Intelligence Research

The Mismeasurements of Stephen Jay Gould

Gould believed this bias was rampant in particular scholarly fields, and the most prominent target for his criticism in The Mismeasure of Man was the study of intelligence, especially IQ testing and the genetics of mental ability.

Stephen Jay Gould, the famous 20th century paleontologist, published his most celebrated work, The Mismeasure of Man, in 1981. Gould’s thesis is that throughout the history of science, prejudiced scientists studying human beings allowed their social beliefs to color their data collection and analysis. Gould believed that this confirmation bias was particularly powerful when a scientists’ beliefs were socially important to them.

The Mismeasure of Man by Stephen Jay Gould (1981)

Gould believed this bias was rampant in particular scholarly fields, and the most prominent target for his criticism in The Mismeasure of Man was the study of intelligence, especially IQ testing and the genetics of mental ability. And his analysis was not kind. Gould believed that there was a direct connection between the discredited study of skull measurements and the dawn of intelligence testing in the following generation. “But the IQ…relies upon assumptions…as unsupportable as those underpinning the old hierarchies of skull sizes proposed by nineteenth-century participants.” (Gould, The Mismeasure of Man, p. 210)

It may be surprising to readers to learn that I—a psychologist who researches human intelligence—agree with Gould’s principal thesis. Scientists’ pre-conceived notions about the things they study do guide their data collection and analysis. These beliefs guide scientists in choosing variables to measure, theories to test, statistical methods to employ, and more. This connection between beliefs and methods is a strong one. After all, if you believe that the universe is made of cheese, you’re going to build a cosmic cheese whiz detector.

And though I wish Gould had not targeted my field, The Mismeasure of Man provides a great deal of evidence that scientists’ pre-existing beliefs color their judgment—but not in the way he intended. Rather, the book is a perfect example of the sin it purports to expose in others. Gould’s Marxist political beliefs made him attack intelligence research because he saw it as a threat to his egalitarian social goals. Ironically, it was this allegiance to ideology over data that made Gould himself a classic examplar of a biased scientist.

Gould’s Politics

Gould openly admitted that he had strong social beliefs that colored his scientific views. In the introductory pages of the revised version of The Mismeasure of Man, Gould recounted his laudable efforts to fight discrimination and segregation in the 1950s and 1960s, both in the U.S. and the U.K. He explicitly made the connection between his political and social beliefs and his subject matter:

My original reasons for writing The Mismeasure of Man mixed the personal with the professional. I confess, first of all, to strong feelings on this particular issue. I grew up in a family with a tradition of participation in campaigns for social justice, and I was active, as a student, in the civil rights movement at a time of great excitement and success in the early 1960s. (p. 36)

He also admits that these beliefs are deep-seated and an emotionally important part of his life:

My father became a leftist, along with so many other idealists, during upheavals of the depression, the Spanish Civil War, and the growth of nazism and fascism. He remained politically active . . . and politically committed. I shall always be gratified to the point of tears that, although he never saw The Mismeasure of Man in final form, he lived just long enough to read the galley proofs and know . . . that his scholar son had not forgotten his roots. (p. 39)

Gould’s Trap for Himself

If Gould’s thesis is true for all scientists, and he sometimes wrote as if it is, then there is an obvious problem for him: he would be subject to the same biases, and his conclusions, like those of the scholars targeted in The Mismeasure of Man, would be inherently flawed—including his claim that all scientific analysis is biased. To prevent his thesis undermining itself, Gould performed an intellectual sleight of hand and redefined a critical idea. “Objectivity must be operationally defined as fair treatment of data, not absence of preference,” he wrote. (p.36) In this way, Gould used one of the rhetorical strategies of postmodernists: to redefine terms so that they do not have their everyday meaning, but rather a preferred meaning so that they do not threaten the person’s cherished conclusion.

