Language

How Words Influence Us

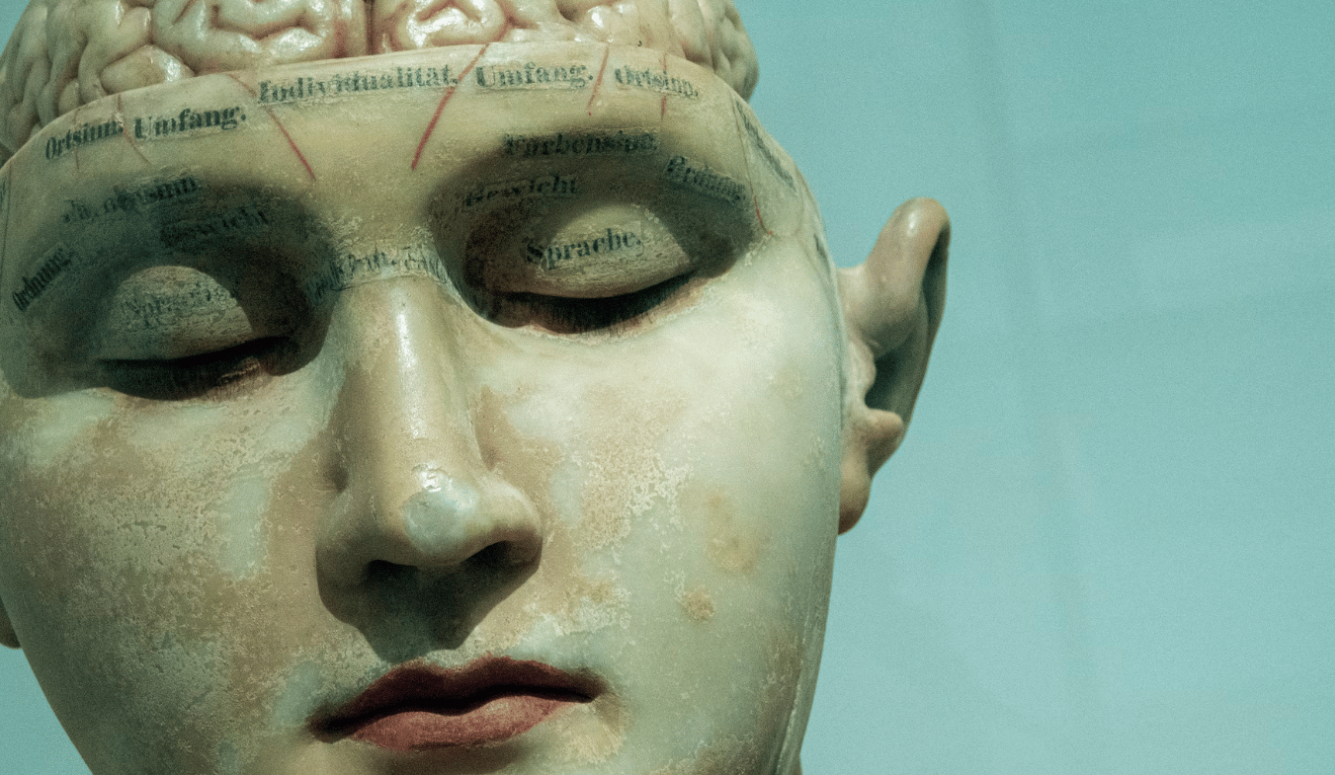

With its thousands of problem-solving, information-discarding, thought-terminating conventional categories, a language is a great collection of off-switches for the mind.

Reality matters because our survival depends on it. To navigate reality, as individuals, we first reduce its complexity through the interface of sensory perception. But to coordinate around reality, in concert with other people, our species’ forte is to add another interface, a further level of transformation: the interface known as language. We present reality to each other in language-delineated pieces. As the mathematician Friedrich Waismann said, language is the knife we use to cut out facts. And like any knife, language is both destroyer and creator. We do not coordinate around reality but around versions of reality hewn by words. The result is awkward for the scientist but convenient for the lawyer.

A problem is that we naturally take our word-given versions of the world to be reliable. And when we feel that we understand something clearly, this has a thought-terminating effect. As the philosopher C. Thi Nguyen puts it: “A sense of confusion is a signal that we need to think more. But when things feel clear to us, we are satisfied.” This creates a kind of cognitive vulnerability that allows people to be manipulated by any system of thought that is “seductively clear.” As specific examples of such systems, Nguyen discusses conspiracy theories and bureaucracies. But I argue that language itself is one such seductively clear system. In fact, it is the seductively clear system, with its thousands of problem-solving, information-discarding, thought-terminating conventional categories. A language is a great collection of off-switches for the mind.

In a world that desperately requires wisdom at all points, we have a duty to know and understand how language works, both on others and on ourselves. We have a responsibility to be mindful of how our choices manipulate people’s attention, channel or terminate their thinking, and implicate them in joint commitments. And when we hear the things that others say, we need to be mindful of their goals and motivations, which underlie their choices to use certain words and not others. If their words invite us to subscribe to some linguistic version of reality, we must ask: Why this map and why those landmarks? What are this person’s reasons for saying that, and for saying it like that? How else could it have been said? In the mercurial cartography of language, we need to remember there is a real terrain beyond the maps.