Art and Culture

Boring Art, Impotent Politics

Mixing aesthetics and activism does a disservice to both.

I think public art is propaganda, frankly.

~Hank Willis Thomas, 2019

In 2019, Brooklyn-based multimedia artist Hank Willis Thomas was awarded a commission to create a sculpture celebrating the civil-rights icon Martin Luther King Jr. The monument was to be installed on Boston Common, America’s oldest public park, where King gave a speech to a crowd of 22,000 people in April 1965. Thomas was among five finalists out of 126 applicants whose work was reviewed by a committee convened by the City of Boston and the non-profit Embrace Boston. The non-profit’s stated mission is “to dismantle structural racism through our work at the intersection of arts and culture, community, and research and policy.” In the section dedicated to “arts and cultural representation” this goal is further specified as:

Activate arts and culture to reimagine and recast cultural representations of language, images, narratives, and cognitive cues to interrupt and reimagine the public’s conventional wisdom about race in which White privilege and racial disparities are perceived as normal and disconnected from history and institutions. [emphasis in original]

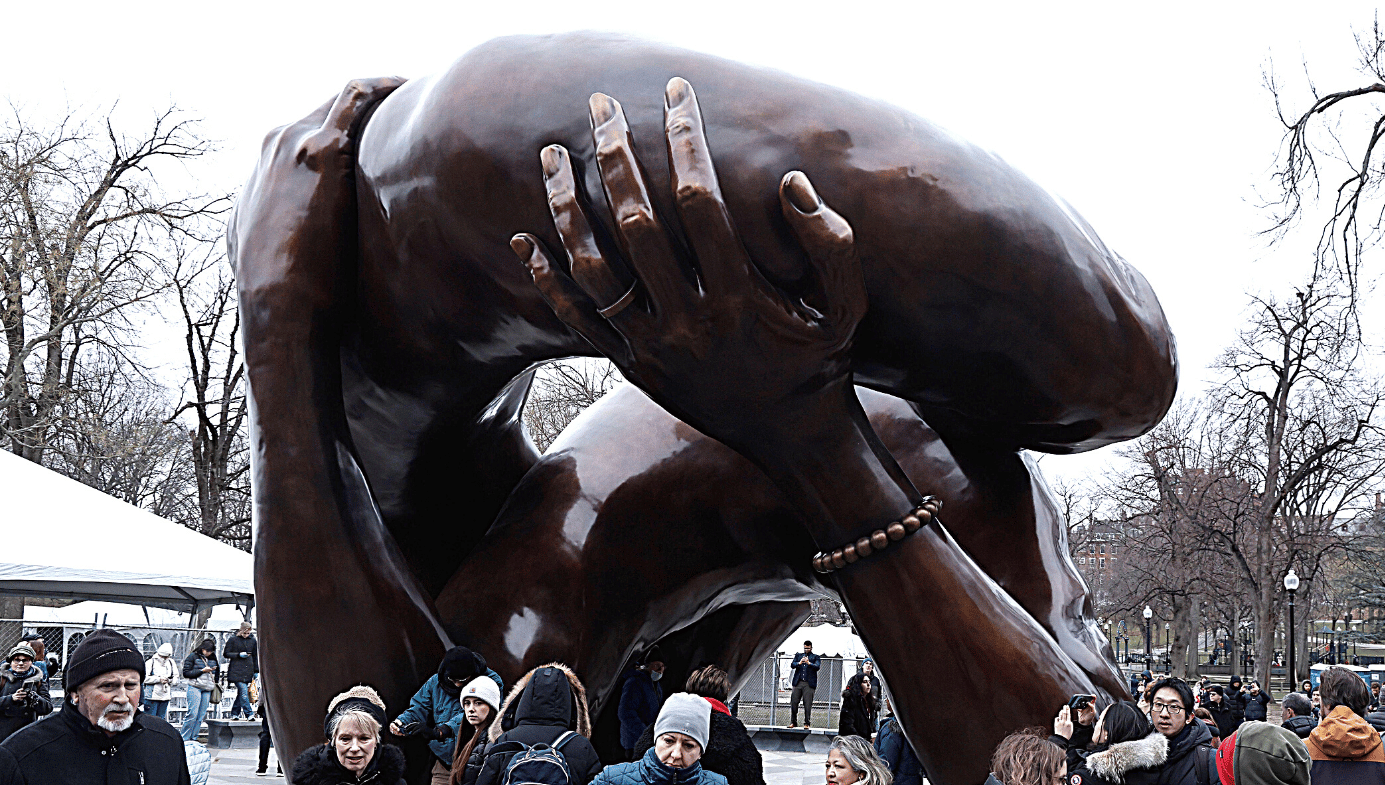

At first glance, the sculpture made possible by Embrace Boston, also serendipitously titled ‘The Embrace,’ seems perfect for recasting cultural representations. The monument is based on a 1964 photo of a celebratory hug shared by King and his wife after he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. Had Hank Willis Thomas gone down the well-trotted path of figuration—providing a portrait likeness of his subjects—‘The Embrace’ would have been treated as any other dignified public sculpture project, garnering complimentary mentions and perhaps some accolades, that rubbed off the memory of MLK onto his bronze avatar. But the artist, who came to sculpture from photography, and whose other work emphasizes concept over form, chose an approach that eschewed figuration. The Boston sculpture presented emblematically posed, disembodied extremities (no heads, no torsos) intended to convey an idea not through representation, but through a symbol of love.

Hank Willis Thomas had already tested this model, most recently in ‘Unity’ (2019)—a pedestal-less, bronze, 20-foot-tall arm, amputated across its rotator cuff and planted on the cement divider at the foot of the Brooklyn Bridge, its index finger raised to the sky. It has been favorably received. The latest 20-foot-tall monument, which reportedly cost $10m of private funding, was finally unveiled on January 13th, in front of local dignitaries and MLK’s son Martin Luther King III. While the reaction on the scene was celebratory, social media erupted with a panoply of jokes, most of which zeroed in on the sexual associations prompted by the tangle of intertwining limbs.

