Social Media

Is It Time to Regulate Social Media?

We would not tolerate a phone company cutting off somebody’s service because of the words they used in their conversations.

In these increasingly polarised times, Facebook, Twitter, and Google have managed to attract disdain from both sides of the political spectrum. According to the progressive Left, social media is a lawless frontier where abusive trolls poison the atmosphere, racism and sexism are rampant, and various far-Right groups propagate fake news for their own nefarious purposes. On the Right, meanwhile, Facebook and Twitter are perceived to be safe spaces for terrorist recruiters and child pornographers, policed by intolerant Silicon Valley liberals who use secret algorithms and targeted censorship to suppress conservative thought. Establishment politicians on both sides investigating Russian influence in the 2016 election recently grilled Facebook and Twitter over the issue. Suddenly, everybody seems to agree that, unless and until state power brings these companies into line, social media will pose a threat to truth, morality, and even democracy itself.

Social media has certainly helped to transform the environment in which political discourse takes place. Conversations that might once have occurred in pubs or town hall meetings are now happening online. The anonymous Twitter account and the blog have replaced the soapbox as the preferred platform for political speeches and tirades. The public square, while still notionally ‘public’ in the sense of being broadly visible, is increasingly under the jurisdiction of private corporations whose primary concern is advertising revenue, not democratic transparency. The rules by which these online spaces are policed seem to be vague and arbitrarily enforced, with moderators often accused of censoring entirely lawful content in accordance with their own biases. Facebook in particular has also been hit by privacy scandals, with large numbers of young people turning their backs on the site as a result. The calls for government intervention are not impossible to understand.

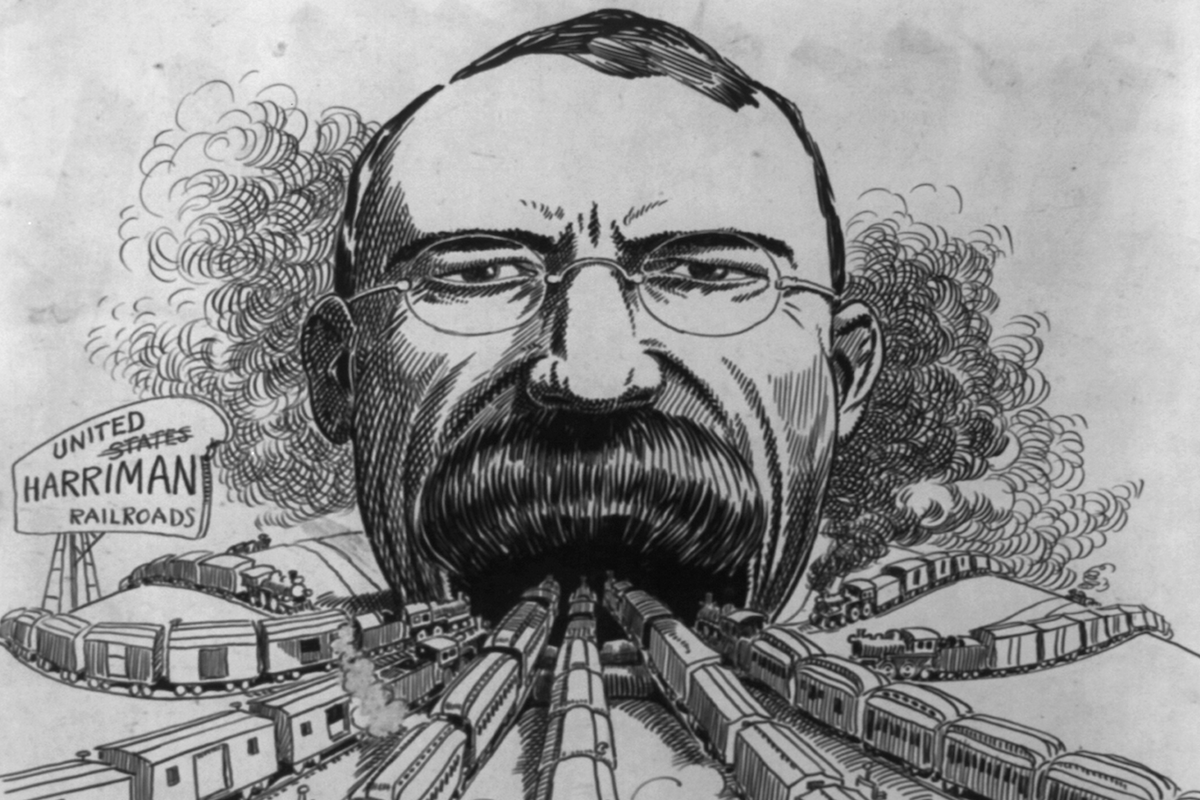

Demands for regulation are therefore appearing from all directions. The progressive Left, the establishment, and the populist Right are all now insisting that something must be done (presumably on the assumption that they, rather than their political opponents, will be the ones doing it). The proposals vary in their specifics. Some conservatives in the US, such as Fox News presenter Laura Ingraham, have suggested that Facebook and Twitter should be treated like public utilities, and regulated as a phone or gas supplier might be. Politicians in Europe, perhaps aware that they have less influence over American corporations, favour more targeted legislation that punishes platforms that fail to protect children or remove ‘hate speech’ in a timely fashion (an approach which has already been implemented in Germany). Even President Trump has started to echo the concerns about liberal bias raised by several prominent Republicans, although he has yet to propose any coherent solution beyond the usual angry tweets and some vague mutterings about antitrust action.

