Culture Wars

How An Anonymous Accusation Derailed My Life

#MeToo was an expression of solidarity but there is no solidarity for the accused.

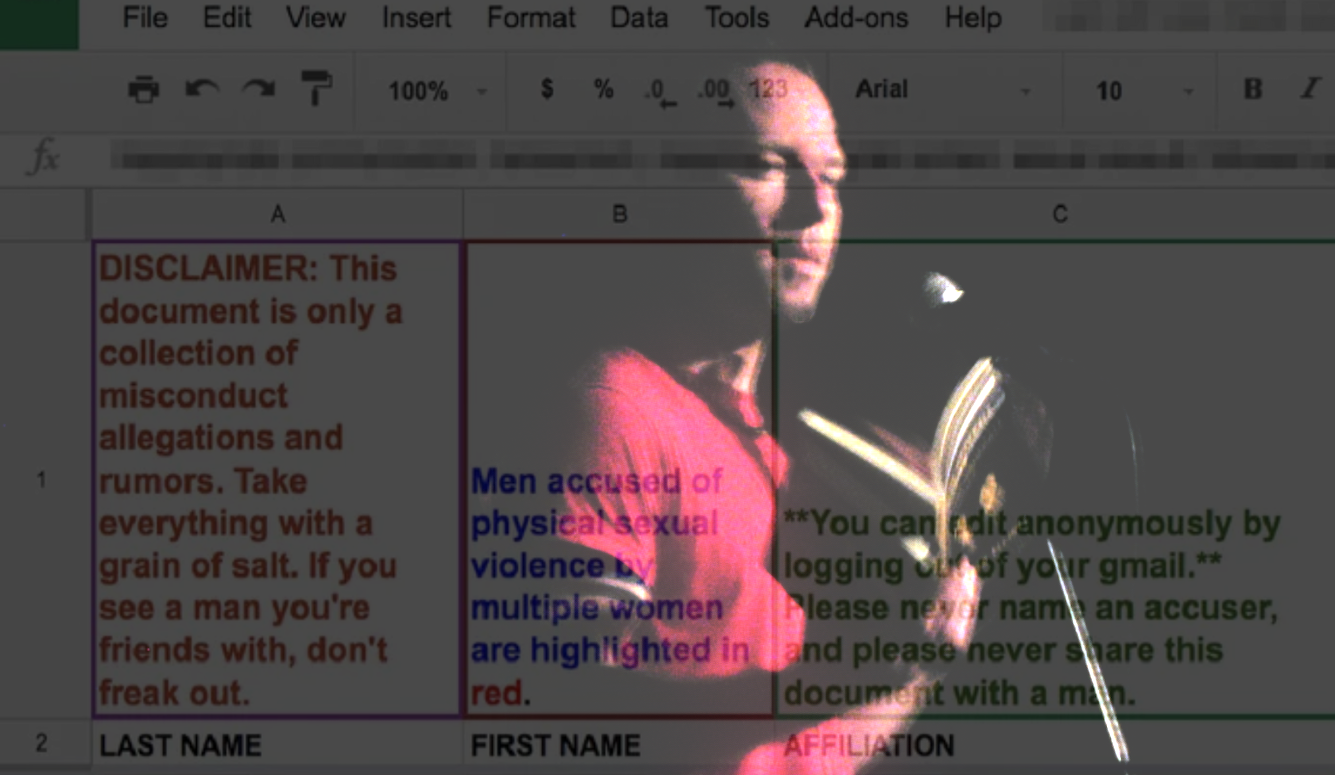

In early October, 2017, following the emergence of the Harvey Weinstein allegations, a writer and activist living in Brooklyn named Moira Donegan created a Google Doc entitled “Shitty Media Men.” She sent it to female friends working in media and encouraged them to add to it and forward it on. The idea was to spread the word about predatory men in the business so that women would be forewarned. Anyone with access to the link could edit and add to the list. At the top of the spreadsheet were the following instructions: “Log out of gmail in order to edit anonymously, never name an accuser, never share the document with any men.” In the first column was this disclaimer: “This document is only a collection of misconduct allegations and rumors. Take everything with a grain of salt.” Nobody did.

The list had only been live for 12 hours when word reached Donegan that Buzzfeed were preparing to publish a story about it. She immediately closed it down. By that time, there were already 74 entries. The Buzzfeed article ran the following day. Other media outlets soon followed up on the story and, shortly thereafter, the list was weaponized by right-wing blogger and conspiracy theorist Mike Cernovich. My entry reads: “Rape accusations, sexual harassment, coercion, unsolicited invitations to his apartment, a dude who snuck into Binders???”

I was shocked to find myself accused of rape. I don’t like intercourse, I don’t like penetrating people with objects, and I don’t like receiving oral sex. My entire sexuality is wrapped up in BDSM. Cross-dressing, bondage, masochism. I’m always the bottom. I’ve been in long romantic relationships with women without ever seeing them naked. Almost every time I’ve had intercourse during the past 10 years, it has been in the context of dominance/submission, often without my consent, and usually while I’m tied up or in a straitjacket and hood. I’ve never had sex with anyone who works in media.

