Centrism Debate

American Centrism Has Failed

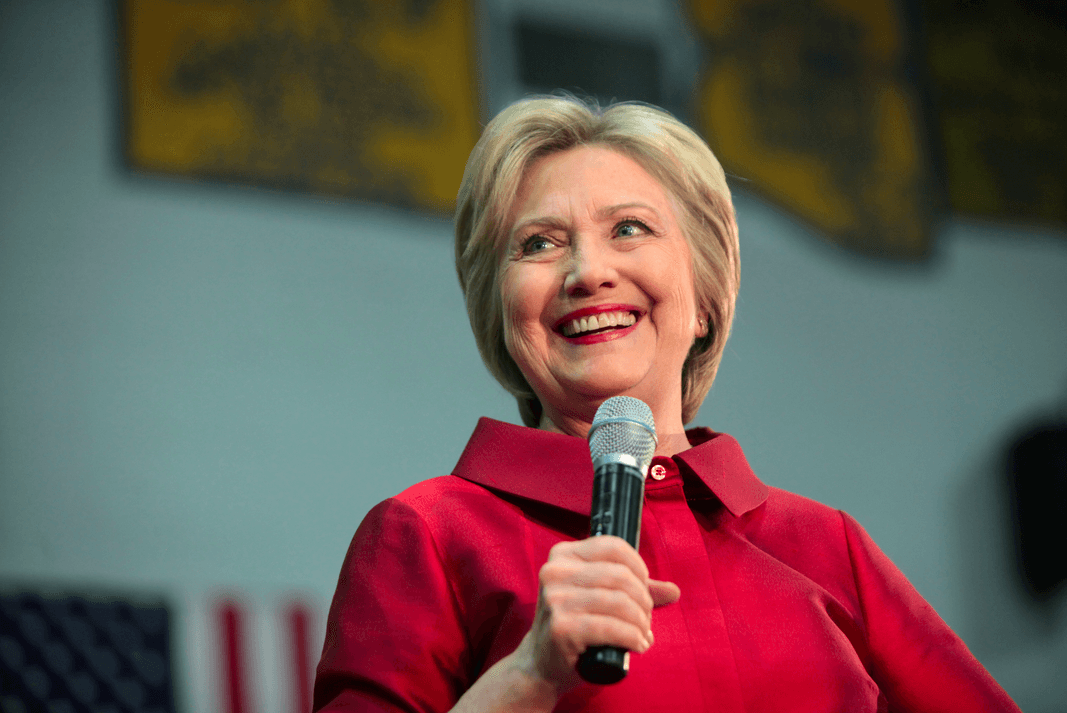

Hillary Clinton was evidently a centrist all along, prizing vague pragmatism, hawkish foreign policy and entrenched norms instead of a unique political vision.

Editor’s note: this essay is part of an ongoing series hosted by Quillette debating the merits and spirit of centrism. If you would like to contribute or respond to this essay or others in the series, please send a submission to [email protected].

The American political centre, which supported Hillary Clinton and rejected all arguments of her corruption, was hit last week hit with a political blow that, in ordinary times, would be a scandal capable of unwinding the entire Democratic Party. Donna Brazile, the former chairperson of the DNC, blew the whistle on the primary process a year and a half too late, telling many Sanders supporters exactly what they had suspected – that the Clinton campaign had been running the DNC since 2015. When Elizabeth Warren flatly stated on CNN that the primary was ‘rigged’, any notion of centrist unity around Hillary Clinton fell apart.

Absolute BOMBSHELL. Must read. Obama bankrupts the DNC and Hillary acts as loan shark. #berniewouldawon. https://t.co/bS3rN9Qlgu

— Josh Fox ✡️ 🤘 (@joshfoxfilm) November 2, 2017

Consider the two politicians who have arguably received the most disdain from Donald Trump: Hillary Clinton and John McCain. What do they have in common? Despite being supposed partisan rivals, they share nearly identical convictions when it comes to the influence of Wall Street in politics, foreign policy, the norms and decorum of Washington, as well as an air of elitism, a sense that they represent the “Old Guard” of their respective parties.

