Top Stories

Three Justifications for Liberalism

The fact that the complex history of liberalism is largely ignored by both its opponents and its alleged friends

In his 1988 article “Unger’s Philosophy: A Critical Legal Study” William B. Ewald criticized young leftwing up-and-comer Roberto Unger for his simplistic characterization of liberalism. Unger was one of the key founders of the critical legal studies movement, which philosophically oriented itself around his 1975 book Knowledge and Politics. In this seminal text, published when the author was only 28, Unger develops a systematic “total criticism” of liberal doctrines. He runs through broad interpretations of liberal psychology and liberal politics, arguing that these constitute a unified doctrine which “total criticism” largely knocks apart.

In his response, Ewald argued that while Unger was often creative and occasionally brilliant, he had badly mischaracterized liberalism. Far from being a unified doctrine, liberalism had historically been justified from a number of different philosophical perspectives. This made it far less vulnerable to “total criticism” than authors like Unger supposed. Indeed, it was quite hard to even pin down what liberalism was in a concrete sense. As Ewald eloquently put it:

Even at the level of concrete political discourse, the term (liberalism) is notoriously vague. Historically, the word dates from the years following the French Revolution; it designated a loose cluster of political principles—on the one hand, opposition to authoritarian forms of political organization (such as monarchy) and to the excessive power of the state; on the other hand, a concern for political liberties (freedom of speech and of religion), for democratic political institutions, for the separation of church and state, and for electoral reform. Even at this concrete level, these principles can come into conflict with one another, and liberalism soon split into branches, such as laissez-faire economic liberalism, movements for national self-determination, libertarianism, and New Deal liberalism—to mention only a few.

Today, this observation is worth directing against a large number of anti-liberals, who qua the young Unger tend to boil liberalism down to a fairly rote set of doctrines (I have also been guilty of this). Alain Badiou has spoken about the dangers of liberalism without developing an impressively robust criticism of its major thinkers. Slavoj Zizek has consistently spent more time arguing with various Leninists than substantially engaging with John Rawls, arguably the greatest political theorist of the twentieth century. Giorgio Agamben spends a considerable amount of time drawing on critics of liberalism from the far-Left and the far-Right, but far less actually looking at the works of its defenders. And so on.

Unfortunately, this deficiency is hardly just characteristic of the Left. As I highlighted in my recent Quillette article on Rawls, many rightwing exponents of liberalism also seem to be guilty of simplifying its doctrines to defend rather specific moral doctrines. The most common are self-identified classical liberals who call for a return to ‘meritocracy.’ These classical liberals see meritocracy a bulwark against the influence of postmodern identity politics. This is despite the fact that very few contemporary liberals of note believe one can justifiably defend meritocracy if one is sincerely committed to the principles of liberalism.

