below apartheid levels. In many cases, medicines and blankets are sold off by corrupt hospital staff. Throughout the country, small towns are collapsing because ANC municipal cliques have stolen the available funds, leaving local authorities unable to repair or replace dysfunctional infrastructure, which is why one can see sewage flowing in the streets.

Such a situation might seem to augur well for the country’s centrist official opposition, the Democratic Alliance, which has gained steadily over the last 25 years. But this time around, it chose a young and inexperienced leader, Mmusi Maimane, who has failed to energize black voters or even maintain the party’s existing mainly Asian, “Coloured” and white constituency. If the DA goes backwards on May 8, he could lose his job and the party would be thrown into turmoil.

Meanwhile, ANC leader Cyril Ramaphosa retains a 60% approval rating, and faces no viable rival within his party. He is an amiable and well-meaning man, but weak and quite unable to control the various ANC factions. Not only rank-and-file South African voters, but a good number of white businessmen (and even editorial writers at The Economist), placed high hopes on Ramaphosa following the 2018 resignation of Jacob Zuma. But there seems little prospect that he can fulfil such expectations. The ANC election list is studded with convicted criminals found guilty of grossly corrupt behaviour. These include Deputy President David Mabuza, the subject of a major New York Times exposé, and ANC Secretary-General Ace Magashule, the subject of a 2019 book entitled Gangster State: Unravelling Ace Magashule’s Web of Capture. (Magashule’s supporters stormed into bookshops to burn copies of the book, and Magashule has threatened to sue, though as yet there is no sign of a writ.)

In theory, Ramaphosa could be forced out of the ANC leadership by forces loyal to his corrupt predecessor, Jacob Zuma. But even Ramaphosa’s foes realize that his popularity is about all the ANC has left. Perhaps the best case scenario is that, having reaffirmed his mandate, Ramaphosa could have South Africa apply for an IMF bailout once the elections are over. But the ANC is ideologically opposed to this, knowing that such a move would mean structural reform and a war on corruption. So the more likely scenario involves the government seizing pension funds and whatever other lumps of capital it can find, or forcing financial institutions to buy government bonds, as a means to strong-arm its way out of the mess—even though this would simply accelerate capital flight and push away the foreign investment that Ramaphosa is desperate to attract.

Another possible scenario is more apocalyptic. The downward spiral may be so pronounced that an increasingly desperate political elite will throw all blame on whites and Asians (who represent 9% and 2.5% of the country respectively), setting off the sort of full blown meltdown witnessed under Robert Mugabe in Zimbabwe. I am far from the first journalist to muse about this, and such fears have been motivating large-scale emigration by skilled and wealthy members of both communities for years.

Another cataclysmic scenario: The government will continue to lose control of the country, leading to a breakup of South Africa into its component regional parts. Frans Cronje, head of the liberal Institute of Race Relations, foresees a future in which a small white and black middle class will continue to live in a prosperous bubble in a few of the bigger cities; while the countryside is ruled by rapacious chiefs, and the rest of urban South Africa is run by murderous gangs. Some would argue that we aren’t far from that now.

Finally, it should be noted that while South Africa’s legacy of apartheid makes it unique, it is dealing with the same problem of uncontrolled migration that afflicts other, far wealthier nations. Border control has broken down, with the result that millions of Zimbabweans, Malawians, Congolese and others have flooded into a country that already doesn’t have enough jobs. Polls show that massive majorities say there are too many foreigners in the country, and some sporadic outbreaks of xenophobic violence have broken out. The government is desperately embarrassed by this situation, but has no means of effectual response. There is a terrible risk of truly catastrophic scenes of violence against new arrivals.

Needless to say, this is not the South Africa that Nelson Mandela and a happy world greeted with enthusiasm in 1994. It always was asking a lot of the ANC elite to step into the ruling role following generations of institutionalized white supremacy. But they have done far worse than anyone expected. If Ramaphosa has the nerve to seize the situation after the election, force through major reforms and start throwing his corrupt colleagues into jail, the situation could still conceivably be saved in the long run. But that is asking an awful lot of a 66-year-old man who still seems trapped within old-style African nationalist platitudes. The sad truth is that he seems more likely to preside over my country’s continued decline into poverty and chaos than avert it.