Art and Culture

Religious Reasoning

The first and largest mistake Douthat makes in his new book is to argue that faith and rationality are mutually supportive.

A review of Believe: Why Everyone Should Be Religious by Ross Douthat, 288 pages, Zondervan Books (March 2025)

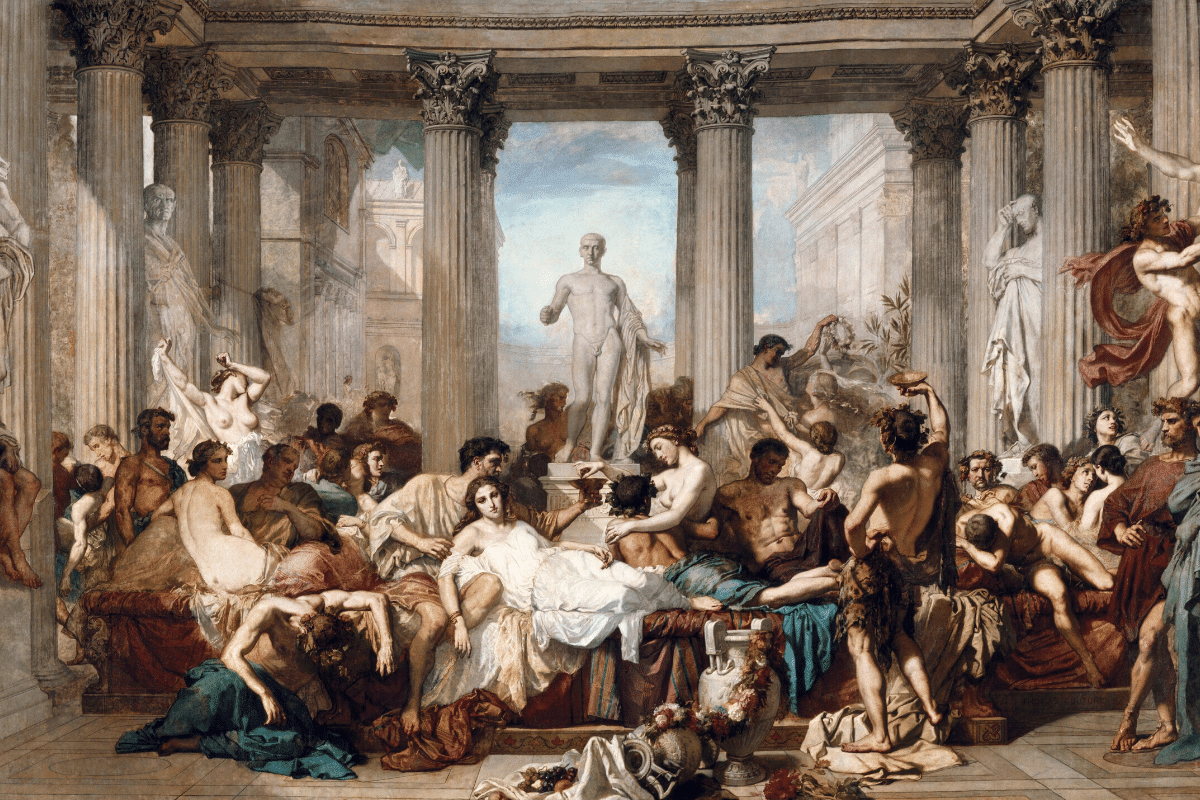

The past few centuries haven’t been especially kind to God or his followers. There was Galileo, then Hume, then Laplace, then Darwin, then Nietzsche, then the Scopes Monkey Trial. (The religious side technically won that last encounter, but it was a pyrrhic victory). Churchgoing steadily waned. Philip Larkin wondered what we’d do with houses of worship once they fell out of use. The early 2000s were especially rough. The Catholic Church was buffeted by a massive sex-abuse scandal. Sam Harris, Christopher Hitchens, and Richard Dawkins became intellectual rockstars by mercilessly attacking religion. Thousands of people flocked to hear them speak, and thousands more flocked to buy their books. If God was not quite dead yet, He seemed to be nearing retirement.

