Top

Rejecting Progress in the Name of 'Cultural Appropriation'

Historically, it has been the European openness not only to foreign goods, but also foreign ideas – those which work, those which enhance our physical and mental wellbeing – that has signalled the forward march of modernity.

Another week, another set of manufactured outrages. New absurdities have been discovered recently in the UK as the Labour politician, Dawn Butler, has criticised the TV chef, and self-appointed guardian of the nation’s sugar levels, Jamie Oliver, for ‘cultural appropriation.’ His crime? Launching a product called ‘Punchy Jerk Rice,’ which, according to Butler, is ‘appropriation from Jamaica’ and ‘needs to stop.’

Until fairly recently the availability of global cuisines was seen as one of the few marked triumphs of multiculturalism. The idea of curry being a ‘National Dish’ for the UK was, as late as 2015, widely celebrated by left-leaning publications such as The Guardian and The Independent. This week, these publications signalled the illiberal transformation of their thinking by joining Butler in condemning Oliver. One eagerly awaits manufactured outrage from the British Italian community when they discover that Mr Oliver has a chain of restaurants called ‘Jamie’s Italian’ while, shock and horror, not actually being Italian.

The very prospect of sudden outrage from once-respectable newspapers at an idea that has been perfectly normal for decades is an indicator that the modern left is fast becoming intellectually bankrupt. Having thoroughly deconstructed our postmodern world to ensure that things fall apart (and that the centre can no longer hold), now leading voices on the left seem to search for false and virtually impossible notions of ‘authenticity.’

The idea of ‘cultural appropriation’ is not only illiberal, it is spectacularly anti-progress (in the technological sense), anti-trade, and anti-global. With the exchange of goods and services across borders over centuries has come also the flow and exchange of words and ideas. The meticulous work of the great French Annales historian, Fernand Braudel, has traced the movement of crops, spices, meats, and other products across history and geography. When a good idea comes along – let us say, the knife and the fork – networks of trade ensure that not only goods and services, but also customs and habits (let us say, table manners) take root relatively quickly to change ‘the structures of everyday life,’ even if change in the longue durée takes time. Ergo, the popular rise of the knife and fork across Europe in the sixteenth century gave rise to table manners in the seventeenth century.

It is scarcely possible to find some aspect of British culture that is not in some way ‘cultural appropriation.’ Take, for example, that most British of dishes, the Chicken Vindaloo. Of course, many would reflexively point to the subcontinent of India as the origin of this dish. But scholars of food would know that the red dried chilli peppers integral to the vindaloo are not native to Asia at all, but to South America. Indeed, neither is another vital ingredient, vinegar, authentically Indian. Both chilis and vinegar were brought to the Goan region by Portuguese traders in the 16th century. Imagine a Goan Dawn Butler in 1605 lamenting the ‘cultural appropriation’ of South American and Portuguese products by the local Goan equivalent of Jamie Oliver. She would deny us the Vindaloo.

Let us take a very different example: the tradition of English poetry. What could be more British than the Shakespearean Sonnet? ‘Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day? / Thou art more lovely and more temperate.’ Yet, any student of literature knows that the sonnet was an Italian form invented in 1235 by an Italian lawyer called Giacomo da Lentini and then popularised in the fourteenth century by Francis Petrarch. During the reign of Henry VIII, Sir Thomas Wyatt travelled Europe widely meeting courtiers from every country. He learned of the Italian sonnet while at court, as well as verse forms from France and Spain, and started imitating them in his own writing. If there had been a Tudor Dawn Butler ready to press the king to chop off Wyatt’s head for his ‘cultural appropriation,’ then British culture would subsequently have lost out on, among other things, Shakespeare’s sonnets, Percy Bysshe Shelley’s “Ode to the West Wind” (Wyatt also popularised terza rima, the form of Dante’s Divine Comedy) and Lord Byron’s Don Juan (which is written in ottava rima, another form imported by Wyatt). Indeed, the very English language is a magpie language which has taken freely from French, Germanic languages, Italian, Latin, Greek and so on for centuries. The total number of the words in the English language currently stands at 171,476 according to the Oxford English Dictionary, a symbol of its willingness to accommodate foreign concepts, and a total triumph of ‘cultural appropriation.’