In 2019, Hank Willis Thomas unveiled “Unity,” a sculpture in @DowntownBklyn commissioned by our #PercentforArtNYC program. Towering bronze sculptures, “The Embrace” and “Unity” both personify the incredible impact of solidarity and community empowerment. pic.twitter.com/cb3wrgFrBH

— NYC Cultural Affairs (@NYCulture) January 16, 2023

The uproar was impossible to ignore. The website Hyperallergic—a bastion of progressivism—ran an article titled, “The New MLK Sculpture Is Officially a Meme,” highlighting noteworthy responses from Twitter and TikTok. The sculpture was also the subject of a brutal routine by the comedian Leslie Jones on The Daily Show:

Many other commentators also noticed the sculpture’s unmistakable (and surely unintended?) sexual imagery, pointing out that it resembled an engorged penis held by dainty female hands and/or cunnilingus performed by a bald man, but they were not amused nor did they mean to be amusing. The Washington Post columnist Karen Attiah posted a string of searing tweets, calling out those behind the sculpture for reducing King and his wife to body parts and grossly distorting “his radicalism, anti-capitalism, his fierce critiques of white moderates” in a “whitewashed symbol of love.” She followed up her thread with a strongly-worded opinion piece in which she described the sculpture as a “half-assed banalit[y] in the name of ‘social justice.’”

It doesn't sit well with me that Martin Luther King and Coretta Scott King are reduced to body parts-- just their arms. Not their faces- their expressions.

— Karen Attiah IS ON INSTAGRAM @karenattiah (@KarenAttiah) January 16, 2023

For such a large statue, dismembering MLK and Coretta Scott King is... a choice. A deliberate one. pic.twitter.com/Asi0SCHtPg

The following day, Coretta Scott King’s cousin, Bay Area activist and community organizer Seneca Scott, took the condemnation a step further in an article titled “Masturbatory ‘Homage’ to My Family.” Referring to the sculpture as a “major dick move (pun intended) that brings very few, if any, tangible benefits to struggling black families,” he derided it as “performative altruism” meant to “represent black love at its purest and most devotional.” This, he argued, played into a “classist and racist … woke algorithm.” Far from being a proper celebration of an icon, “this sculpture is an especially egregious example of the woke machine’s callousness and vanity.” For Scott, the disembodied, sexually suggestive bronze unveiled on Boston Common was yet another example of blaxploitation.