But religion has been making something of a comeback lately. According to a recent Pew survey, the number of people who identify as Christians—a figure that had been declining for decades—appears to have levelled off, at least for the moment. It hovered around 63 percent in 2019, and that’s approximately where it stands now. In England, church attendance has actually increased among Generation Z. Rather than turning to the Church of England, younger congregants have been joining showier denominations like Catholicism and Pentecostalism. The rise of wokeness and the cult of personality that sprang up around Donald Trump have led some people to speculate that there’s a “God-shaped hole” in contemporary culture. “As religion has receded from people’s lives,” sociologist Jonathan Haidt has explained, “they’re hungrier. As I see it, politics has really taken the place [of religion].”

Some once-stout atheists and agnostics have begun to reconsider their antipathy to organised religion. “Maybe religion, for all of its faults, works a bit like a retaining wall,” the agnostic Derek Thompson recently wrote in the Atlantic, “to hold back the destabilizing pressure of American hyper-individualism.” Another Atlantic writer (and nonbeliever), Jonathan Rauch, has argued that America needs to return to its Christian roots. In 2023, Ayaan Hirsi Ali, the famed Islamic apostate and New Atheist fellow-traveller, announced that she, of all people, had found Jesus. “I ultimately found life without any spiritual solace unendurable,” she explained. “Atheism failed to answer a simple question: What is the meaning and purpose of life?”

One of the loudest cheerleaders for the current religious revival is opinion columnist Ross Douthat, a conservative and a Catholic, who for years has used his perch at the New York Times to sing the praises of faith. Douthat has a new bestseller out titled Believe: Why Everyone Should Be Religious, in which he argues that belief in God is not only socially beneficial and emotionally fulfilling—as Thompson, Rauch, and Ali contend—but also scientifically sound. “It is the religious perspective that grounds both intellectual rigor and moral idealism,” he writes. “And more important, it is the religious perspective that has the better case by far for being true.”

Douthat is an intelligent man, and he’s written several well-reasoned books—on the Republican Party, on the decadence of modern society, and on his own harrowing battle with Lyme disease. This is not one of them. He blows past entire branches of science and philosophy in just a few paragraphs, behaving as if he’s solved puzzles that, in fact, he’s barely touched. For instance, the question of why a benevolent personal God would allow good people to suffer has been perplexing thinkers since the Book of Job. But Douthat believes he has that problem licked:

The moral case against Almighty God assumes a version of the very premise it ostensibly denies—that human beings are so distinctly fashioned among all the creatures of the world that we are equipped to stand outside material creation and comprehend it so completely as to make a certain moral assessment of how good and evil are balanced in the cosmos.

In other words, God works in mysterious ways; don’t try to figure it out. Douthat has simply redefined goodness so that anything God deems to be good must be good. Plato pointed out the illogic of this position more than 2,000 years ago. “The point,” he wrote, “which I should first wish to understand is whether the pious or holy is beloved by the gods because it is holy, or holy because it is beloved by the gods.” The 20th-century philosopher Bertrand Russell summed up the same thought in his 1927 essay “Why I Am Not a Christian”:

If you are going to say, as theologians do, that God is good, you must then say that right and wrong have some meaning which is independent of God’s fiat, because God’s fiats are good and not bad independently of the mere fact that he made them. If you are going to say that, you will then have to say that it is not only through God that right and wrong came into being, but that they are in their essence logically anterior to God.

Not all Douthat’s assertions are this fatuous. He begins the book with his strongest points, starting with the fine-tuning argument—the idea that the universe was designed with life in mind. He cites the religious physicist Stephen M. Barr, who noted just how exquisitely balanced our cosmos is in his book Modern Physics and Ancient Faith. Change the cosmological constant a fraction and the entire universe would come apart. Adjust the gravitational force a bit and stars would never form. Alter the nuclear force a tad and hydrogen atoms would vanish. As Douthat writes, “No hydrogen, no water; no water, no us.” Even Christopher Hitchens, one of the most pugnacious New Atheists, acknowledged that this was one of the better arguments marshalled by believers.

Still, it isn’t especially persuasive. It is essentially an updated version of William Paley’s watchmaker analogy, coined more than 200 years ago, which likened the natural world to a pocket watch. If someone who had never seen a watch before found such a device lying in a field, he would immediately know that it had been designed for a particular purpose by an intelligent mind. And just as a watch must have a watchmaker, the complexity of the natural world demands an intelligent designer. But this reasoning was made obsolete by Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection, which elegantly explained how complex life forms could emerge and develop without the assistance of a deity. The fine-tuning argument simply broadens the same analogy so that it explains the universe rather than life on Earth.