Of the various ways in which social media might be regulated, the openly partisan approach—in which Donald Trump barges into Silicon Valley, throws his weight around, and threatens companies with punitive legislation or antitrust action unless they start being nicer to conservatives—is probably the worst option. It might bring some satisfaction to hardcore Trump supporters who feel they have been mistreated, but such autocratic bullying is unlikely to have much lasting effect, and certainly does not establish any long-term protection for the freedom of users. It would also be a very short-sighted strategy, since Trump will not be in charge forever, and any actions he takes against the networks today may be repeated in the future by the next Democrat administration. If conservatives feel that social media is biased against them now, they will find it much worse once the naturally left-leaning companies are operating under the quasi-legal protection of a left-leaning government.

On the other hand, treating social media as a public utility is not entirely unappealing. Among certain demographics, online messaging has displaced the telephone and email as the preferred way to keep in touch with friends and family. We would not tolerate a phone company cutting off somebody’s service because of the words they used in their conversations, or because some anonymous and unaccountable mob denounced them as a Nazi. The argument that anyone who doesn’t like the behaviour of these corporations can simply use (or build) an alternative is rapidly losing its weight as the web giants proceed in lockstep to eradicate controversial content, and smaller sites that refuse to censor just get kicked off the internet altogether. Perhaps the time has come to recognise that the public square is now privately administered, and its participants need to be afforded the same First Amendment rights that protect them from censorship by the government?

A limited form of this type of regulation actually exists already. In the US, section 230 of the Communications Decency Act ensures that, in most situations, hosting providers are not responsible for unlawful speech posted by their users. Likewise, the safe harbor provision of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act offers immunity against copyright lawsuits, provided that sites comply with takedown requests from copyright holders. The Electronic Commerce Directive enforces a similar principle throughout the EU, with the additional requirement that networks must remain content-neutral in order to receive such protection (there is no such caveat in the US, despite what Ted Cruz may think). These laws don’t regulate web companies outright, but they provide a vital ‘mere conduit’ status, without which the hosting of user-generated content would be a legal minefield—imagine if Facebook executives could be dragged into court because someone, somewhere used the site to make a defamatory statement. It is therefore recognised that internet service providers are, to an extent, public utilities whose function is to transmit information without taking responsibility for its content.

Unfortunately, as vital as these legal protections are, they are already being rolled back. Section 230 has recently been weakened by FOSTA, a law which claims to protect the victims of online sex trafficking, but is drafted so broadly that several forums used by sex workers to exchange vital safety information have already been forced to shut down to avoid being prosecuted for “facilitating prostitution.” Legislators in the EU have changed direction even more dramatically with their plans to impose new copyright rules which will make platforms responsible for proactively monitoring user content for potentially infringing material. The NetzDG law in Germany, which has been criticised by everybody from Reporters Without Borders to the United Nations, gives social networks just 24 hours to remove illegal content (which, under German law, includes mere personal insults), providing a strong incentive for sites to quickly censor material rather than taking the time to evaluate its legality. With regard to online freedom, the world seems to have taken one step forward, then several steps back.

It is therefore clear that, whatever the problems with social media, we should be very cautious about asking the government to fix them. Even well-intentioned legislation may have undesirable effects. A law might be vague or excessively broad, such as FOSTA, or it may impose obligations that are impractical or even impossible to comply with, like the European demands for automated filtering of unlawful content. Conversely, legislation may be watered down with so many exemptions that it becomes almost useless, as is the case with Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights, which claims to protect freedom of speech but explicitly allows almost every category of censorship that has ever been implemented. Even an unambiguous, ostensibly freedom-promoting law risks creating more problems than it solves. If every user on every site has an inviolable right to speak freely, does this mean that focused discussion forums are no longer allowed to remove off-topic posts or ban disruptive users? Legal regulation is a blunt instrument, which is very likely to harm smaller sites far more than it affects Facebook and Twitter.

Furthermore, there is no particular reason to suppose that lawmakers would actually wish to increase, rather than reduce, online freedom in the first place. The recent Senate hearings have largely focused on establishment concerns such as Russian bots and drug dealers, rather than the overzealous censorship or violations of privacy which are affecting everyday users. One might argue that this is unsurprising given that it is the Senate Intelligence Committee conducting the hearings, but the fact remains that few, if any, mainstream politicians are publicly demanding an unrestricted right to speak freely on social media. Laws reflect the attitudes of the time, and sadly the prevailing attitude of our present time—at least amongst those who set the legislative agenda—is that speech is already too free, too dangerous, and in need of ever greater restrictions to protect society.

As some of these examples have shown, not all regulation of technology is necessarily a disaster. Mere conduit laws provide important protections which allow sites to serve user-generated content without incurring unmanageable legal risks. In theory, it should be possible to strengthen rules like these, relieving service providers of any obligation to proactively censor content, and discouraging (but not necessarily outlawing) ideological bias by granting additional immunities to social media companies that take a content-neutral approach to moderation. The problem is persuading today’s politicians to pass such laws, instead of taking the opportunity to crack down on indecency, hate speech, Russian collusion, or whatever contentious political issues they otherwise care about. Western society is becoming increasingly hostile to freedom of expression, with many political groups disagreeing only in the details of what needs to be banned. Unless we can find some way to reverse this trend, giving the government more control over the internet is likely to result in the censorious attitudes of today becoming enshrined in law for a generation or longer.