All this criticism arises from the simple fact that the monument is visually unintelligible. While Thomas’s 2019 ‘Unity’ benefits from the intrinsic likeness of a vertically placed human limb to the time-honored obelisk shape, ‘The Embrace’ is fundamentally confusing. It is not easily legible, forcing the viewer to deduce meaning in the absence of relevant components (such trifles as heads and faces). Its references are muddled. It takes for granted the premise of Gestalt psychology, which states that the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. ‘The Embrace’ certainly does not make it easy to get past the parts.

If the German psychologists who formulated the principles of Gestalt were correct, if our minds do indeed have a tendency to rely on visual clues to interpret an image, then formal clarity and cohesion become paramount. Otherwise, we end up with an interpretational free-for-all, a Rorschach test that allows the audience to exercise their debauched imaginations. In a television interview addressing public response to the sculpture, Thomas himself brought up the idea of the sculpture as a Rorschach test. He suggested that the audience’s collective mind is in the gutter, but failed to acknowledge his responsibility for the visual ambiguity that caused the reaction. It is the sculptor’s job to design a work that enables viewers to deduce its overarching meaning, without ending up in interpretational cul-de-sacs.

Consider two historic examples of successful sculpture that share meaning (love) and appearance (the organic shape) with ‘The Embrace.’ The first is an intimately sized (under two feet) limestone carving by the French-Romanian sculptor Constantin Brancusi. ‘The Kiss’ (1916) shows a naked man and a woman locked in an amorous embrace. The front of their faces and their mouths are hidden from view. Their respective genders are identifiable only by the relative lengths of their hair and the female figure’s flattened breasts.

The lovers’ anatomically improbable square profiles, complete with half-exposed stylized eyes, merge into a single frontal view, making the idea of the embrace, and the kiss itself, unambiguously central. Indeed, Brancusi’s little sculpture would make a splendid symbol of Unity Through Love.

The second example is the ‘Recumbent Figure’ (1938) by the English sculptor Henry Moore. Carved from stone mined in Oxfordshire, this mid-size sculpture, which represents a female nude, reinforces the idea of an organic mass through the way the body is posed, its resemblance to bleached bones and skulls, the rounded shapes of Moore’s native landscape, and modernist nods to both ancient and indigenous predecessors. Its overarching message of natural harmony uncorrupted by technology supersedes the separate visual components.

As in the case of Brancusi, the dirtiest of minds would struggle to come up with an obscene reading. Both sculptures make self-evident the ideas they visually represent.

Unlike these two works, however, ‘The Embrace’ is a muddle of the inexplicable. It is selectively representational, showing isolated hugging arms cropped from a photograph in which the facial expressions were central. The chart of the arms is meaningless without the legend needed to explain the nature of the hug (support, pride, joy), and this opens the awkward tangle to arbitrary interpretation. In the absence of heads and faces, the arms retain sartorial identification—a bracelet on the bare forearm of Coretta Scott King and the shirt and suit of the arm of the MLK. But this only further lends the sculpture to sexualized readings, prompted by a slender female arm supporting a plump, elongated male appendage, and turns what was intended to be a respectful work into a bad joke.

It also makes the sculpture visually proximate to an intentionally humorous work by the Los Angeles-based veteran of conceptual art, Paul McCarthy. In 2007, McCarthy created a monumental, multi-part, inflatable sculpture that realistically represented a large pile of excrement. Appropriately titled ‘Complex Shit’ (later demurely renamed ‘Complex Pile’), it was McCarthy’s commentary on public sculpture’s tendency to pretension.

‘Complex Shit’ garnered additional notoriety in July 2008, when its original incarnation, on display at the Paul Klee Center in Berne, was caught in a strong gust of wind and carried over 200 meters, landing on the grounds of a children’s home. For someone making a public sculpture in the late 2010s, it must have taken some chutzpah (or ignorance of conceptual sculpture) to attempt a bronze, organically shaped, multi-part monumental form and assume they would escape association with McCarthy’s shit.

