Health

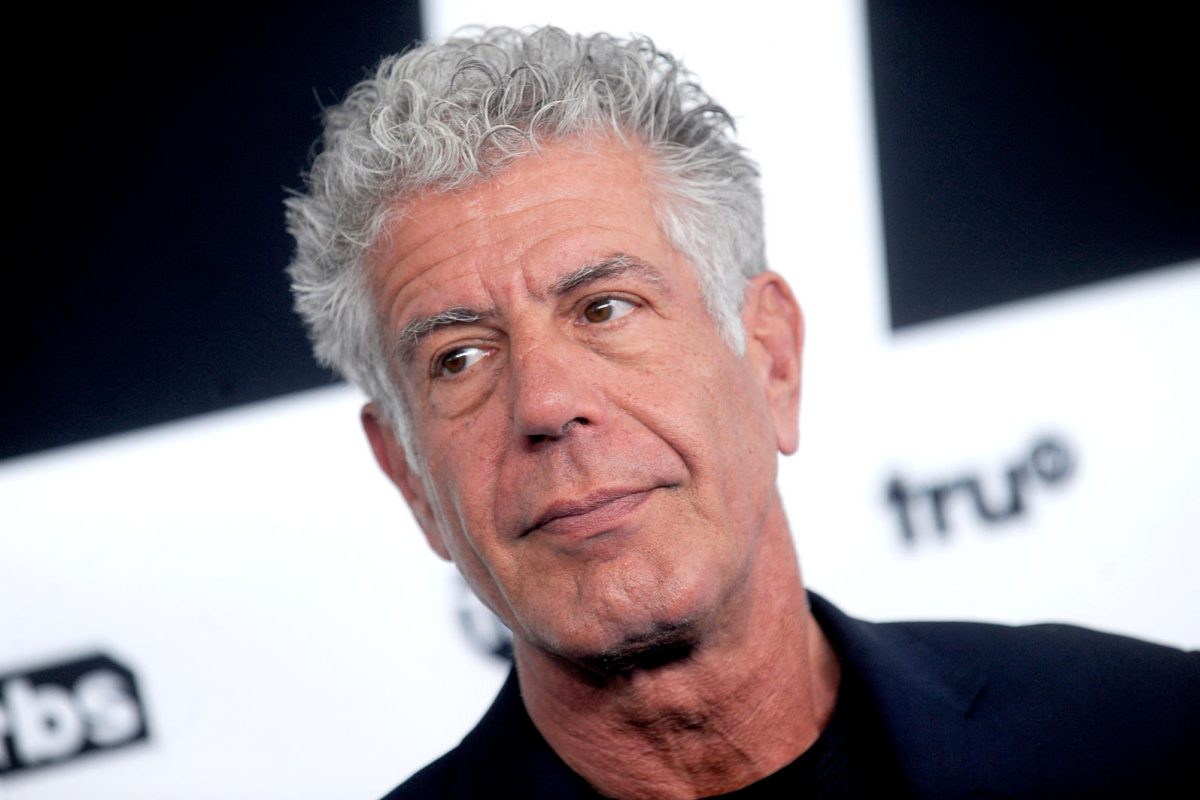

Anthony Bourdain vs. the Tyranny of Wellness

The cult of wellness commands: Thou shalt not contaminate the sacred body.

In Kitchen Confidential Anthony Bourdain wrote: “Your body is not a temple, it’s an amusement park. Enjoy the ride.” Bourdain encouraged us to travel to far-flung regions to experience other cultures through the communal act of eating. In Bourdain’s philosophy, food brings strangers together, so eating unfamiliar foods is a way to embrace other peoples and cultures and to welcome the unknown. Food—like life—is adventure and risk. Eating with others is choosing to live while we can.

Bourdain was at the height of popularity in an age defined by the sometimes perverse pursuit of health and longevity. Modern diet and health culture has become exactly what Roland Barthes predicted in a 1980 Playboy piece: its own religion and mythology. For perhaps the first time in history, fasting is more readily associated with the concept of “intermittent fasting” (which promotes autophagy, or cellular cleansing to increase lifespan) than with the idea of prayer. Put another way: we fast to cleanse our cells, not our souls.