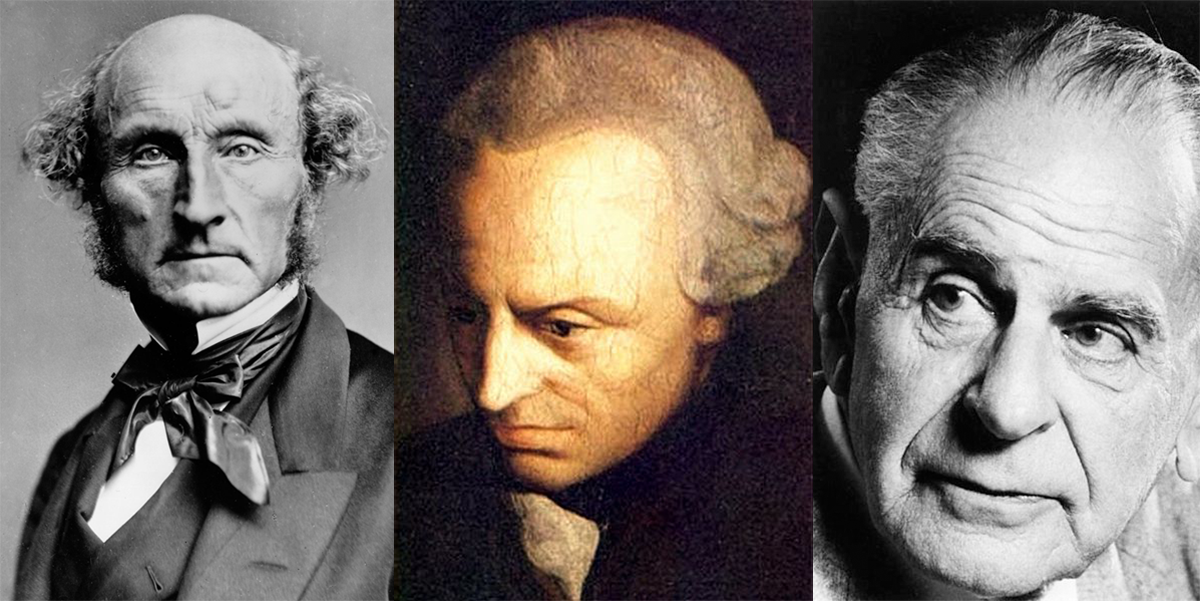

The fact that the complex history of liberalism is largely ignored by both its opponents and its alleged friends means this is as good a time as any to recapitulate some of the most compelling justifications for liberal doctrines. Historically, I believe there are three justificatory traditions that defend liberalism. The first is a consequentialist justification. The second is a justification appealing to freedom, and the dignity attributed to it. And the third justifies liberalism by appealing to epistemic and meta-ethical skepticism. I will discuss each in turn before concluding with an argument for why understanding this history is important.

It is important to recognize that this typology operates at a high level of idealization. Most of the thinkers I will reference appeal to some combination of arguments to justify liberal positions. Indeed, some more esoteric thinkers, notably the Kantian-consequentialist Hayek, deliberately attempt to combine the three types of arguments together into a consistent whole. But I have generally situated each thinker within the justificatory tradition with which they are most closely associated.

The Consequentialist Justification

The consequentialist justification for liberalism has a long history. Arguably, it can be traced back to proto- and early liberal thinkers such as Thomas Hobbes, who in the Leviathan famously argued that terms such as ‘good’ and ‘evil’ denoted little more than things which give us pleasure and those which give us pain. It was given its modern formulation in the work of figures like Adam Smith, J.S. Mill (in his purely utilitarian moments), and H.L.A. Hart.

Effectively, the consequentialist justification argues that liberalism is the most moral possible political system because it is the most conducive to promoting the greatest aggregate happiness of all. Consequentialist liberals argue for this position in many different ways.

Adam Smith claimed that restrictions on the pursuit of one’s desire, while potentially well meaning, would have the impact of decreasing incentives to produce and consume more commodities. This would have a negative impact on overall happiness, as societies would enjoy less wealth—here broadly understood—and individuals would have access to fewer goods and employment opportunities. To Smith, this suggested that the state should play a minimal role in interfering with the economic liberty of firms and individuals operating in the free market; though, notably, Smith did not think this argument justified not taxing the wealthy to make the poor better off. While less obviously connected to liberal politics than our next thinker, Smith’s claims have been profoundly influential in linking liberalism with respect for free markets.

Mill gave a different consequentialist justification for liberalism. He reacted against the strict act consequentialism of his predecessor, Jeremy Bentham, who enjoys a complex if influential position in the canon of liberal thinkers. In his book Utilitarianism, Mill argued that the happiness of individuals was the only intrinsic good, and that political society should be oriented around its maximization. But he resisted the Benthamite temptation to argue that this meant one should erect a rather strong and interventionist state that would always seek to maximize aggregate happiness regardless of the impact its policies might have on select individuals. In On Liberty, Mill argued that happiness must be understood as being about more than just pleasure and pain:

It is proper to state that I forego any advantage which could be derived to my argument from the idea of abstract right as a thing independent of utility. I regard utility as the ultimate appeal on all ethical questions; but it must be utility in the largest sense, grounded on the permanent interests of man as a progressive being.

As a “progressive being,” human beings longed for liberty since it was the most effective way to pursue their private vision of happiness. For Mill, this suggested that the liberal state, which allowed individuals very broad latitude to pursue happiness as they understood it, was the most moral from a consequentialist perspective. Mill was deeply skeptical of arguments for allowing a government, even one composed of the very wise, to control the lives of individuals in order to make people happier. By demanding all individuals pursue what the state thought would be conducive to happiness, the government would actually cripple their capacity to discover what actually brought them the most satisfaction. This would have a negative impact on the individuals at hand, and all those who might be inspired by them.

What unites the various consequentialist justifications is their claim that happiness is the end goal of human life, and that the aggregate welfare of all is the end of a just political system. Each thinker believed that a liberal state which allows individuals wide latitude to pursue happiness is the most conducive to the aggregate welfare of all, and is therefore the model to be adopted. This is a powerful justification for liberalism, but it is not without its critics. For some, the idea that liberal freedoms are justified because they are conducive to happiness ascribes them far too little value. These liberals argue for their position by claiming that the value of freedom itself, regardless of its association with happiness, is the key justification for liberalism.

