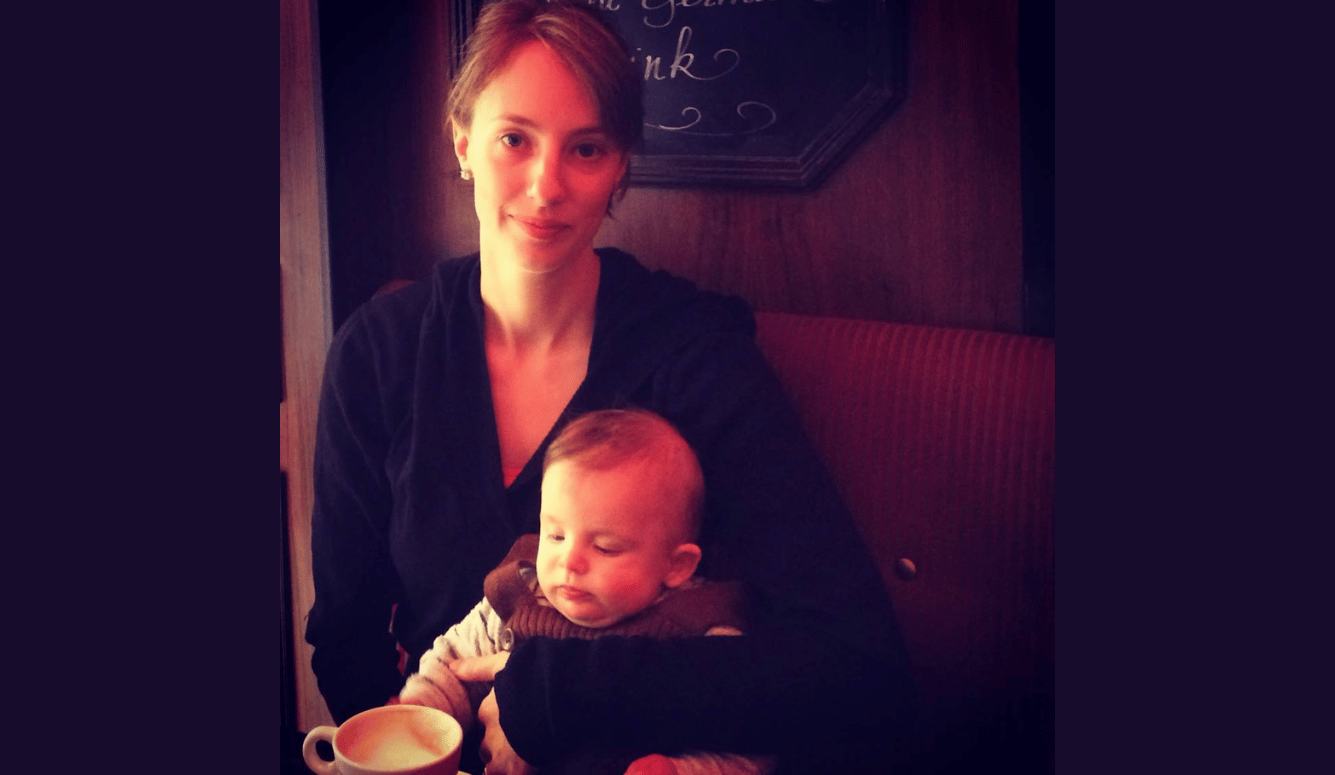

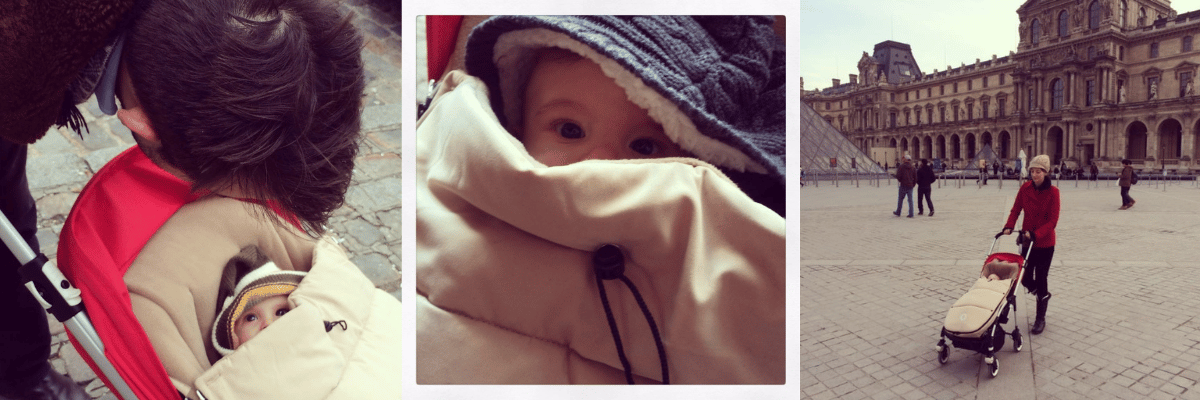

When my firstborn, Eric, was four months old, we found ourselves in France for Christmas. It was cold, of course, so we organised a tan-coloured woollen cocoon for his pram, and brown woollen dungarees to keep him warm. As we strolled through Notre Dame and the streets and parks of Paris—amazed by the city’s beauty—our new baby would peek up at us from inside his cocoon.

This was my first visit to Paris, so I naturally had to go to the Louvre. Not much in Paris is designed for new parents with babies, and the Louvre is no exception. We had to haul Eric and his pram up and down the stairs all day. When we were not hauling, Chinese tourists in the ladies’ bathroom would coo at him and take photos while I changed his dirty nappy.

Yet walking those palace halls as a new mother, I came to feel that I was witness to something remarkable. In room after room I was met by paintings of baby Jesus with his mother Mary—a mother-child dyad in which two figures exist in perfect harmony. The Louvre houses over a hundred paintings titled “Virgin and Child,” yet even this impressive number doesn’t capture the full scope of these maternal scenes. They appear under various names: “Madonna and Child,” or more distinctive titles like “La Belle Jardinière” (“The Beautiful Gardener”) by Raphael, which I would come to find particularly moving.