By redefining “objectivity” so that he was allowed to still have preferences and biases while maintaining the patina of scientific respectability, Gould attempted to inoculate himself against the inherently contradictory position that he was in. This rhetorical strategy allowed him to separate preference from objectivity and claim that—somehow—he was capable of analyzing data “objectively” without undermining his conclusions. Gould was very much like the Marxist or postmodernist who believes that invisible power structures control every aspect of life—but who must somehow show that the postmodernist is special in her ability to escape the influence of these structures just long enough to see and resist them, thanks to their extraordinary intellectual courage and perspicacity.

In reality, Gould’s pious protestations of objectivity disguised a deceptive analysis of the scholarly record regarding intelligence research. What is astounding is how many people overlooked the contradictions of Gould’s position and accepted the analysis of intelligence research provided by a politically motivated snail expert.

Mismeasure’s Critics

Many scholars have criticized The Mismeasure of Man periodically throughout its 38-year history. For example, James T. Sanders stated that Gould’s attempt to link his argument to anti-racism was a ploy to smear intelligence scholars and Gould’s enemies as evil people. Arthur Jensen argued in 1982 that Gould misrepresented Jensen’s ideas and often demolished strawmen that no intelligence scholar believes, including the boogeyman of “biological determinism.” John Carroll showed that Gould understood neither the purpose nor interpretation of factor analysis (a statistical procedure often used to evaluate data from psychological tests) and that Gould’s attacks on factor analysis do nothing to alter the importance of intelligence tests, nor the mass of evidence—impossible to dispute—that they predict real-life outcomes.

Most criticism of The Mismeasure of Man was confined to the recherché world of psychologists who study intelligence. However, a new debate opened up in 2011 when a team of anthropologists argued that Gould’s analysis of the data on cranium measurements from 19th century scientist Samuel George Morton was flawed. Gould cast Morton as a racist who fudged his data to match his beliefs about white racial superiority because of a supposed larger skull capacity. Instead, the anthropologists argued, it was Gould who manipulated the data to support his biases.

This ignited a series of follow-up articles in the scholarly literature by authors taking a variety of positions regarding Morton’s data and Gould’s interpretations. Weisberg believed that the re-analysis was flawed and Gould was mostly correct. Kaplan and his colleagues claimed that Morton’s interpretations were flawed, but that Gould was incorrect in believing that he could discern Morton’s actions and motivations. Finally, Mitchell believed that Morton’s data were accurate and that the interpretations were colored by the racism of the era, but the claim that Morton subtly manipulated the data was a fiction created by Gould.

Though still unresolved, the debate shows that a critical analysis of specific sections of The Mismeasure of Man is warranted. After writing an article about Lewis Terman, an important developer of early intelligence tests, I decided that a 23-page section of The Mismeasure of Man would be a valuable section of the book to analyze. This section is Gould’s description and analysis of the Army Beta test, one of the tests that Terman helped create. The Army Beta was used in World War I to screen illiterate recruits for military service.

Having read some of the primary scholarly work about the Army Beta, I knew that some of Gould’s claims were inaccurate. However, I was unprepared for the level of pervasive deception that I encountered when I carefully checked Gould’s claims against the historical record. Moreover, I discovered overwhelming evidence that any pretense of Gould being “objective”—even if defined as “fair treatment of data”—is a farce. In The Mismeasure of Man, Gould elevates his biases to the status of uncontestable facts and to great lengths to hide the truth from his readers.

