recent

Twitter's Micro-Slavery

The inherent instability of slavery, fear, and dependence necessitate a collapse and reckoning eventually.

This is a response to “Who Controls the Platform?“—a multi-part Quillette series authored by social-media insiders. Submissions related to this series may be directed to [email protected]

In his new book Zucked: Waking Up to the Facebook Catastrophe, tech investor Roger McNamee writes:

“Lizard brain” emotions such as fear and anger produce a more uniform reaction and are more viral in a mass audience. When users are riled up, they consume and share more content. Dispassionate users have relatively little value on Facebook, which does everything in its power to activate the lizard brain. Facebook has used surveillance to build giant profiles of every user and provides each user with a customized Truman Show, similar to the Jim Carrey film about a person who lives his entire life as the star of his own television show. It starts out giving users “what they want,” but the algorithms are trained to nudge user attention in directions that Facebook wants. The algorithms choose posts calculated to press emotional buttons because scaring users or pissing them off increases time on site. Facebook calls it engagement, but the goal is behavior modification that makes advertising more valuable.

The term micro-slavery might provoke some readers to claim an improper and provocative metaphor. On closer examination, the metaphor unequivocally justifies itself. Public health campaigners and medical researchers have long equated the ravages, cruelty, and exploitation of narcotics addiction to chemical slavery. A virtually identical mechanism unfolds in a brain using Facebook or Twitter. Researchers of social media both in the Academy and in Silicon Valley have apprehended for a long time that social media prey on the dopamine rewards system of the brain. Some have used this knowledge to exploit users; others have used it to warn the public of a digital narcotic epidemic. The frisson of delightfully outraged purpose that courses through a user’s nerves as he reads or responds to a post arises from the same brain system that rewards a human being for consuming a healthy meal or organizing his sock drawer. The Hollywood actors who have done mighty work to support the Bolivian cocaine trade in the past can’t put Twitter down now, and that’s no accident.

Digital abolitionists grow more and more strident and numerous these days. Many—including early Facebook investor McNamee—hail from inside Silicon Valley. A raft of articles over the last few years have documented the wave of Silicon Valley techno-elites who, like savvy drug cartel bosses, forbid their own children from using the devices and social media platforms they build, while they encourage their employees to spend frequent periods “unplugged.” They know social media and mobile devices create users, and some have been brave enough to lobby the public for a shift in consciousness.