The Justification from Freedom

A very different justification for liberalism emerged in continental Europe at the turn of the eighteenth century; it is perhaps the most intriguing and—to my mind—inspiring. Authors in this tradition regard consequentialism as too weak a defense of freedom. While it might be true, qua Smith and Mill, that the greatest happiness for the greatest number of people would be produced in a free liberal state, this makes respect for freedom contingent on empirical factors. What might happen if it turned out that a totalitarian state, such as the one theorized by Aldous Huxley in Brave New World, was more conducive to producing aggregate happiness? Wouldn’t the consequentialist feel compelled to abandon his support for liberalism? For liberals concerned with freedom as an ‘end in itself’ this was unacceptable. They argued that the justification for liberalism is freedom itself, regardless of whether freedom was conducive to happiness.

The most famous liberal thinkers in this tradition are Immanuel Kant and his many intellectual disciples such as John Rawls, Allen Wood, Martha Nussbaum, and so on. Each of these thinkers argued that ‘freedom’ is a good in itself. Often, this is connected to some account of human dignity, wherein individuals are seen as being fundamentally different to other objects in nature. All objects in the world can be impacted by other natural forces, and other animals can be motivated by pleasure and pain. But for these liberals, it is the fact that human beings alone can choose what to pursue, even to the extent of sacrificing their own lives for the sake of another, which gives us a moral dignity. As Kant put it in the Groundwork to the Metaphysics of Morals:

In the kingdom of ends everything has either a price or a dignity. What has a price can be replaced by something else as its equivalent; what on the other hand is raised above all price and therefore admits of no equivalent has a dignity.

What this means for liberals in this tradition is that individuals should never be understood as simply a ‘means’ to another end. This includes being treated as a means to the end of producing the greatest overall happiness. It is up to each person to decide what they will pursue in life, and a liberal society is justified because it largely allows and even enables them in these decisions.

Where controversies emerge in this liberal tradition is on the last point. Some proponents of freedom, notably Kant himself and Nozick, believe that the state should largely just allow individuals a great deal of freedom to pursue their own ends. By contrast, leftwing liberals in this tradition argue that the state should play a substantial role in enabling individuals to enjoy ever greater freedom in their pursuit of different life plans. Liberal critics like Rawls, Nussbaum, Dworkin, and others argue that the morally arbitrary limits placed on the individual’s freedom through lack of wealth and resources is a deep infringement on their dignity. To my mind, this debate is amongst the most interesting in modern liberalism.

The Justification from Skepticism

The third justification for liberalism draws on rather different arguments. These liberals claim that authors in the first and second justificatory traditions are far too confident in their assertions about obvious moral principles. Consequentialists take happiness to be the end goal of human life, while Kant and his disciples emphasize freedom. For skeptical liberals, both traditions are far too confident in asserting that there is a singular value which justifies liberalism. They argue that liberalism is justified precisely because we can never be certain what makes life worth living. Therefore, a good society is one that allows individuals to experiment with different ways of living.

Liberals in this tradition include Karl Popper and Isaiah Berlin. These authors are skeptical that one can justify a political system on the basis of a singular principle, such as maximizing happiness or freedom. For Popper, we should be deeply suspicious of arguments that justified moral claims purely on the basis of abstract principle. This, he argued, was highly unscientific and could potentially lead to dogmatic moral absolutism. Instead, the virtue of liberalism was its connection to the scientific method. Individuals were given a wide latitude to experiment with many different lifestyles and possibilities, and then determine through complex forms of judgment which of these seemed most conducive to their interests.

Berlin went even further. He argued that, since Plato, Western thinkers had been convinced that all moral values must align together. A virtuous individual would also be a free individual, a free society would also be an equal one, and so on. For Berlin this reasoning was highly flawed. He was skeptical that one could ever bring all worthwhile values into line, whether through reasoning or in practice. Instead, Berlin argued for a kind of “value pluralism” wherein there were many worthwhile ends one could pursue in life. Many were mutually exclusive. One could pursue a life of aesthetic excellence, but then would have to accept that writing Gravity’s Rainbow was unlikely to win you the same commercial success as writing 50 Shades of Grey. One could go into politics and impact civil society, so long as one recognized that this would entail dropping a firm commitment to principles and becoming willing to compromise with reality. And so on. The virtue of a liberal society is it did not judge between these different but valuable ends. It allowed individuals leeway to make up their own mind about which were worth pursuing.

Conclusion

Understanding the justifications for liberalism is integral to grasping broader debates in today’s society. Today, a caricature of liberalism is often attacked by the Left. Not to be left out, a caricature of liberalism is often defended by those on the Right. It is not clear to me which is worse. Indeed, as implied my most recent Quillette article on postmodern conservatism, I am deeply concerned that these pressures from both Left and Right will eventually make it impossible to have a sustained and rational debate about the clear virtues and defects of liberalism. As political argument is increasingly dominated by tense appeals to both skepticism and the authority of identity, it might be worth taking a hard look at what liberalism is, what we can still learn from it, and where we can improve upon it.