In the 2016 primary against Bernie Sanders, Hillary Clinton revealed that the central conviction of the Democrats is the same central conviction as the Republicans: the notion that money does not corrupt politicians. Clinton challenged Sanders directly when he implied that she was compelled to vote in certain ways due to donor money, boldly affirming that no vote of hers has ever changed due to the influence of a donor.

Of course, lifelong politicians find themselves in that position largely because their views already align with the expectations of the donor class. Clinton lied about her central political convictions from the start. Despite opposing Bernie Sanders, she moved perpetually toward the left throughout the primary campaign. She declared herself a progressive, and said that the only difference between herself and Sanders was that she had a steady hand on the revolving Washington wheel, as an expert handler of unwieldy leviathans. Fast-forward to her late 2017 book promotion cycle, and she proudly declares herself to be a centrist.

Hillary Clinton was evidently a centrist all along, prizing vague pragmatism, hawkish foreign policy and entrenched norms instead of a unique political vision. The 2016 election was not a contest between the left and the right, but rather a contest between the centre and Donald Trump’s new-right.

The simple truth is that there is no functioning left in the United States. The platform of Bernie Sanders, broadly summarised as a desire to reign in the power of banking institutions, provide a more robust social safety net akin to Canada, Australia and several countries in Europe, while disavowing the most toxic political actors such as Henry Kissinger, resembles the closest thing to a functioning left that the American system currently has. Social democracy is far from revolutionary socialism, and stands as a worthy consideration as an alternative to Trump.

Of course, Sanders lost the 2016 Democratic primary, and no excuses can be made for that. However, that still doesn’t mean that the primary process was just. The Democratic National Committee as an organisation is self-evidently corrupt, as Brazile has now documented. In a long-running lawsuit against the DNC that was settled in August, Bruce Silva, a DNC lawyer, argued that the DNC was a private organisation possessing the right to favour a specific candidate. Silva said:

The party has the freedom of association to decide how it’s gonna select its representatives to the convention and to the state party… Even to define what constitutes evenhandedness and impartiality really would already drag the court well into a political question and a question of how the party runs its own affairs. The party could have favored a candidate. I’ll put it that way.

According to Dave Weigel’s reporting at The Washington Post: “There was no evidence, the judge wrote, that anyone had donated to the DNC on the promise that the committee and its employees would be completely impartial.”

The precedent set here is so blatantly anti-democratic that it boggles the imagination. Despite the existence of only two functional political parties in the United States, the DNC, the single electoral bulwark against Donald Trump, is considered a private organisation that does not have to tether itself to the will of voters. If it chooses, it can prioritise a specific candidate, solidifying cronyism and financial influence as key elements of our electoral process, elements that selected Hillary Clinton and her centrism against the threatening mini-revolution of social democracy in America.

The privatisation of politics, embodied by the DNC, is a clear-cut example of elitism against voters. The private dealings of technocrats and political hacks ultimately choose the candidate – not “we the people”. In that case, why would anyone vote at all? 2010’s Citizen’s United, in ruling that money is the equivalent of speech, also set forth the troubling doctrine that democracy can (and should) be privatised.

The tension between democracy and unfettered markets is obvious: if money is speech, then the wealthiest of us get to jam our feet in the door and pass unpopular legislation. When Bernie Sanders criticises oligarchy, he is criticising precisely this corruption – the revolving door of lobbyists, the influence of corporate money in our politics, and the careerist bonds between the elite that form the networks running our civilisation at its highest levels. In fact, Sanders’ main problem with America could very well be described as Trump’s infamous “swamp”.

The phrase “Drain the Swamp” may as well have said, “Drain the Centrists”. The American political centre feigns neutrality, but the conformity of opinion found in our media, entertainment and political elites is enforced by money, not just good ideas. The political centre is not the centre because it is neutral, but because that is where the mass of power settles.