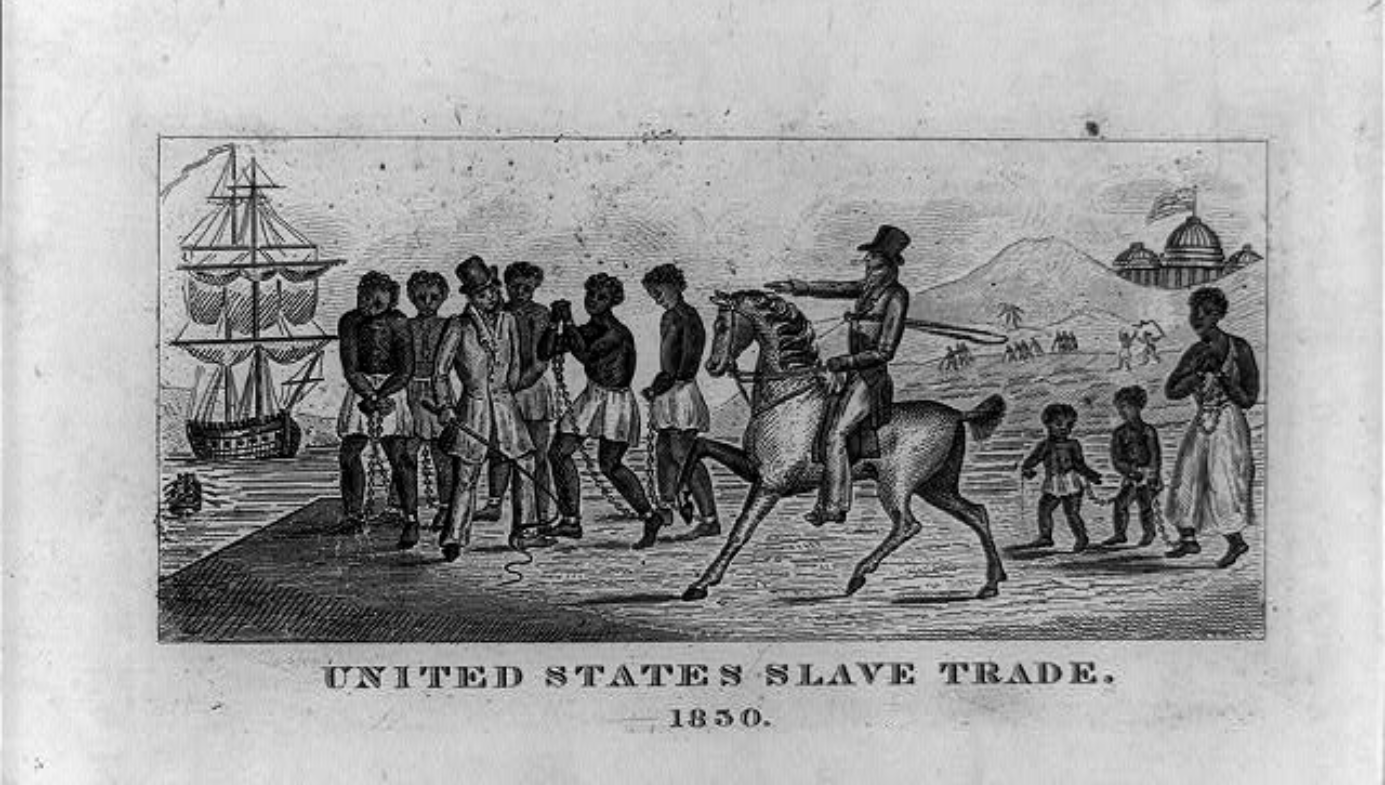

The slave reaps no substantial or real-world payment for his labor. Chemical slaves to drugs get nothing but misery and poverty in the end. Social media users subsist in an analogous trap, subtle and harder to spot. When it comes to social media, 99.9 percent of users will never see any substantial return on what stacks up to be an enormous longterm investment of time. Users will experience some fleeting stimulant sensations and a smattering of poorly organized—or incorrect—information. “I find out what’s happening on Twitter!” or “I get to promote myself on Twitter!” amounts to self-delusion on par with the vile Antebellum plantation saw that “Slaves get paid in the satisfaction of a hard day’s work and some are even taught how to read!” Such apologetics leverage false but presentable ends to cover horribly exploitive means—means the real ends of which are too embarrassing to admit. The average Twitter user might make the odd connection or get some attention for his business on Twitter, if he keeps at it day after day. In contrast, Jack Dorsey always gets paid handsomely for the user’s time on-site month after month by advertisers. The users work the platform with their attention, and Master Jack goes home with the check.

Unless already famous, the chances of reaping substantial reward from Twitter—such as income or significant growth of attention from others—roughly equal the chances of winning the lottery. And like the lottery, millions of average users chip in and hope, while just a few luck out and get a payout. Those few average users who get a mediocre reward—and even fewer who get famous with a lucky tweet or some such—keep the millions of average users coming back to try their luck every day. The little blue bird runs on the principle of the one-armed bandit and Powerball.

Virtually all users end up losing in the long-term. Most lose hours and hours scrolling through quips and posting burns, sifting through nonsense to find the odd bit of useful information, but mostly for distraction. Like their casino cousins cursed by fate with a gambling addiction, an unlucky minority of Twitter users lose everything on the platform without meaning to. A particularly ill-considered tweet brings down on their heads digital lynching, infamy, disgrace, loss of employment, loss of a spouse, libel lawsuits, and in some countries, criminal indictment for hate speech or threatening behavior. Uncounted thousands of users have operated their mobile devices under the influence of Twitter on the information superhighway, only to wind up with a digital DUI or in an online 25-car pileup.

Brain researchers and those with unusual common sense have noticed that Twitter produces much the same effect on good judgement as drugs or a gambling compulsion. To watch full-grown adults turn into excrement-flinging six-year-olds, put on a hazmat suit and open up any hashtag. There, responsible men and women—including those with awesome educations and much to lose—deploy grade-school sarcasm, slander, baiting, slurs, impudence, mixed metaphors, and threats toward … strangers. The spectacularly gifted and high-IQ billionaire Elon Musk recently called a stranger on Twitter a “pedophile.” Musk will soon make that “pedophile” a moderately rich man. A handful of celebrities who leapt on Twitter to dog-pile Nick Sandmann—the MAGA-hatted 16-year-old whose smirk reported round the world—probably will not get off so easy. Sandmann soon may face the agonizing decision of how to divide his time between the former mansions of Kathy Griffin, Jim Carrey, and Bill Maher. A few wily and stable celebrities navigate the emotional maelstrom of Twitter and reliably manipulate it to their advantage, like pushers able to resist the “product” of their business. Most other famous users wind up offering shamefaced mea culpas for their Twitter transgressions, in the spirit of Mel Gibson after his drunken anti-Semitic Malibu highway rant years ago.

Many will argue that Twitter users volunteer to participate. Of course they do. The party-goer who tries his first bump of blow volunteers to participate. Many smart and otherwise savvy African warriors probably could not resist the temptation to “Come aboard and check out my big Dutch canoe!” Such casuistry ignores the social pressures and ignorance of unfamiliar dangers at play.