The problem is that, for a place that’s supposedly fine-tuned to produce life, the universe is conspicuously short of the stuff. Even if another “Goldilocks planet” exists somewhere in the vastness of space (as some scientists suppose), replete with air and water and conscious creatures like ourselves, the majority of the cosmos is cold and empty—not just devoid of life but positively inimical to it. The nearest planet to our own that might sustain life is Proxima Centauri b., more than twenty trillion miles away. As social psychologist Bo Winegard pointed out in his own review of Douthat’s book, “Asserting that the universe was fine-tuned for life simply because life exists on one tiny planet in our immense cosmos is like claiming that a spot of mold in a Gothic mansion proves the house was built for the mold.”

Douthat also wonders about consciousness. Scientists have learned an enormous amount about the workings of the brain, he writes, but they are no closer to explaining how consciousness emerges: “Redescribe as you will, reduce as you may, nobody has any idea how or why the physical inputs that go into conscious experience, the stimuli from particular chemicals or light waves or exchanges between neurons, yield the actual experiences themselves.” On top of this mystery, Douthat layers others: “How,” he asks, “can light be both a wave and a particle? How can particles remain somehow ‘entangled’ even when separated by a great distance? And above all—how can human observation be the only thing that transforms quantum contingency into definite reality, wave into particle, probability into certainty?” Douthat’s answer to these rhetorical questions is that mind and matter are entwined because mind precedes matter.

It doesn’t take a degree in either neuroscience or quantum physics to see that Douthat is simply swapping one mystery for another. The hard problem of consciousness has stumped scientists for years, but invoking a divine creator does not provide a satisfactory answer. Douthat could just as well use the word magic to explain the emergence of consciousness. That, at least, would provide a more parsimonious explanation of cause and effect. After all, if conscious minds need a conscious creator, the next obvious question is who created the creator? The same goes for wave-particle duality. Saying the existence of God explains how light can be either a particle or a wave, depending on how it’s observed, is simply a way of dumping the conundrum on the Almighty. Douthat, in short, is postulating a “God of the gaps,” squeezing Him into the crevices that scientific knowledge has yet to fill. In the past, religious apologists have generally been wary of resorting to such arguments because they recognise that the gaps have been shrinking over time as we learn more about material reality. A God of the gaps is, by definition, a God of diminishing importance.

These problems notwithstanding, the first two chapters of Douthat’s book are an enjoyable read. If he’d put his pen down once he’d completed them, he’d have produced an interesting (albeit very short) book. Unfortunately, he tries to expand his deistic claims into an evidentialist case for a personal God with a Christian complexion.

The difficulty for anyone making such a case is that all religions look parochial when traced to their roots. To be a believing Christian or Jew, for instance, one must accept that the creator of the universe gave the bulk of his wisdom to a single desert tribe in Iron-Age Palestine—a time and place rife with ignorance and superstition. Why didn’t He decide to deliver this important message in a more cosmopolitan city like Alexandria or Rome, where his pronouncements could more easily be recorded and circulated?

And why didn’t He reveal it in multiple locations across the globe to ensure the widest possible dissemination as well as uniformity of belief? Instead, people in far-flung corners of the Earth who had never heard of Jesus of Nazareth were left to come up with their own supernatural and mythological explanations for phenomena they didn’t understand. H.L. Mencken illustrated the absurdity of choosing any one god by producing a list of the many deities that are now defunct. His list—which includes Jupiter, Baal, Huitzilopochtli, Rigantona, and Ma-banba-anna—runs to more than 140 names.

Douthat has a fondness for cartographic metaphors, and he tries to bypass this obstacle by arguing that all religions lead you to “the same destination in the end”:

Suppose you were in Bangor in 1887 and you wanted to reach Topeka and you were told that there were five excellent maps, from very different mapmakers, offering very different itineraries, that would all eventually lead you from Maine west to Kansas. Would it make sense to say, Well, since they all get you there eventually, I’m sure I can just draw my own map and get the same result? Would it make sense to stitch pieces of them together, rejecting the boring or grinding parts of each route, on the theory that this way your journey would be nothing but fun visits to neat roadside attractions? Of course not. If you want to reach Topeka, the fact that you respect all the different mapmakers equally doesn’t absolve you of the requirement to choose one, to follow, to submit.

