Art and Culture

On Truth and Beauty

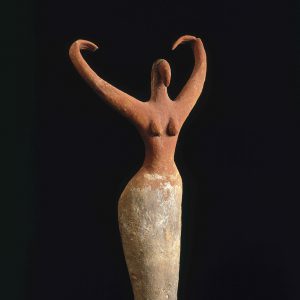

The model was indeed full-figured, and her presence will come as a kind of reassurance to anyone who today considers themselves overweight.

To my great surprise I found myself reading a Buzzfeed listicle the other day. The piece: “Women’s ideal body types through history.” The contents: various images of a diverse cast of models showing how beauty standards have changed over time.

One of the first things that struck me as I skimmed the article was that while female beauty standards do seem to have changed over time (though not too much — almost all the models were slim) it’s curious that the ideal male form hasn’t changed at all; Michelangelo’s David is as beautiful in 2017 as he was in 1517 and can expect to be in 2517.

I learned that the Ancient Egyptians believed long braided hair was an important aspect of female beauty. Braids “framed a symmetrical face”, and the most desired women were slender, with high waists and slim shoulders. (The “Ancient Egyptian” model was African-American, although Ancient Egyptians are more likely to have resembled other Mediterranean peoples.)

Chinese women of the Han Dynasty (c.206BC – 220AD) were expected to have long black hair, red lips and white teeth, among other things. But also on the list was pale skin, and unless you’ve been living under a rock since the 1960s you’ll know that no shortage of intellectuals have blamed the desire for pale skin on the nefarious effects of colonialism. That its presence was a beauty criterion as long ago (and as far away from Europe) as Han China is telling, to say the least.

Next was the beauty of Renaissance Italy, exemplified by a “rounded body, including full hips and large breasts”. The model was indeed full-figured, and her presence will come as a kind of reassurance to anyone who today considers themselves overweight.

The Renaissance prototype was the only model like this; the rest were comparatively slim, suggesting frontiers to human subjectivity when it comes to body mass. I don’t want to belabour this idea that beauty standards change over time, but I’ll give a brief rundown of the others. In Victorian England, the smaller the waist the better. Androgynous women were popular in the 1920s. Beauties back in the 1950s had “curvy” figures. Athletic, buxom supermodels defined the 1980s, heroin chic waifs the 1990s. Finally we arrive at today, where we are told women should “be skinny, but healthy, and have large breasts and a large butt, but a flat stomach.”

There are a number of telling insights into the article’s postmodern thinking. Consider the following phrase: “Women in the 2000s have been bombarded with so many different requirements of attractiveness.” No relativism here: modern women are being assaulted with an unprecedented, uniquely bewildering and unattainable array of demands. But are the standards women aspire to today any less obtainable than those women faced in the past? Women in Han China were expected to have white skin in an age of ubiquitous, rice-paddy agriculture, and perfect teeth in an age before dentistry in any recognisable form. To have good teeth in the Iron Age you needed to hit a genetic lottery in teeth. You had to be exceedingly lucky.

The demands supposedly placed on modern women, as claimed in the article, are highly suspect. The desire for a “large butt” is hardly universal today, though most would agree that slimness is a trait considered positive by a majority of men and women. By informing us of the diverse beauty standards throughout history I imagine it is the author’s intention to inform us of beauty’s subjectivity; that it is relative to time and space. But that is not the impression we get reading the article. Prior societies’ ideals are elucidated, and they are not vague and inchoate but authoritative and fully formed. The Egyptians, Greeks, and Victorians knew what they liked. For our distant ancestors, beauty was not subjective.

The top rated comment under the article makes the point that “we’re all beautiful” and notes the fickleness of humanity’s beauty standards. But this claim is only true if we live in a chaotic civilisation with a crippled sense of aesthetics — something that may well be the case at this point. Our present perception of the world — our own, modern truth — is being dismissed by people for whom reality is merely an opinion. Little wonder the average person in the street is confused by modern art. For if everything is beautiful then nothing is.

There exists the culturally destructive assumption that today’s standards are immutable, but they are not. They too will fall victim to humanity’s aesthetic caprice.

The modern Westerner (other civilisations’ aesthetics are not under attack) is expected to look at an assortment of body shapes and sizes, admire them all and view every one as equally attractive. But science has profoundly impacted our understanding of beauty in the sense that modern medicine informs us of obesity’s devastating effects on human health.

People of every age have had standards of beauty unique to them. Tiny waists were beautiful for the Victorians, female obesity is beautiful for contemporary Mauritanians, white skin was (and still is) beautiful to the Chinese. Those were their truths. It is only modern Westerners who are told that they cannot embrace their own truth, that their aesthetics are wrong, that literally every woman in the world is beautiful.

Sir Roger Scruton once said — and I’m paraphrasing here — that anyone who says there are no truths or that all truth is “merely relative” is asking not to be believed.

So don’t believe them.