Strictly speaking, slaves from Greek and Roman antiquity to the American colonies didn’t have to do as they were told, either. They could have refused to work—period. They just had to make peace with the pain and physical nonexistence that might follow if all the other slaves failed to follow suit and render an evil system untenable. Most of the time, only a few Spartacus-like souls will take such a risk. Human beings generally prefer even an oppressed existence to acute pain and nonexistence, rising up only occasionally. Ask any teenager for the score today: he who drops out of social media and limits himself to the nutritious Real World risks social nonexistence and psychic pain—no friends, no dating prospects, no idea what’s going on. Professional adults find themselves pulled into a treadmill dilemma, too. Anyone whose work or social life touches the information economy in any way feels he must participate enthusiastically on social media or risk falling behind in his profession, even if he hates Twitter and wants to take a shower after touching it. He must toil part-time in the Twitter micro-slave economy according to that economy’s uncompromising rules…or risk shelving with the Amish.

Ancient slaves had one advantage over today’s Twitter micro-slaves: they were neither in ignorance nor confusion about their slavery. They could put their hands on their chains. Most Twitter users do not apprehend the extent of their micro-exploitation or neurological confinement. The confusion evolves from a brilliant twist to micro-slavery that drug slingers pioneered and social media platforms perfected: chain up the mind, not the whole body. If you chain up a man’s body, you must house him, feed him, and guard him every minute of every day. That’s a lot of overhead, and terribly inefficient. Chemical brain-chains make a man feed and house himself, then toil part-time for Master Jack with little supervision or correction. The occasional “Violation of Community User Guidelines” lashing cuts the backchat and puts the fear of digital nonexistence into most wayward users.

A strung-out user must grasp his brain-chains before he can throw them off. That’s just the first step on a tough road. Any recovering drug or social media addict will explain there’s a categorical difference between spending a week sawing through an iron fetter and slogging through the agony of chemical withdrawal and rehab to escape back into the free world. Even after apprehending his brain-chains and finding the will to break them, the would-be Twitter runaway won’t possess the confidence to follow through and reclaim his peace of mind. Other users and Master Jack have inculcated in him the belief that his chains are a modern social survival tool, without which he supposedly becomes a Neanderthal who cannot talk to his friends, land employment, nor—in the case of Twitter’s kissing cousin the dating apps—find sexual release or a spouse.

If the reader hasn’t noticed, all roads lead back to fear. Fear of missing out, fear of scorn and loneliness, fear of painful withdrawal, fear of saying the wrong thing, fear of being understood the wrong way, fear that others will have their say on Twitter without someone to correct their immoral use of data and benighted views. God forbid a stranger posts 280 characters on the Internet that goes unchallenged and causes democracy to perish.

Human beings do their nastiest, cruelest, foulest, stupidest work hyped up on fear and its distillates. No wonder America’s political enemies find Twitter such a gift: fear makes Americans turn on one another. Twitter runs on angry fear, and it stinks of the stuff, inside and out. In Judeo-Christian tradition, the forces of evil were embodied as The Accuser (Aramaic: satana). Today, Twitter stands as the premier destination for anyone with a particular accusation, or just an accusatory grudge against his society and fellow man. On Twitter the jealous, resentful, cruel, bored, cowardly, oversensitive, manipulative, suggestible, destructive, and mentally ill find their anti-paradise, a rich Valley of Hinnom in which to whip up or join in fear-juiced lynch mobs, so they can all get their collective fix watching some unfortunate burn. Those who used to pack round the executioner’s stake now just reach into their pockets and tap the little blue bird. Twitter is the epitome of sadness and banality, a virtual prison packed with inmates abusing one another to display dominance and ease their jones.

Some will argue these analogues and concerns about Twitter world are overstretched and alarmist. Perhaps—but alarm isn’t always alarmist. Most people have either seen or heard tell of appalling outcomes connected to social media, particularly among the young. Pick your metaphor: micro-slavery, drug addiction, slot machines, the lottery, child exploitation, torture lust, prison…there is nothing good here. Denialists who retort, “Ahcktually…there are good parts to Twitter” bring to mind optimists of old who opined: “Burning that supposed witch wasn’t all bad. I got to warm my hands!”

The inherent instability of slavery, fear, and dependence necessitate a collapse and reckoning eventually. The center cannot hold. Digital micro-slavery is no exception. All that remains to determine is time and the final cost: how much micro-tragedy and micro-nastiness will it take before a moiety of users in the West find the Spartacus inside and tell Tribune Jack Dorsey to pound sand and find his labor elsewhere?

Alec Cameron Orrell is an accomplished sophist and poor financial prognosticator living in Los Angeles. He is not on social media.