Top Stories

Taming the Lizard Brain

The history of consumerism can be seen be as the growing sophistication to tie our primitive instincts to consumption behaviours.

There is money to be made from stopping us from using our devices, but it might involve better regulation of our most primitive selves.

Apple’s controls to help us limit our phone usage is the clearest evidence yet that self-regulation of technology companies must include not just data privacy, but protections of our humanity.

Apple has included features on its new phones that turn off notifications overnight, during driving and expand parental protections. Google is implementing similar such controls.

In the wake of the Facebook and Cambridge Analytica data scandals, the so-called tech-lash is the ultimate wake up call. It’s never been more essential that the industry considers implications beyond the user experience in the race to further monetise our attention.

“If you don’t self-police, if you don’t preserve the trust of your user community, then you will get regulated. The downside with regulation is that government can’t keep up with the pace of technology,” says John Hennessy, the Chairman of Alphabet.

That erosion of trust stems from growing mental health effects linked to technology use, the scandals related to intrusions into personal data and the deleterious effects upon democracy from fragmentation into tribal bubbles.

The history of consumerism can be seen be as the growing sophistication to tie our primitive instincts to consumption behaviours. The father of public relations was a man called Edward Bernays, a nephew of Sigmund Freud. The advertising industry that emanated from that has been adept at exploiting our deepest insecurities around status, feeling loved or base fears. This is stated neatly by one of the influential figures of twentieth-century advertising, William Bernbach—

It took millions of years for man’s instincts to develop. It will take millions more for them to even vary. It is fashionable to talk about changing man. A communicator must be concerned with unchanging man, with his obsessive drive to survive, to be admired, to succeed, to love, to take care of his own.

The benefits of modern technology in democratising information and connecting humanity are extraordinary. The flip side is that our ability to further exploit our reptilian natures, the primitive part of our brain lurking underneath a sophisticated but fragile layer of rationality has never been greater. This is especially true online through the feedback loop of algorithms and human actors.

American venture capitalist Roger Mcnamee is a co-founder with other tech insiders for the Centre for Humane Technology. In a podast interview with the Financial Times, he says the rise of the smartphone represents the apex of delivering information in a continuum from the tabloid newspaper in the 1830s that appeal to our lizard brain, which is the primitive part attracted to instant reward.

Fatty food, internet pornography and illicit drugs all prosper from co-opting the same pleasure, neural pathways.

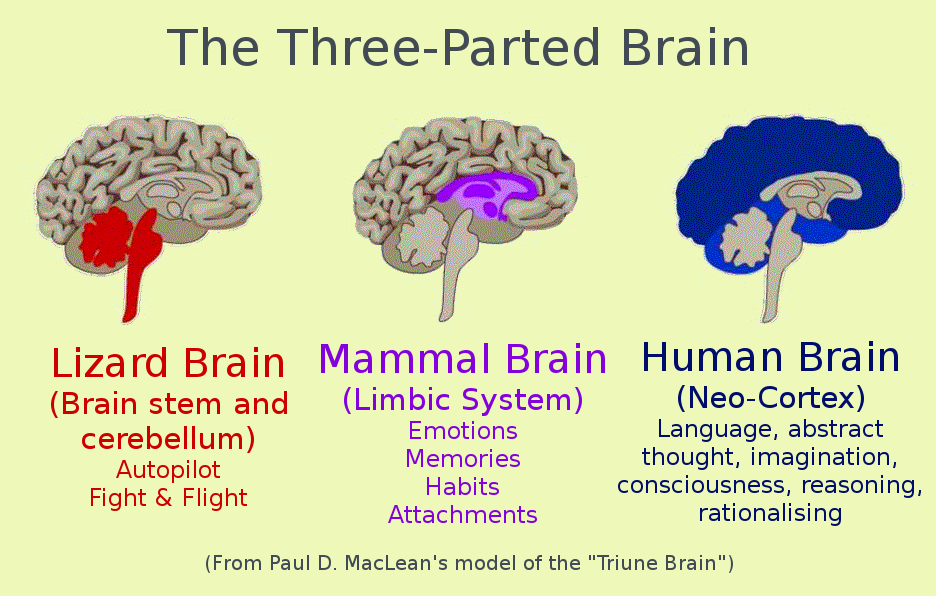

While modern neuroscientists consider the view simplistic, for decades the brain was seen structured as a triune where the bottom layer composed of the basal ganglia and the forebrain was seen as a throwback to reptiles.