I am not seeking to come out about my sexuality as a means of creating a diversion, as Kevin Spacey appeared to do when he was accused of sexual misconduct. I’ve always been open about my sexuality, and I have even written entire books on the topic. I’ve never raped anybody. I would even go one step further: There is no one in the world who believes that I raped them. Whoever added me to Donegan’s list, it was not someone with whom I’ve had sex.

Even though I was living in Los Angeles at the time, I found out that I was on the list immediately. It didn’t take much effort to find a copy; although the list was closed, it had been downloaded and was circulating freely on Reddit and WordPress. It was mentioned in an opening monologue by Samantha Bee, it was the basis of an episode of The Good Fight on CBS, and stories were being published about it in The New Yorker, Slate and The New York Times. Even so, most people didn’t bother to look at the list itself, and so didn’t know who was actually named on it. At the same time, many people did.

A few months after the list became public, an editor friend called me. The New Yorker had fired Ryan Lizza, who had been named, so the list was in the news again and my friend had looked it up. Then my sister, who works in the medical industry in Chicago, contacted me. Her friend had brought it up casually at dinner and I had to tell my sister that I hadn’t raped anyone. “I believe you,” she said.

Graywolf Press published a collection of my essays in November 2017. The pre-publication reviews had been positive but the book was greeted with silence. It’s impossible to know how many publications would have covered the book had my name not been on that list. At least a few cancelled their planned coverage. The Paris Review decided not to run an interview they had already completed with me for their web site. I was disinvited from several events, including a panel at the Los Angeles Festival of Books. Someone even called a bookstore in New York where I was scheduled to do a reading and urged them to cancel their event.

Similar lists were started in the advertising industry, fashion world, Canadian literature, and, of course, academia. Every time a new list appeared, there was a new round of stories mentioning the original list. This month, almost a year later, the Shitty Media Men List is mentioned in dozens of articles written about Leslie Moonves as he leaves CBS under a cloud of accusations.

I wondered if it would be possible for me to work with someone who didn’t know about the rape accusation. In Hollywood, the answer seemed to be yes. People there were only vaguely aware of the list and very few of them had seen it. Nevertheless, if I sold a pilot I’d written, or enjoyed any other kind of success, the company involved would almost certainly be made aware of the allegations quickly. If somebody was prepared to make the effort to call a bookstore to try to prevent me from reading to 25 people in Brooklyn, what chance did I have of flying under the radar after a post in Deadline?

Then my television agent stopped returning my calls. Was this just business as usual, or had she found out about the list? I didn’t know. If she did know about the list, she certainly wouldn’t be sending me to any meetings. Hollywood doesn’t care if you’re innocent or guilty; they just don’t want to be anywhere near that kind of controversy. Friends who knew I had been named stopped inviting me out. I started to get depressed, because I was walking around with this awful secret. I’d look someone in the eye and I wouldn’t know what they knew about me. I couldn’t talk about what was happening without revealing that I had been accused of rape. For several months I didn’t leave the house. I started taking drugs again and tried to stop thinking about it as my savings dwindled. It seemed like an impossible riddle.

Being accused of sexual misconduct is extremely alienating. #MeToo was an expression of solidarity but there is no solidarity for the accused. We don’t talk to one another. We assume that if someone else has been accused, there must be a good reason. We’re afraid of guilt by association. We don’t want to be noticed so we lower our voices. Most of us stop posting on social media and stick to ever-dwindling circles of friends.

Someone I know tweeted that it was ironic that supposedly liberal guys keep saying they believe women, but they don’t believe the women who accused them. I’ve wondered about the meaning of “believe women.“ I had assumed it was intended to encourage people to take accusations seriously. Certainly, sexual assault is enormously under-reported. But an anonymous accusation is problematic. What does “believe women“ mean when it isn’t even clear that an anonymous accuser is a woman? Anyone—male or female—with access to the list could have added my name while it was online.

* * *

Three or four months after the list was published, I wrote the first draft of this essay. I was trying to get sober and I was going to meetings. I wanted to build bridges and make amends, and I wanted to find a way to create space for my accuser to come forward. But I didn’t want to pretend to believe that I was guilty of something if I didn’t actually believe it. Fake apologies don’t help anything: A fake apology is like sewing up a wound with garbage. Some of the apologies issued since the #MeToo movement began had been unconvincing. They read like statements made by a person trying to keep his job and salvage his reputation with an act of forced contrition. This has only made matters worse and further divided people.

In the first version of this essay, I tried to examine any possibly problematic erotic or romantic entanglements. I contacted ex-girlfriends, people I’d kissed, and people who had rejected me. I wrote about hanging out in the park with a volunteer from the web site I founded, The Rumpus, and laying my head in her lap. I wrote about a woman who thought I had cancelled an article about her book because she had rejected me (actually, it had been cancelled for violating rules about friends writing positive reviews of one another’s work). But, in the end, I realized that it’s simply impossible to respond to an anonymous accusation. You find yourself confessing to every sin you’ve ever committed, real or imagined. Meanwhile, your accuser doesn’t even have a name.