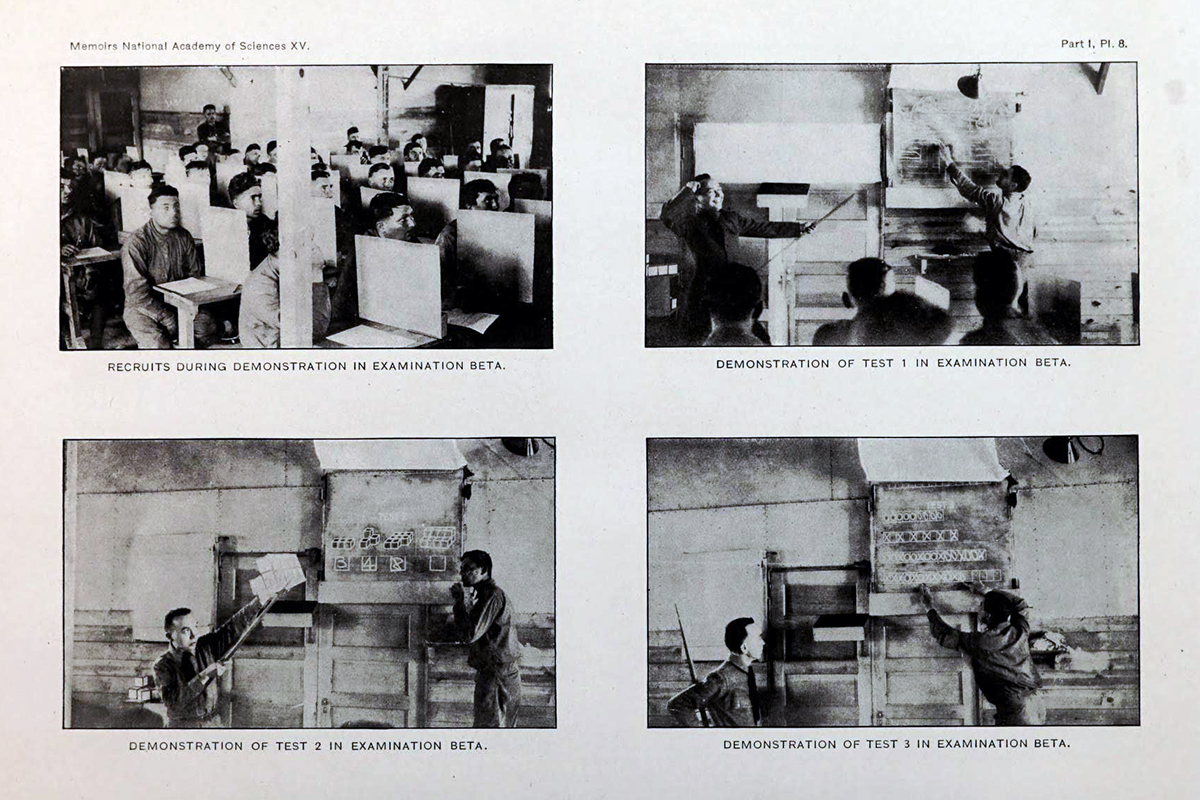

Army Beta examinees during World War I. The other three images are of examiners giving instructions and demonstrating how to complete the test. Source: Yerkes, 1921.

A Case Study in Gouldian Deception

The distortions of the scholarly record regarding the Army Beta range from the relatively benign to deliberate falsehoods. It would be impractical to catalog them all here, so I encourage interested readers to read my full analysis. What makes the analysis important is not the Army Beta itself—the test has not been used in research or practice for decades. Rather, Gould’s discussion of the Army Beta is emblematic of the way he distorted evidence, ignored data that contradicted his opinions, drew unwarranted conclusions, and even lied to his readers.

One of Gould’s favorite techniques for misleading his readers was exaggerating the importance of any unfavorable information about intelligence testing. For example, Gould emphasizes that testing conditions were sometimes far from ideal. Compared to the orderly testing programs that 21st century students experience, the administration of the Army Beta (and its companion test for literate men, the Army Alpha) was disorganized and unsatisfactory. The army testing program was underfunded, and the speed at which it started meant that available facilities were often not large enough to accommodate all examinees. Additionally, there was often a shortage of qualified examining officers. None of this is in dispute.

Gould seized on this information to portray the conditions as “…something of a shambles, if not a disgrace” (p.231) and claimed they invalidated the test results for many men. Gould’s supporting evidence is a single quote from “the chief tester at one camp” in which the officer complained that testing rooms were too overcrowded for some men to hear and understand the instructions. However, Gould cherry picked this quote (which was not from the chief tester at all) and ignored 13 favorable comments from officers at the same camp and the unanimously favorable opinions of the commanding officers at every camp.

