Art and Culture

Disco Inferno

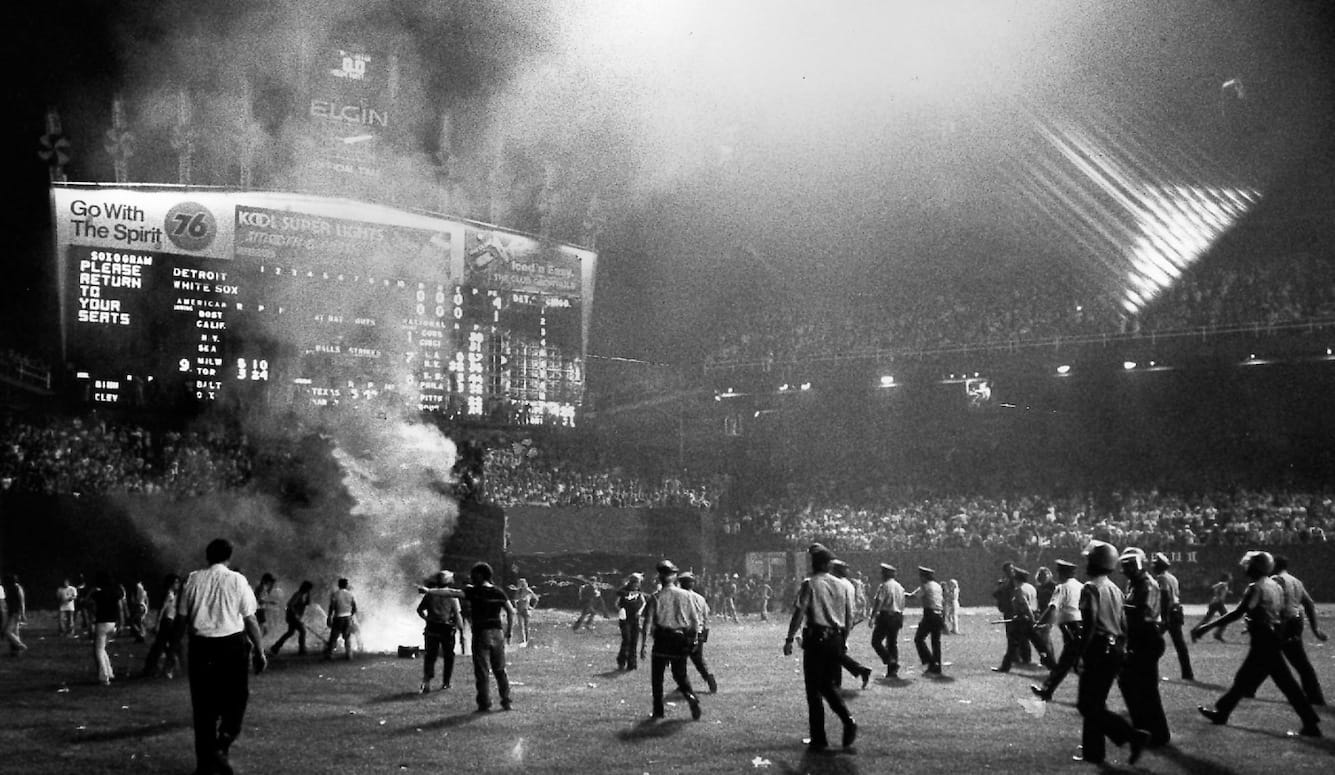

Disco Demolition Night was an early episode of culture and counterculture being saddled with far greater political significance than they deserved.

These days, it’s not unusual for entertainment news to become fodder for solemn think-pieces about current affairs and the state of society. But five decades ago, there was a clearer division between the editorial pages and the arts and sports sections. So, when a promotional stunt during a baseball doubleheader in Chicago turned into a small riot in July 1979, the incident was not expected to make national headlines. But the initially fringe and unclassifiable story of Disco Demolition Night would come to exemplify how politics is downstream from culture: an early episode of pop styles, and reactions to them, being saddled with far greater significance than they deserved.

By 1979, the disco phenomenon had just about peaked. The genre had evolved out of its earlier soul and funk forms to become the aural environment of dedicated dance clubs, where the gritty grooves of James Brown or Motown had been polished into a silky metronomic sound gleaming off a mirror ball. Discotheques were not made for watching live performances by musicians, but for attendees to lose themselves in uninterrupted flows of recorded songs. Disco broke big with the 1977 release of Saturday Night Fever, a hit movie that showcased the smooth footwork of young John Travolta in the starring role. The film’s success was augmented by the synergistic tie-in of its soundtrack album, featuring the Bee Gees’ “Stayin’ Alive,” and “Jive Talkin’,” the Trammps’ “Disco Inferno,” and other numbers, which eventually sold forty million copies internationally.

On screen and on record, Saturday Night Fever propelled a wave of subsequent disco product, including the movies Thank God It’s Friday (1978), Roller Boogie (1979), and Xanadu (1980), hit singles such as Donna Summer’s “Hot Stuff” and “Bad Girls,” Alicia Bridges’s “I Love the Nightlife (Disco ’Round),” Gloria Gaynor’s “I Will Survive,” Earth, Wind and Fire’s “Boogie Wonderland,” the Village People’s “YMCA” and “Macho Man,” and a stack of compilation albums like Disco Nights, Disco Super Hits, and Disco Fever 1979. Even hard-rock acts hustled aboard the disco bandwagon with records like the Rolling Stones’ “Miss You,” Kiss’s “I Was Made For Loving You,” and Rod Stewart’s “Do Ya Think I’m Sexy,” which pulsed out everywhere from the dance floor of Studio 54 in New York to small-town roller-skating rinks across the heartland. For a few months, in the hothouse of consumerism and youth taste, the disco sound, look, and sensibility was everywhere.

But in the last year of the decade, a backlash against disco got underway. Suddenly “Disco Sucks” and “Death Before Disco” T-shirts and posters were flying off the shelves, while the novelty tunes “Disco Sucks” and “Disco’s in the Garbage” were heavily rotated on rock radio stations. Disco became an insult directed at instances of vanity and preening (as in “That guy’s so disco”). This wasn’t just a matter of disco album sales falling off or disco bars emptying out as listeners moved on to the Next Big Thing, it was an aggressively anti-disco movement attacking the songs, the performers, and the fans. And the campaign didn’t originate with concerned parents or prudish squares, but with a rival sector of the entertainment market: young rock ‘n’ rollers, media programmers, and others with a stake in the same popular art form from which disco itself had emerged.