The truth is, all of us have wronged someone at some point. At least I knew the rape accusation was false. But, about the other charges, I wasn’t sure. My entry mentioned that I was “a dude who snuck into Binders???” It turns out Binders Full of Women was a Facebook group for female and gender non-comforming writers. I’d never heard of it and I still don’t know who added me. My list entry also specified “unsolicited invitations to his apartment.” Of course I had invited people to my apartment. And of course those invitations had been unsolicited—an invitation is, after all, an unsolicited offer. But they weren’t my employees. I haven’t employed many people in my lifetime. Nevertheless, maybe someone had felt that I had power over them and had exerted inappropriate pressure to get them to accept such an invitation. But who? And when? And under what circumstances? I had no idea. There’s a conversation to be had about appropriate behavior, and I would always prefer to make amends. But I don’t think it’s a good reason to accuse someone of misconduct on an anonymous list.

When the Shitty Media Men List was first released, nobody knew who had created it. Then, in the early months of 2018, it was announced Katie Roiphe was writing an article about the list for Harpers, and speculation was rife that she would name its creator. And so Moira Donegan outed herself to beat Roiphe to the punch. “The value of the spreadsheet,” she wrote, “was that it had no enforcement mechanisms: Without legal authority or professional power, it offered an impartial, rather than adversarial, tool to those who used it. It was intended specifically not to inflict consequences, not to be a weapon.”

A number of commentators have pointed out that most of the men named on the list have not faced any consequences. Christina Cauterici, writing for Slate, drew her readers’ attention to “the absence of definitive evidence that any wholly innocent men have as of yet been tarred or feathered.” But Moira’s statement is disingenuous and Cauterici’s article was intellectually dishonest. Just because you don’t know of any consequences, that doesn’t mean there haven’t been any.

Of course, the list was a weapon. It was a way of saying: do not associate with and do not hire these men. Freelancers named on the list could not have the benefit of a workplace investigation that might clear their name—they would just stop getting work. Their book sales would sink. They wouldn’t be able to teach classes, and they would stop receiving offers for speaking engagements. They’d lose relationships and opportunities and they’d have painful conversations with their families during which they’d have to tell their siblings, “I didn’t rape anyone.”

Someone told me I shouldn’t deny the accusations. They asked if I wanted to be on the wrong side of the issue. Someone else asked me if I believed in the #MeToo movement enough to take a bullet. Over the course of this year, I’ve come to believe that if a movement embraces anonymous lists and a presumption of guilt, it is already poisoned and not worth supporting. I support reporting harassment and abuse in pursuit of safer workplace environments, and I believe we should be supportive of those with the courage to come forward. But I don’t have common cause with people who believe innocent-until-proven-guilty is just a legal concept.

* * *

The original version of this essay was significantly more conciliatory. New York magazine agreed to run it. It would have been the perfect venue, since it was there that Moira Donegan’s essay justifying her creation of the list had appeared in January. I worked with the editor for a few weeks and then, just as I believed it was about to be published, they informed me that it wouldn’t run after all. It was then accepted by two senior editors at the Guardian, but the essay was spiked again, apparently after other editors revolted. I’ve never had an essay accepted somewhere and then rejected. Now it’s happened twice.

Through the editor at New York, I tried to contact Moira Donegan. I sent her a note asking if we could speak, at a place of her convenience, alone or in the presence of witnesses, either on or off the record—however she preferred. I wanted to ask her how I came to be on her list. Were there in fact two accusations that she had combined into “rape accusations”? Did she touch my entry as an editor, or even as a writer? Was she the one who highlighted my entry in red, one of 16 entries identified in this way to indicate supposed multiple accusations of rape or violent sexual assault? I did not receive a reply.

At which point, I decided not to publish the essay after all. I decided that I wouldn’t be able to handle the blowback. As I struggled with depression, I was seriously contemplating suicide (every first-hand account I’ve read of public shaming—and I’ve read more than my share—includes thoughts of suicide). Maybe, I thought, I could find work in a writer’s room for a television show and that would make things okay. But the chances that I could keep my inclusion on the list and the accusation of rape secret were, I decided, remote.

It wasn’t until almost a year after the list became public that I realized I wasn’t depressed anymore. I also realized that writing for television was not my life’s goal. I packed my things and moved to a cheaper city where I could work in a less public discipline. I would pursue writing for its own sake, just as I had before I started publishing books.

When Donegan acknowledged creating the list, she wrote that she knew it was unreliable but that it was meant to protect women. She tweeted (or retweeted) the claim that many of the men on the list were being found guilty. She acknowledged that the document was indeed vulnerable to false accusations and “sympathize(d) with the desire to be careful, even as all available information suggests that false allegations are rare.” (In fact, U.S. numbers suggest that at least 5% of rape allegations are false or baseless, a higher rate than other major crimes such as murder).

Of course, in some sense, Donegan didn’t have to worry, because no one is truly innocent. Even if you’re not guilty of the particular crime of which you stand accused, you’re likely to be guilty of something. It’s a Kafkaesque scenario. The accused can either refuse to engage, or try to maintain their specific innocence from a position of more general guilt. Either way, the trial is over before any defense can arrive.