The technique of building a negative conclusion on the basis of the slightest unfavorable data is epitomized in Gould’s analysis of the Army Beta instructions, which he called “Draconian” and “diabolical.” He also wrote that “…most of the men must have ended up either utterly confused or scared shitless.” (p.235) However, his support for this claim is a single secondary source that states some men struggled with producing written responses to the test questions. For Gould, “struggling” is the same as being “scared shitless.”

Gould consistently ignored evidence that contradicted his claim that early intelligence test creators gathered meaningless data using garbage tests. He neglected to mention that the test’s creators explicitly permitted administrators to give instructions and commands in foreign languages because this would threaten his belief that the Army Beta was particularly unfair to immigrants. (Italian and Russian, which were the two most common languages for immigrants in the U.S. at the time, were specifically mentioned by the test’s authors as being acceptable.) Gould also did not tell his readers about the strong evidence that Army Beta test scores predicted military job performance, a topic of several chapters in the only primary source that Gould consulted.

Gould also outright lied in several passages in The Mismeasure of Man. Among the falsehoods were:

- The army test creators had a “…poor opinion of what Beta recruits might understand by virtue of their stupidity.” (p.236)

- The claim that “vast numbers of men” earned zero scores on the Army Beta. (p.247)

- His statement that extremely low-scoring men had their scores “adjusted” so that they would receive a negative number for a score and that these men were “too stupid to do any items,” and were “dullards.” (p.246)

- It was “ludicrous to believe that [the Army] Beta measured any internal state deserving the label intelligence.” (p.240)

None of these statements is supported by the historical record. Indeed, in every case there is strong evidence to indicate the opposite is true.

Gould’s analysis of the Army Beta is not central to his book’s thesis, and if it were removed from future editions his main arguments would stand. But the tactics he used to impugn the creators of the Army Beta are used in every chapter to malign intelligence research. Throughout the book, Gould showed no compunction about exaggerating facts that support his beliefs, omitting important contradicting information, and lying to his readers.

All this shows that, far from a “fair treatment of data,” Gould’s analysis was guided entirely by his preconceived notions about intelligence research, which he saw as socially dangerous and irredeemably flawed. Inadvertently, Gould proved his own thesis correct: sometimes scientists are guided more by their beliefs than any data.

It is likely that Gould thought that his “rhetorical strategies,” if I can call them that (which have been outlined in more detail elsewhere), were justified because of his high-minded politics. In this way, he was not unlike the pious religious fanatic who believes that inventing stories of miracles is acceptable if it strengthens the faith of others and adds more believers to the flock. Instead of “lying for God,” though, Gould was lying for social justice.

For those who share Gould’s political and social views, there are better strategies for promoting an egalitarian agenda than linking it to dubious claims about scientific research. For example, people who worry that the new field of genomics could revive eugenics and fear for its impact on the most vulnerable members of our society could work to strengthen human rights legislation and ensure that any genetic advances are available to all segments of society, not just the wealthy. People who worry about the links between intelligence markers, such as IQ test scores, and life outcomes could support policies and technology that make society more accommodating for people with lower intelligence. For instance, state bureaucracies could make it simpler for people to navigate the red tape if they want to claim benefits or get access to affordable housing.

One final note: though I see Gould as the ultimate example of bias in the history of intelligence research, I am not exempt from my own biases. This is why in my article about Gould’s discussion of the Army Beta in The Mismeasure of Man my coauthors and I are completely transparent. We invite readers to check our interpretation of the primary sources (heavily referenced throughout the article) we relied upon to research the Army Beta. We also administered the test to a modern sample to examine whether it functioned like other intelligence tests, and we pre-registered our hypotheses and expectations and uploaded our data to a public repository. We believe that minimizing bias is best accomplished through transparency in data collection and analysis, rather than spurious claims of “objectivity” or intellectual courage.

Russell T. Warne is an associate professor of psychology at Utah Valley University. He conducts research on advanced academic programs, human intelligence, and methodology. Follow him at @russwarne.