Take, for example, the recent panic over Russian Facebook ads swinging the election. For decades, virtually no American centrists have raised sustained concerns about the influence of money in politics, certainly not the legacy media. Even so, $100,000 in Russian Facebook ads has now supposedly undermined our democracy and made Donald Trump president, causing countless media outlets to breathlessly cover this never-ending scandal. Are we supposed to believe that an advertising budget lower than Jeb Bush’s New Hampshire radio campaign stopped Hillary Clinton? Furthermore, why does the Russian origin of the ads utterly discredit them, but propaganda bought by private Americans, likely the same Americans who fund newspapers like The Washington Post, is not considered problematic? Surely the fact that Jeff Bezos, the richest man on Earth, also owns The Washington Post presents no shortage of conflicts of interest. Yet, like with Hillary’s donor record, we are supposed to believe out of faith in our elites that there is no foul play.

The entire ‘Russian election meddling’ narrative is among the most elitist concerns in America. It reflects a tacit acceptance of financial disturbance in our democracy that is only upsetting when other nations do what we allow our own professional class to achieve each and every day. In the ultimate contradiction, centrist media have evoked nationalism to make us care about this issue, the same nationalism they decry in Trump as racist and exclusive. The Russia narrative is nothing but an attempt to shift blame away from the failures of centrism to stop Donald Trump and onto an amorphous foreign enemy.

The Democratic Party may have moved left on identity politics, but it has only moved farther right on economic policy. Nancy Pelosi, despised by conservative America as the epitome of a West Coast leftist, supported Clinton, not Sanders. Virtually the entire Democratic Party supported Clinton, because most Democrats are party loyalists, and prefer centrism to social democracy. Pelosi voted for the Iraq War, the Bush tax cuts and the Patriot Act. She, like Hillary Clinton, is opposed to universal healthcare and free college tuition. Where exactly is the rampant socialism here?

In America, the centre only survives based on deception. Cultural wedge issues create two polarised sides, but these sides converge in ways that escape mainstream political discourse. Democrats and Republicans are united not only in their almost uniform rejection of Sanders-style social democracy, but also on the role of the military.

George W. Bush, in the wake of 9/11, had a 90% approval rating for a brief moment in time. What did this approval lead to? A completely bipartisan passage of legislation designed to restrict civil liberties in the name of ‘security’, and a completely bipartisan Middle East war campaign that indisputably wrought horror on the region. Obama’s bombing of Libya, with Hillary Clinton as his Secretary of State, has now led to a failed state with open-air slave markets. Hundreds of thousands of Iraqis died on bipartisan consensus, and international law was violated as Democrats and Republicans turned a blind eye to torture and mass surveillance, contraventions of the spirit of both international and domestic law.

When a US drone strike killed Abdulrahman al-Awlaki, a 16 year old US citizen and innocent son of a dead terrorist, the US media and political centre hardly batted an eye. The clear overturning of Magna Carta principles – the right of the sovereign to kill his own citizens anywhere in the world without due process – was not seen as a threat to our values. There was no major scandal, no David Frum to emerge and defend the constitution. If a US citizen can be killed abroad by the President without controversy, then it is chilling to think of the potential consequences for non-citizens.

There is certainly room for a legitimate debate on the role of surveillance and war in the 21st century, but as it stands, only fringe figures like Dennis Kucinich and Rand Paul have ever represented a dissenting position in office. When Donald Trump railed against Jeb Bush over the Iraq War in the Republican Primary debates, he was placing himself in unique political territory, and new political territory is clearly what is needed.

A return to the centrism of figures like Hillary Clinton and John McCain will never inspire Americans. Especially now that we have seen that the absurd is possible, that Donald Trump can become President, and that Washington’s veneer of polish and condescension has thinned to the point of evaporation.

Alexander Blum is a science fiction novelist with an interest in Jung, Christianity, and accelerationism, looking to face total digital consumption while preserving the essential characteristics of the human spirit. Follow him on Twitter @AlexanderBlum0