Bourdain, on the other hand, represented a refreshing escape from the religiosity of the wellness movement, and from the burdensome responsibility it imposes. As Michelle Allison argued in her Atlantic essay “Eating Toward Immortality” last year, “If you are free to choose, you can be blamed for anything that happens to you: weight gain, illness, aging—in short, your share in the human condition.” With regard to diet culture, we are, as Sartre would say, “condemned to be free” to choose every morsel that passes our lips, and thus responsible for any disease or ill mood that befalls us.

The cult of wellness commands: Thou shalt not contaminate the sacred body. We are told to avoid what is ‘toxic’ and ingest only what is ‘clean,’ even as definitions of ‘clean’ continue to shift and vary. To stave off disease and aging, we must learn not only what to eat, but also how and when. We must eat at appropriate times of day, and in the right combinations and ratios, to ensure optimal circadian rhythms and the proper balance of gut bacteria, among other things. To regularly consider each of these factors is a full-time job, and one that is nearly incompatible with eating with other people. This is because eating is now less of a social bonding ritual than a solitary religious rite. In this current framework, food has the power to cleanse, purify, and redeem—and with that power comes an enormous capacity for error and a crushing accountability.

The Internet abounds with accounts of people who have used diet to cure themselves of every condition from OCD and psoriasis to depression and cancer. Although evidence is clear that nutrition is inherently medicinal, the current thinking has taken it a step further to suggest that diet represents a way to control for every possibility of disease, or even general unease. Barbara Ehrenreich describes this phenomenon in Natural Causes, citing public reactions to the deaths of David Bowie and Alan Rickman, who both died in early 2016 at the merely respectable age of 69 of an unspecified cancer. As Ehrenreich writes, “some readers complained that it is the responsibility of obituaries to reveal what kind of cancer. Ostensibly this information would help promote ‘awareness’.” To withhold this information is to put public health at risk. Rickman’s death might have taught us something about our own mortality if only we could know what type of cancer he had and what he ate every day (or better yet, what his mother ate when he was in utero). As Ehrenreich puts it, anyone who dies at an ‘untimely’ age has to undergo a “bio-moral autopsy.”

Another manifestation of the crass pursuit of health is the ‘Live to 100’ movement, in which the body is a battleground on which we fight disease with antioxidants, superfoods, positive thinking, and the like. If we consume the ‘right’ things and avoid the ‘wrong’ things (and it is never self-evident which is more crucial), then we can postpone death, or at the very least, die peacefully in a state of relative vibrancy. Centenarians and super-centenarians around the world are scrutinized in an attempt to identify their secrets. In this modern mythology, the hero is the person who manages to live to a hundred with all mental faculties intact and the ability to run a decent marathon, prolonging her own mortality by skirting the infinite number of things that can go awry.

One of the reasons I loved Bourdain—why so many people strongly identified with him—was that his apparently uncontrived posture was one of rebellion against the overwhelming responsibility imposed by modern diet and health culture. Bourdain’s stance in Kitchen Confidential might, for good reasons, sit uneasily with anyone who believes the body should be viewed as more than a playground. To live good lives, or even to function at all, we should be discriminating with what we consume. Or as Warren Buffett recently reminded young adults, “You only get one mind and one body. And it’s got to last a lifetime.” Yet, despite these reasonable objections, something within me rebels against a health culture that has developed its own mythological structure bordering on religious mania. Wellness culture says: pursue health and wholeness and you will be long-lived upon the earth; but it eliminates a fundamental question: to what end? Indeed, there will still be one.

Bourdain would say: focus on the people around the table, wherever on the planet that table is, and eat what you are damn well served. Savor the company of people whose lives and backgrounds are unimaginably different from yours. In short, prefer people to the pursuit of that otherworldly glow, the attempt to lengthen your telomeres, and the dubious ‘achievement’ of living to be 110.

This is one of the many reasons why Bourdain—and all that he stood for—was so appealing, and why, as CNN Executive Vice President Amy Entelis recently said, “his death still feels unreal.” The final season of Parts Unknownis about to air. When it ends, who or what will provide that much needed escape from the tyranny of wellness?