The other layers include the emotional centres known as the limbic system and the areas of rationality known as the cortex, larger in humans than in any other primate. Renowned neuroscientist Paul Mclean who coined the term triune referred to the lizard brain as responsible for “species-typical behaviours” which arise in aggression, dominance, territoriality and ritual displays.

Exploiting our lizard brains makes advertising more effective. Beyond advertising, however, those who better manage impulse control function better in relationships, goal setting and occupational achievement. A significant contributor to social and income inequalities are the variations in psychological frailties.

Some of the personal traits that we might previously have called good character incorporating self-control and restraint are especially important in today’s novelty filled world. British philosopher Avner Offer writes in the Challenge of Affluence that such novelty has never been cheaper and more available. But he also warns that prosperity speeds the flow of this novelty and it is occurring in parallel to the decline of what he calls commitment devices, the scaffolding that families, communities and social stigma used to provide in moderating the ravages of such disruption.

Amidst this wider social upheaval, enter the smartphone. Mcnamee argues that before the smartphone there was always a degree of inconvenience in the delivery device of advertising for example which allowed a natural limitation of its negative impact. But no more.

Research around smartphones, especially among teens, illustrate that it is a factor in heightening social anxiety, magnifying bullying and decaying the ability to conduct face to face conversations.

Anxiety and depression are spiking in today’s teens in parallel with a delay in adult behaviours. Teenagers today drink less, have less sex, have less interest in obtaining their driver’s license and don’t want to leave the house as often.

This is outlined in Jean Twenge’s much-cited book, albeit with a long-winded title iGen: Why Today’s Super-Connected Kids Are Growing Up Less Rebellious, More Tolerant, Less Happy — and Completely Unprepared for Adulthood — and What That Means for the Rest of Us.

I should state here that I am not a firm believer in Twenge’s thesis that technology and smartphones are the major cause of mental health problems, especially in teens. This is also borne out in recent studies, one of best being this large sample of adolescents in the United Kingdom which showed no evidence of moderate digital screen use worsening mental health outcomes.

However, they can play a role in magnifying problems that have always existed, such as when bullying extends beyond the playground to crowds online or when problematic behaviours like gambling become accessible in the lounge room.

In my work, one of technology’s key negatives is how it normalises pathological behaviours. Whether you’re a paedophile, terrorist or self-harmer, you can find an online community that will help you belong and even consolidate your behaviour. I have patients who put up pictures of themselves self-harming to their online friends for immediate feedback and gratification.

But the heady mix of smartphones, algorithms and social media present infinite possibilities for co-opting our biological vulnerabilities. This represents a great challenge for those who believe that individuals left to their own devices are most likely to make rational choices.

Psychotherapist and Professor at MIT Sherry Turkle says in a media interview that “I feel that we have now created an environment that will distract us to distraction … email and social media allow us to give the press release version of ourselves … It’s an algorithmic view of life.”

It is now algorithmic abstraction that shapes our human interactions from social media to the transactions on rideshare platforms like Uber. There is a growing risk that in a broader sense that we are outsourcing some of the most human tasks like empathy to the algorithm.

A proportionate tech-lash is an appropriate reaction.

Figures like Turkle and Mcnamee argue that understanding our vulnerabilities represents the first step in modifying device design and placing limits on trends like micro-targeting, which can allow marketers to link products to temporary emotional states tied to social media posts. In doing so, the challenge will be to find an adjusted balance for the modern world between the rational, cortex elements of our brain and the most primitive, but powerful lizard base.

We are perhaps entering a unique phase in business history where those who inherit the Earth will be the companies that best prevent us from using their product.