Security

Hashtags and Terror Narratives in Toronto

Any place can seem ‘no go’ to those who’ve never gone.

On April 15, 2013, hours after the Tsarnaev brothers set off explosives at the Boston Marathon, the #bostonstrong hashtag went viral on Twitter. A week later, at the first home Red Sox game following the tragedy, the Fenway Park public announcer declared, “We are one. We are strong. We are Boston. We are Boston strong.” Since then, the same meme has been adopted by numerous other cities in the wake of local tragedies—including my own, Toronto, which proclaimed itself #TorontoStrong following a deadly van attack that took 10 lives in April.

The idea that communities become stronger in the wake of mass murder is attractive. And sometimes, it’s even true—because outside threats stimulate a spirit of collective defiance and solidarity. But many acts of mass murder are perpetrated by mentally ill killers who have no political motive. In these cases, tragedies can actually widen fissures within society, because different factions co-opt the crime to advance their own agendas. Collective strength can exist only when citizens have a sense of common purpose.

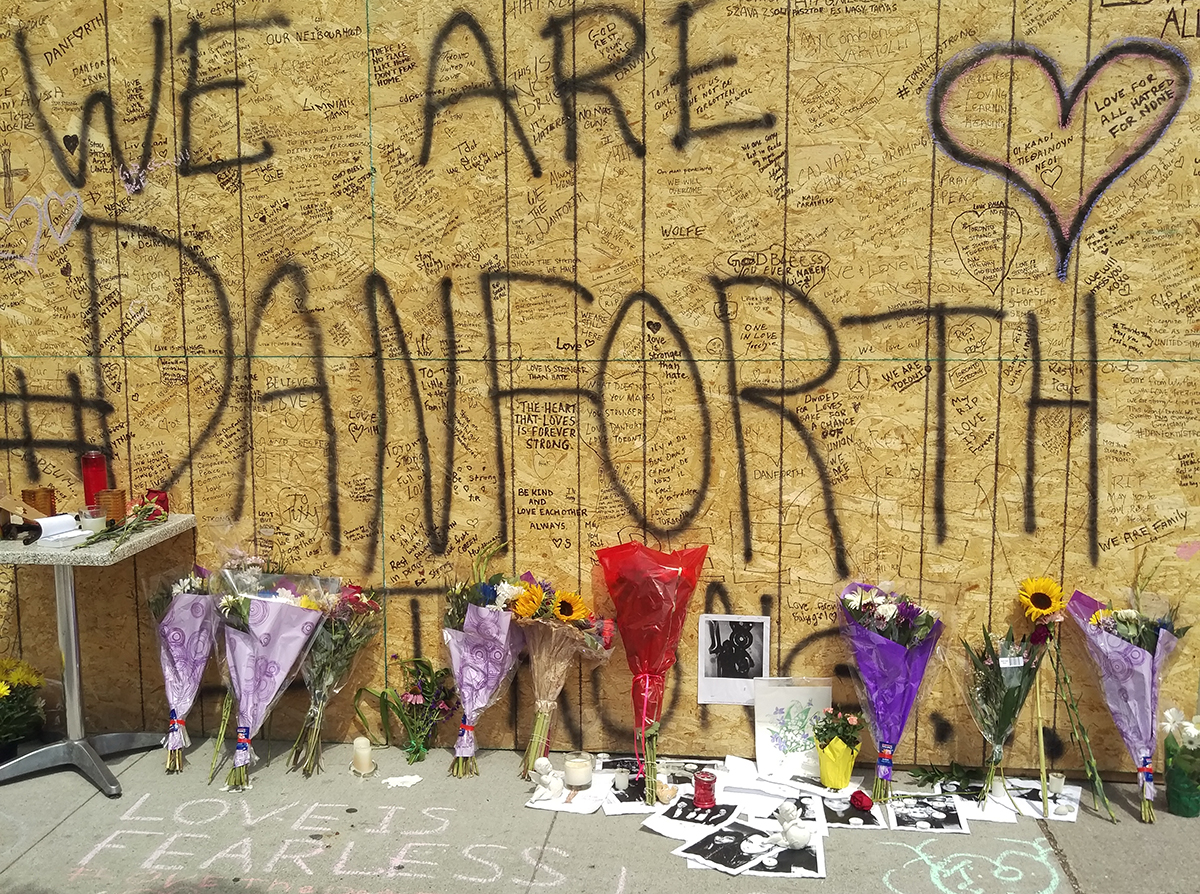

On Sunday, Toronto suffered another mass shooting, when a 29-year-old man named Faisal Hussain attacked a strip along Danforth Avenue in the city’s well-known Greektown neighbourhood, killing two and wounding 13. During the rampage, he moved from one side of the four-lane street to the other, seemingly targeting victims at random. Hussain isn’t known to have left any suicide note or manifesto. Nor is he known to have made any terroristic war cry or ululation before dying by his own hand.