Top Stories

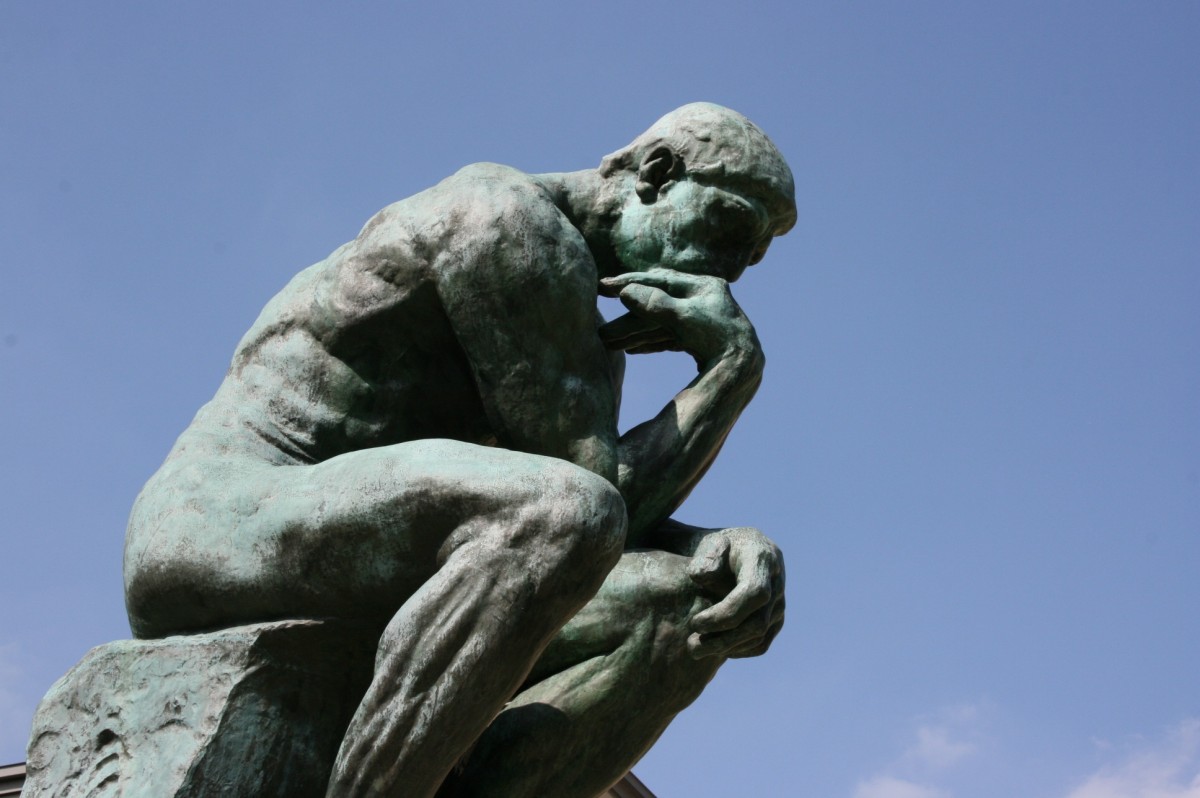

The Indispensable Study of Inescapable Matters

The subject of philosophy then is the study of indispensable ideas, regarding inescapable matters, at the root of man’s knowledge and values.

Philosophy is not merely practical; it is the most practical discipline of all. Indeed, philosophy is so practical that it is indispensable. To know why, it is necessary to know what philosophy is. In the Western tradition, philosophy is subdivided into five branches: metaphysics, epistemology, ethics, politics, and aesthetics.

Metaphysics is the starting point of any individual’s entire corpus of knowledge. Metaphysics begins with the axioms at the base of knowledge, and encompasses ideas pertaining to the basic nature of the world. These ideas include existence, consciousness, and their relation; entity, identity, attribute, change, and action; the nature of causality; and the nature and extent of free will. In short, metaphysics develops explicitly the basic concepts that are implicit in the very concept of knowledge.

Epistemology is the theory of knowledge, that is, the method of knowing. Epistemology addresses how to take the evidence of your senses and form concepts, statements, sequences of statements, and a corpus of knowledge that is organized, non-contradictory, readily applicable to new situations, and conducive to the discovery of new knowledge.

Ethics builds on metaphysics and epistemology—that is, on a base of knowledge and a method of knowing—to establish the starting point for knowing what to do with your life. Ethics enables you to identify your fundamental purpose and your means of achieving your purpose. Ethics identifies your fundamental values.

Politics is the application of ethics to the matter of using physical force against other individuals. Politics, therefore, deals with rights and with principles of government.

Aesthetics is the theory of art.

Philosophy is the most basic component of the entirety of mankind’s corpus of knowledge. All religions, for instance, have at their base an answer to the questions of metaphysics, epistemology, and ethics.

Why does philosophy, mankind’s most basic subject, include only the five branches identified above? Why are other fundamental subjects, such as physics—which at one time was considered part of philosophy—not fundamental enough to be included in philosophy? Part of the answer is that the five branches of philosophy are the only parts of a man’s corpus of knowledge that are so fundamental that they must not be delegated by one man to another.

You may rely on experts for answers in physics, mathematics, medicine, and so on. But you must not let anyone choose your religion (or atheism) for you, or choose your ideas regarding the basic nature of the world, or choose and develop for you your very method of knowing, or decide for you what is right or wrong, or decide for you how to choose and pursue your highest values. You do not delegate to others your basic ideas of politics; that is, you do not delegate your basic right to vote, or your basic judgment on the proper role of government. And if you are going to use physical force or sanction the use of physical force by government against other individuals, you had better have thought carefully about the matter. The power to vote can be and has sometimes been a weapon of mass destruction—or a requirement for prosperity.