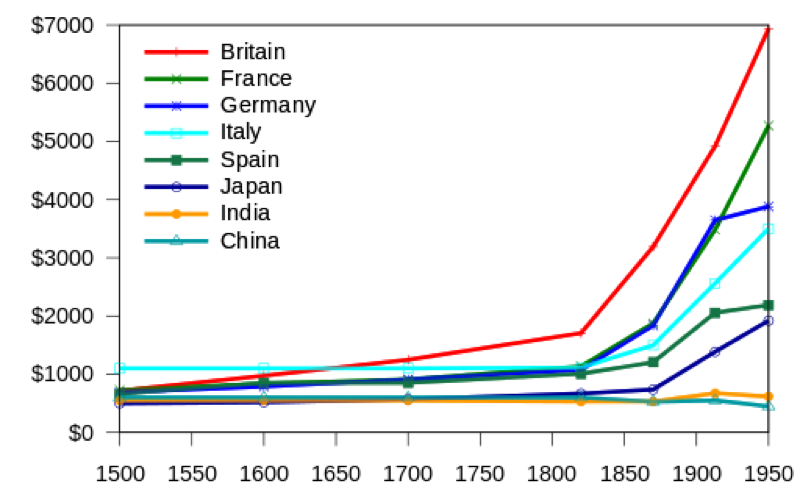

Historically, it has been the European openness not only to foreign goods, but also foreign ideas – those which work, those which enhance our physical and mental wellbeing – that has signalled the forward march of modernity. The rejection of foreign goods and ideas, commonly known as xenophobia, results in cultural isolationism. It has a poor historical record. As Ian Morris has shown, by every conceivable measure, the Chinese civilization stood neck-and-neck with their Western counterparts until about 1500. However, after this point, came the Great Divergence – a clear gap opened between Chinese and Western technological and economic development. As David Landes has argued, this divergence was primarily the result of Chinese isolationism – the refusal, from 1500 onwards, of foreign goods, and foreign ideas. This also helps to explain why in over four centuries of usage in Europe, the knife and fork failed to take root in China – whatever the relative merits of the chopstick.

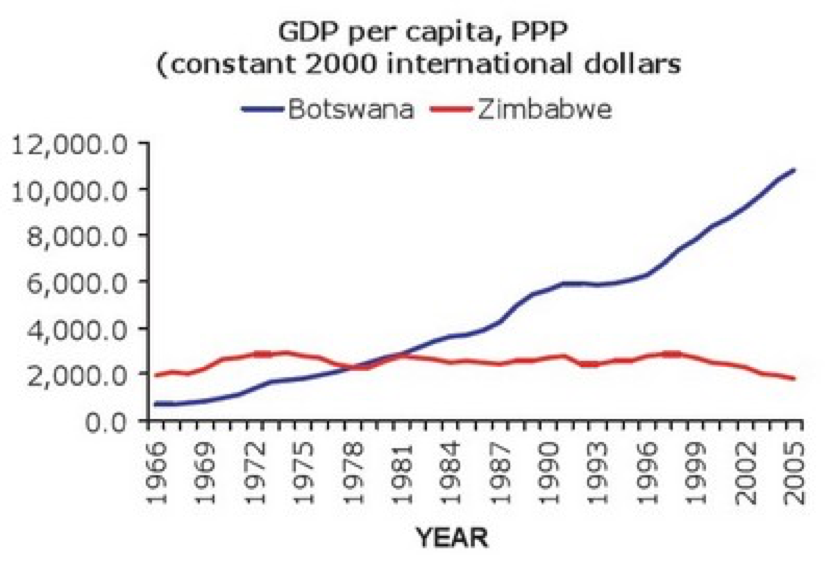

Similar effects can be seen whenever a nation decides to turn its back on other cultures. A tragic example from recent history has been Zimbabwe. For three decades, its Marxist dictator, Robert Mugabe, preached the total rejection of the ‘white man’ for whom he blamed all the ills of his country. His post-colonial rhetoric, so devastating for his people, was widely cheered at the time by the Western intellectual left who showered him with honorary doctorates and disingenuous assessments of his land reforms (funded by the London School of Economics, no less!). The result was cultural and economic isolation, and predictable disaster including hyperinflation and famine. Neighbouring Botswana during the same period adopted a policy of openness to business, a notion of inclusive and civic – as opposed to racial – nationhood based on the rule of law. Its GDP per capita growth has multiplied by over six times since 1980, while the Zimbabwean economy flatlined. Zimbabwe ranks 175th out of 180 countries on the Economic Freedom Index and relies on the fragile trade of agricultural crops. Meanwhile, Botswana ranks 34th out of 180 on the same Economic Freedom Index, and can boast of a booming diamond export market as well as impressive growth in foreigner visitor spending, which now accounts for 70.7% of Travel and Tourism’s contribution to Botswana’s Gross Domestic Product.

This is a tale of two nations: one closed to the world, and one open to it. The notion of “cultural appropriation” taken to extremes does not only cost economic and technological development, it can cost lives.

For all these reasons and more, no matter how fringe or absurd the voices of the far left sound in our intellectually bereft newspapers, and no matter how much Dawn Butler’s accusations of ‘cultural appropriation’ against Jamie Oliver make one roll one’s eyes – we are witnessing the birth of an incredibly dangerous, anti-modern, anti-progress, anti-trade, and above all anti-human way of thinking. I encourage everyone to be extremely vocal in condemning Dawn Butler, and in fighting fiercely to protect the principle of openness – to both goods and ideas – the very principle which has helped create prosperity, lifting millions upon millions of children out of abject poverty.