John Lennon

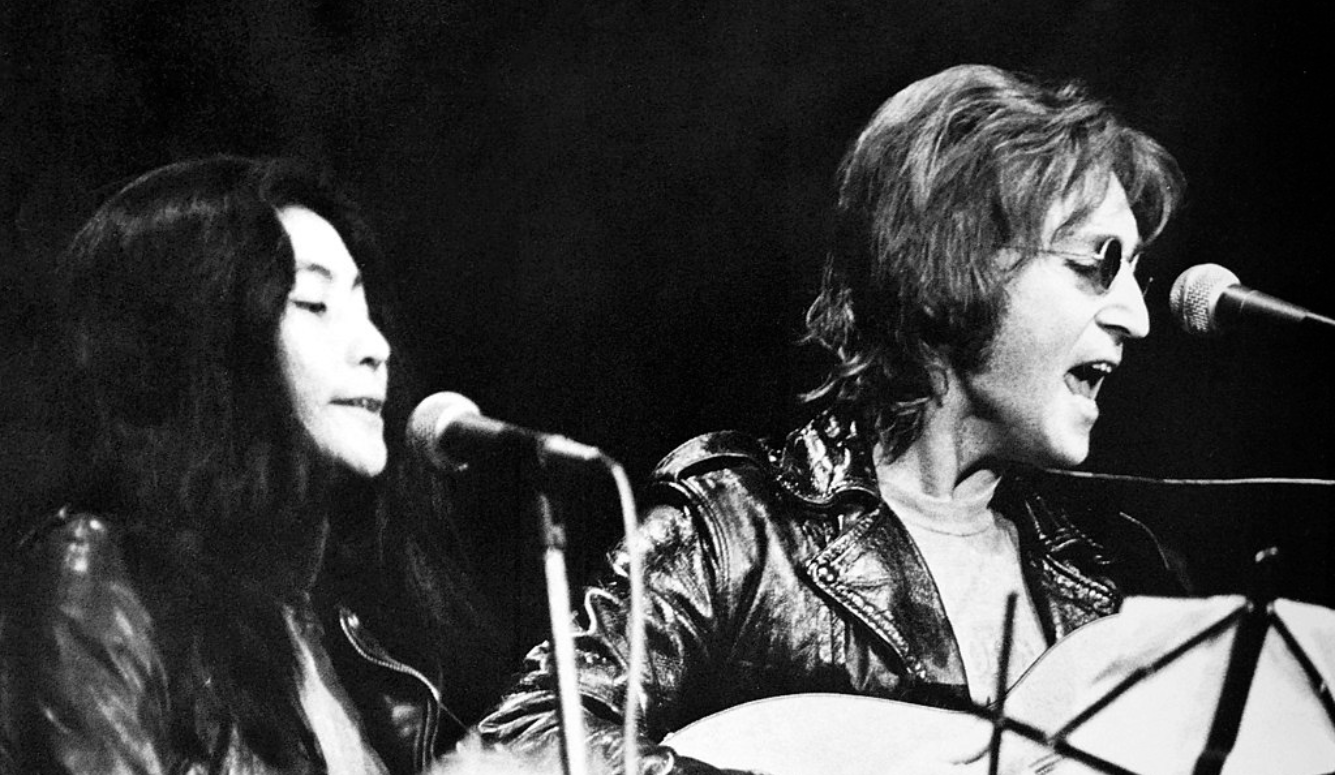

Censoring John and Yoko

Power To The People sparks a debate over art, censorship, and John Lennon’s legacy.

Curating a Legacy

John Lennon was always the most controversial Beatle. In 1966, he infamously declared, “We’re more popular than Jesus,” sparking a backlash that led to public bonfires of Beatles records. In 1968, he appeared nude on an album cover with Yoko Ono, leading retailers to be jailed on obscenity charges. And, in 1969, he starred in a short film focused on a single part of his body in varying states of tumescence—the less said about that, the better.

Even today, 45 years after his death, Lennon continues to ignite controversy. The latest surrounds a recently announced twelve-disc boxset, focused on Lennon and Ono’s recordings of 1971–72. These were their most politically direct songs, tackling specific issues of the time—from the Attica State Prison riots to the trial of Angela Davis. The songs came together on the double album Some Time in New York City. They also formed the backbone of the One to One concerts at Madison Square Garden, which were the subject of a recent documentary.

The new controversy stems from the boxset’s omission of a key Lennon-Ono song from the period: “Woman Is the Nigger of the World.” On the original release of Some Time in New York City, this provocatively titled track opened the album. It was also the centrepiece of the album artwork. Designed to look like a newspaper (with each song name as a headline), the cover featured that arresting title in the most eye-catching position possible. It was also the only single issued from the album.

Despite being the central Lennon-Ono song of that period, it does not appear a single time across the boxset’s exhaustive 123 tracks. The album it originally appeared on is now presented in a “reimagined” version, with the offending song removed and another track reordered into the opening slot. Likewise, three discs dedicated to the One to One concerts omit the song, despite it having been performed at the shows.