You also do not delegate to others what you choose to love in art. You do not delegate to others the choice of which paintings to hang on your walls at home, what music to listen to in the car, what songs to sing with your family, or what movies to take your family to see.

Aesthetics depends directly on metaphysics and epistemology. An individual’s ideas on metaphysics and epistemology, whether these ideas are held explicitly or only implicitly, lead unavoidably to a basic evaluation about the world and man’s place in the world. For instance, one individual might evaluate the world as knowable to man and auspicious to human life—akin to being beautiful—whereas another individual might evaluate the world as inscrutable and leaving man doomed to misery. A work of art, to be effective, must project an imaginary world that is complete and coherent enough to imply a specific metaphysics and epistemology. It is the worldview of the artist that guides his creation of this imaginary world, and it is the worldview of the observer that shapes his response to this imaginary world.

It can be argued that there should be a sixth branch of philosophy: the study of romantic love. Virtually all the great philosophers have written about love. Like your response to art, your romantic love for another person is a response to the deepest values—the deepest philosophical values, the worldview—in the person you love and in yourself. As with the other branches of philosophy, you do not delegate to others your choice of romantic partner.

Another part of the answer to the question of why only these five or six branches of study constitute the subject of philosophy was identified by Ayn Rand in the title essay of her anthology, Philosophy: Who Needs It. Everyone has a philosophy, whether he wants to or not, whether he studies the subject or not. Everyone has a worldview and a way of drawing conclusions and a way of deciding what to do.

The subject of philosophy then is the study of indispensable ideas, regarding inescapable matters, at the root of man’s knowledge and values. Philosophy seeks to understand reality (metaphysics), knowledge (epistemology), goodness (ethics and politics), beauty (aesthetics), and love.

Many individuals acquire their philosophy—a philosophy they don’t even know they have, a philosophy they might not even agree with if they made it explicit in their mind—by passively accepting haphazard and contradictory pieces from half-identified feelings and from half-understood slogans of others. Without being aware of his philosophy, an individual might follow reason at work and emotions at home. Or he might be judgmental and selfish in his choice of a wife, and non-judgmental and altruistic in his advocacy of political policies.

Instead of acquiring your philosophy passively, you can develop your philosophy from a first-hand study of the great philosophers in history, followed by your own independent and systematic thought and judgment.

In studying philosophy, you will encounter philosophies that claim that metaphysics is fiction, knowledge is a subjective construction of individual minds or societies of minds, and free will is an illusion, and therefore that ethics is without a basis in fact or choice, beauty is naive, and love is blind and base. It is from such ideas, which have dominated modern philosophy—not to mention postmodern philosophy—since Hume and Kant, that the subject of philosophy has acquired a reputation for being impractical.

However, there is much more to studying philosophy than rescuing common sense from the assault by postmodernism. It is not enough to say, “Yes, there is reality,” “Yes, I have knowledge,” “Yes, there is good, beauty, and love, and these things are exalted.” You must be able to say, “This is reality, and here is what I know about it, and here is my validation of my method of knowing, and this is the good and how to achieve it, and here is how to create beauty and to love well.”

The importance of philosophy is a basis for the importance of history and literature. The thoughts, discoveries, and actions of history’s great men and women provide essential factual information from which to formulate and evaluate a philosophy. History shows the causal connection from thought to physical action to physical effect to further thought, action, and effect, from one individual to other individuals, from one period of time to the next.

The rational, this-worldly philosophy of Aristotle, rediscovered in Europe in the Middle Ages, led to the Renaissance, which led to the Enlightenment, which included the political writings of John Locke, which led to the political ideas of American revolutionaries, who put those ideas into action in the founding of the United States of America, which led to unprecedented prosperity.

By identifying the effects that great individuals have caused, history begins to reveal free will’s nature, scope, and degree of efficacy. Great literature takes this beginning established by history and builds from there. Whereas history shows what great individuals have done, literature shows what great individuals might choose to do.

Quoting Aristotle, “the difference between the historian and the poet is … that the one tells of things that have been and the other of such things as might be. Poetry, therefore, is a more philosophical and a higher thing than history, in that poetry tends rather to express the universal, history rather the particular fact.” [Poetics, Ch. 9, 1451b1–7, translation by James Hutton, 1982.] In this respect of expressing the universal, literature is a bridge from history to philosophy.

How, though, does literature express the universal, not only the particular fact? After all, the characters and events in a work of literature are as particular as the people and events in history.

Because literature is an art, an answer comes from aesthetics. As mentioned earlier, the artist must present enough particulars in an artwork to create an imaginary world with its own metaphysics and epistemology. But this imaginary world cannot possibly contain nearly as many particulars as does the real world. The author of fiction must select only those particulars that are conducive to being integrated conceptually into some theme. For example, every event in a plot might confront the main character with the ever-escalating consequences of having told a lie, along with the ever-escalating conflict of whether to perpetuate the lie. Given such a selection of particulars, the universal idea of honesty is readily grasped.

There is, then, a progression from the true stories of history to the created stories of literature to the fundamental, philosophical ideas that will guide the story of your life. And if you seek to build upon the greatness of those who lived before you, then you must study the history of the greatest individuals and cultures, the literature of the greatest writers, the works of the greatest philosophers.

Here then is why to study history, literature, and philosophy. These studies are the prerequisites for forming your own rational philosophy, which is the prerequisite for making the choices you must make for yourself.