There’s a lot to dislike in this analogy. For a start, it assumes something it hasn’t established. Topeka was a verifiable place in 1887; a better analogue would therefore be Shangri-La, the magical Himalayan valley in James Hilton’s 1933 novel Lost Horizon, from which no visitor has ever returned. And you’ll notice that the word “itineraries” is doing a lot of work in that passage. The itinerary for the Heaven’s Gate sect involved mass suicide. The itinerary for Christian Scientists involves denying medical care to their children. The itinerary for many Muslims involves imprisoning women in black shrouds and putting apostates to death.

Douthat takes an ecumenical approach to such matters, allowing that all religions have some good and bad in them, and some truth and falsity. The trick is picking an itinerary that suits you:

Do you wish that Christian churches only emphasized Christ’s teachings about helping the poor, or that synagogues only preached tikkun olam, the repair of the world, instead of fussing over people’s gender roles and sex lives? If you inhabit any major US city you can find a church or synagogue that tries to do exactly that.

But there’s an obvious difference between choosing a religion because it matches your priors and choosing one because you believe it is true. Indeed, if a religion matches your priors too closely, it probably isn’t true. As he does with so many other epistemic quandaries, Douthat shrugs this one off. Better to believe in something than nothing. At least then your soul will have a chance. “Better to face the consequences of even a mistaken commitment or decision than to hear, at the last, the fateful judgement, ‘because you are lukewarm, and neither hot nor cold, I will spit you out of my mouth,’” he writes, quoting the Book of Revelation.

This is a version of the wager devised by the 17th-century mathematician Blaise Pascal. If God exists, Pascal reasoned, piety will be rewarded in the afterlife; if God does not exist, you won’t even be in a position to regret the time you wasted on Sundays. There are several questionable things about this rationale. First, it assumes there’s only one god on offer, or there will be no price to pay for selecting the wrong one. Second, it provides bad reasons for doing a supposedly good thing, as even many theologians have acknowledged. “If I adore You out of fear of Hell, burn me in Hell!” the Muslim mystic Rabia al Basri wrote more than a thousand years ago. “If I adore You out of desire for Paradise, Lock me out of Paradise.” And third, this ruse doesn’t convey a very high opinion of the Almighty. Pascal and Douthat assume that God can either be fooled by self-serving encomiums or that He prefers insincere worship to intellectual honesty.

So how should a person choose their religion from the many available options? According to Douthat, it’s best to follow the crowd:

Start the way you would in any other area—by looking for wisdom in crowded places, in collective insights rather than just individual ones, in traditions that have inspired entire civilizations, not temporary communities. Even if you can’t know for certain which road leads closest to the truth, you can still assume that the better trodden a religious pathway, the more wisdom there is in following after the generations that have trodden them before.

Douthat acknowledges that this rule of thumb isn’t perfect. All big religions were small at one time. And a belief isn’t necessarily true just because a large number of people subscribe to it. Still, he writes, “the big and important religions are big and important for a reason.” This leads him into a justification of his own religion, one of the biggest and most important of them all:

I am open to hidden complexities and unexpected syntheses, but in the end I think that God has acted in history through Jesus of Nazareth in a way that differs from every other tradition and experience and revelation, and the Gospels should therefore exert a kind of general interpretative control over how we read all the other religious data.

This is where Douthat discards all common sense. The gospels, most Biblical historians agree, were written decades after the crucifixion by people who’d never met Jesus or, in all likelihood, any of his apostles. Nor do they make all the claims now central to most iterations of Christian doctrine. As the religious scholar Elaine Pagels has pointed out, “These early gospels [Matthew, Mark, and Luke], read in their first-century context, do not support the theological assumptions enshrined, for example, in the Nicene Creed, which declares, in effect, that Jesus is God incarnate—creeds that Christians wrote centuries after Jesus lived.”

