Science / Tech

America’s Public Health Is Under Attack

The hepatitis B vaccine episode is a preview of what happens when scientific institutions are corrupted by people who reject the scientific method itself.

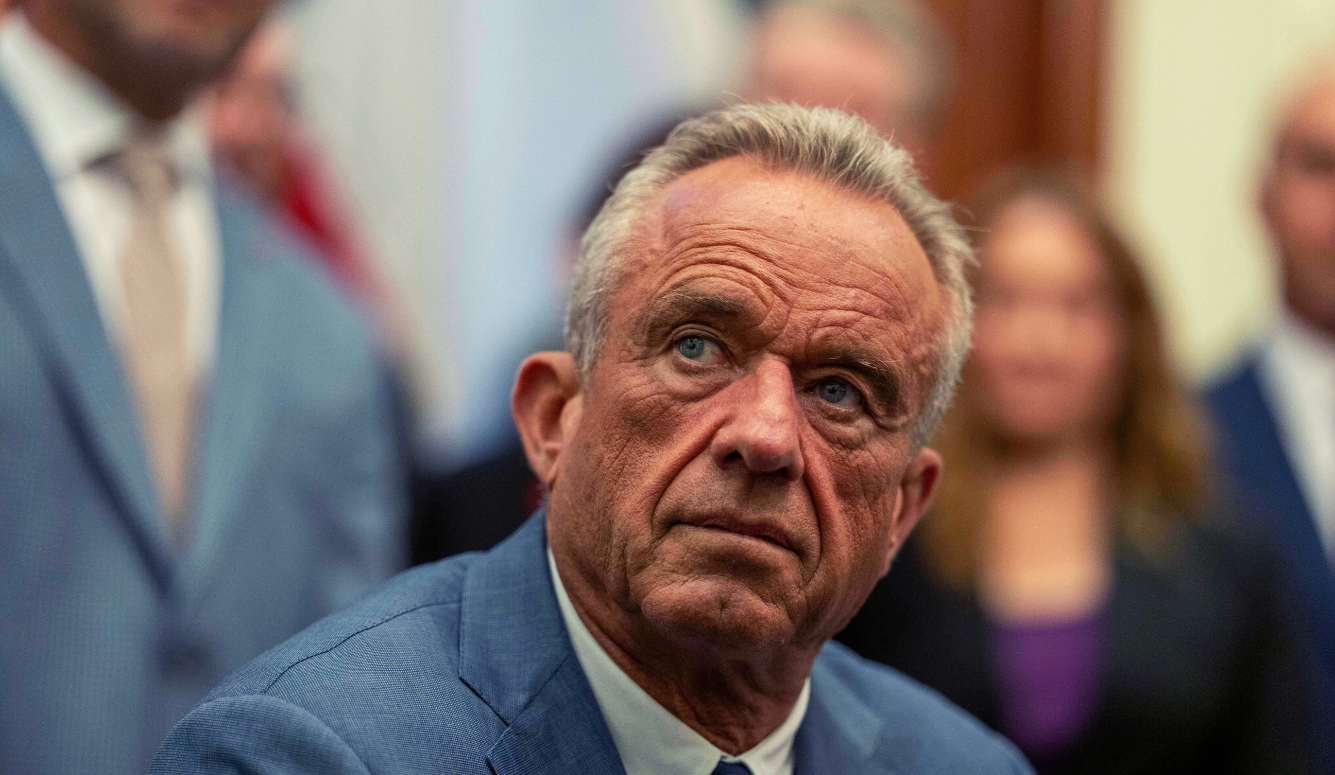

With the federal government now back open after the recent shutdown, one critical vehicle for formulating public health policy is immediately plunging back into chaos. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP)—the expert body at the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) that for decades has, inter alia, guided the nation’s vaccination schedule—has been radically remade by Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. And now, Kennedy’s ACIP, repopulated with cranks and misfits, is racing ahead with dismantling the nation’s hugely successful childhood vaccine schedule.

A meeting originally planned for October but then paused has been abruptly rescheduled for December 4–5, according to a terse notice in the Federal Register. The agenda is somewhat vague, but it is clear that a vote on hepatitis B vaccine recommendations is expected. Given this committee’s recent pronouncements, many paediatricians and public-health officials expect another attempt to weaken or delay standard childhood immunisations.

Pre-Kennedy, the ACIP was one of the federal government’s most respected scientific advisory bodies. Its members included infectious-disease specialists, epidemiologists, paediatricians, virologists, and public-health researchers who spent years accumulating expertise, then underwent extensive vetting before being appointed. For decades, the committee earned bipartisan trust by grounding its vaccine recommendations on meticulous, transparent deliberations. But this is no ordinary moment. And this is no ordinary ACIP.

In June, Kennedy abruptly fired all seventeen existing ACIP members and replaced them with twelve new appointees, almost all of whom lack relevant expertise and are on record expressing anti-vaccine views. One member is a naturopathic doctor known for opposing infant vaccination. Another is a psychiatrist whose public work involves fringe nutritional theories rather than immunisation science. Another has repeatedly promoted scientifically debunked claims about childhood vaccines on social media.