Douthat has no time for experts like Pagels. He prefers to rely on sources like the Christian historian Peter J. Williams, who regards the Bible as the inerrant word of God. Douthat writes:

The four gospels all date plausibly to the earliest generations of the church. The Gospels display a deep familiarity with the landscape and culture of their setting: the local geography and topography, the names of minor towns as well as cities, the descriptions of certain features that archaeology has only recently discovered, the names that would have been popular at that time and place, and more.

Sure, they contain discrepancies, he admits, but these can be chalked up to normal human error:

The variations in which day a particular event took place, who was present for a given miracle, which exact words someone used, are precisely what you’d expect from a collection of authentic testimonies that weren’t smoothed out into propaganda.

These passages lean heavily on Williams’s 2018 book Can We Trust the Gospels?, which Douthat describes as “pellucid.” Superficial would have been a better term. Though Williams claims to address historical criticisms of the gospels, he ignores many of the biggest anachronisms and inconsistencies in the texts, including the contradictory accounts of Jesus’s birth and his resurrection, the ahistorical descriptions of Pontius Pilate and the Jewish Sanhedrin, and the story of a massive census, for which there is no historical evidence.

Williams acknowledges that he is not an historian in the usual sense, since he works backwards from his preferred conclusion rather than forwards from the available evidence. When his unusually early dating of the gospels was challenged by historian Bart Ehrman, his confidence crumbled. The fact that Douthat puts so much stock in such an obviously unreliable and biased source only underlines how dependent his conclusions are on motivated reasoning. When the gospel authors get something right, he cries, “See how factual they are!” When they get something wrong, he says, “Well, that’s just the kind of mistake an honest person would make.”

This desire to have things both ways plagues Douthat’s thinking throughout the book. He wants to be an omnist who’s open to all varieties of religious experience and a good Catholic who thinks his own creed is more “God-touched” than the rest. He wants to say that belief really matters but it doesn’t really matter what you believe, just so long as you accept that there’s a deity (or deities) out there. As the contradictions accumulate, Douthat’s thesis—that a belief in God is entirely rational—begins to look increasingly dubious. How can he insist that faith is logical when the logic he uses to justify his own faith is so tortured?

Time will tell whether the current religious revival has legs. As an article in the New York Times recently pointed out, the trend lines still don’t look good for religion, despite the improvement registered by the Pew Research Center:

As the Silent Generation, Boomers and Gen X become a smaller and smaller share of the population, there will simply not be enough religious young Americans to replace them. “The reality is that 20 percent of boomers are nonreligious and it’s at least 42 percent of Gen Z,” about the same as millennials, said Ryan Burge, a political scientist and the author of The Nones: Where They Came From, Who They Are, and Where They Are Going. ... According to Pew, only 40 percent of American parents of minor children are giving their kids any kind of religious education. Only 26 percent go to religious services once a week. We will eventually become a country that is 40-to-45 percent “nones,” Burge said, though it will likely take a few more decades to get there.

If Burge and the Times are wrong—if, that is, religion really is on the verge of a comeback—it probably won’t be due to intellectual arguments like those advanced by Douthat in this book. You can reason yourself out of religion, as many people have done over the centuries, but reasoning yourself into it is a much more difficult task that requires a lot of mental gymnastics and double-entry accounting.

“Reason,” Martin Luther observed, “is the greatest enemy that faith has; it never comes to the aid of spiritual things, but more frequently than not struggles against the divine Word, treating with contempt all that emanates from God.” The first and largest mistake Douthat makes—his original sin, you might say—is trying to show that faith and reason are not enemies but friends, supporting one another in their conclusions. “Nonbelief,” he writes in the introduction, “requires ignoring what our reasoning faculties tell us, while the religious perspective grapples more fully with the evidence before us.” That word “evidence” crops up a further 33 times in the pages that follow, but when the evidence cuts against Douthat’s cherished beliefs, he ignores it.

Midway through the book, he states that the world’s religions are not incompatible with one another. Human history is filled with episodes of religious conflict and bloodshed precisely because they aren’t compatible. The New Testament, the Koran, and the Book of Mormon can’t all be the final revelation. If Brahma, Vishnu, and Shiva are real, Allah can’t be the one and only God. To pretend otherwise is not an empirical position, based on evidence. Nor is it a rational one, based on logic. It’s an act of faith.