Are these multiple formal shortcomings the result of ineptitude? Hard to say. It may just be a case of misplaced priorities. In an Artnet interview from the summer of 2020, Thomas argued for the unreserved inclusivity of an artist’s self-designation: “Well, I think we’re all artists.” Which makes his following statement about not appreciating or respecting art until “about the age of 30 … by that time I already had a BFA and an MFA” either disingenuous or seriously misguided. It is hard to imagine a successful application for a Bachelor of Fine Arts, not to mention a Master of Fine Arts degree, which openly admits the applicant’s lack of appreciation or respect for art.

Meanwhile, Thomas’s relationship with progressive politics is unambiguous. In response to a question about “changing unjust institutions with non-art work,” he describes founding a Super PAC (later a non-profit called “For Freedoms”) as a way “to promote the critical work artists are doing by framing political speech, because we know that when you say something is ‘political’ it implies there’s something at stake.” In other words, politicization is a public relations strategy. Asked whether he would entertain the idea of going into politics, Thomas responds: “I think anyone who cares at all should consider it. I would hope that I am not the only artist who’s seriously considering it, and will probably at some point try to run for some office.” It is surely a better stratagem to enter politics directly, rather than attempt to create a space for politics in art. Otherwise, we end up with boring art and impotent politics.

This was precisely the argument advanced nearly half-a-century ago by the influential New York art critic Clement Greenberg. In a 1976 lecture to a packed room of artists and students in London, Greenberg brought up the (then) current fashion for politically committed art. In his view, prioritizing political content over form tended to diminish the quality of the work. Art, he argued, was being taken “in the direction where presumably taste could not follow … where the eye could not follow…” This point was consistent with Greenberg’s position that the source of art’s power is its “self-critical” quality, whereby each medium is expected to function according to its own unique method (painting is distinguished by its flatness, for example).

According to Greenberg, when the content takes over, and the medium loses its purity, the result is a paltry artwork that could only fool an audience outside its respective field:

You wrote bad prose, but you’re read by artists who could not tell the difference between good and bad prose, you wrote incoherently, but you are not being read by logicians, you did a pastiche of philosophical language, but you are not being read by philosophers.

Greenberg’s assertion that a failure to distinguish categories is detrimental to both art (the form) and the political message (the content) is very much applicable to our current predicament. Foreshadowing the mockery elicited by the representational ineptitude of ‘The Embrace,’ the critic pointed out: “It’s very easy to make fun of these things because they deserve to be made fun of, and it’s very easy to laugh at them because they deserve to be laughed at because they are so boring.” In his view, art and politics simply do not mix, and attempts to force them together reduce the efficacy of both.

What should politically active artists do then? Greenberg expanded on his position in the Q&A session, where he encouraged a direct engagement with politics outside of one’s art:

When you are making an art, you are trying to make good art, just as when you are making a screwdriver, you are trying to make a good screwdriver. If you care about what’s happening in the world, you don’t retreat to your studio and try to make art, you go out and try do something about it. […] What I infer from what you said about those people caring what happens outside your studios, outside of art galleries, outside museums, outside art … if you care about these things, you go outside and try to do something about it, if you care enough.

The artist’s mandate is to make art driven by aesthetic concerns, not political aspirations: “Most of us, we care some, but we are supposed to make screwdrivers, so we make screwdrivers … and we don’t have time left for anything except to join a trade union … or maybe go on strike. We certainly don’t do social work.” And while Greenberg recognized that “there are more important ends in life than art” he maintained that an artist’s only aspiration should be to “make the best art.” As a writer himself, Greenberg believed his energy was best spent on writing, not social activism: “the world is full of pain and something that should be done about it. I am not doing a damn thing about it, and I am not proud about that, but I choose not to do anything about it because I only have one life to live. And don’t find it interesting to go out there and help the suffering and the poor.”

Greenberg positively flaunted his lack of political commitment. His anachronistic rational egotism allowed him to embrace his self-interest openly, but his self-interest was in being a writer and not a social worker, as he put it. Such an uber-formalist attitude would not pass muster in today’s art world. Political neutrality is no longer a viable option. Yet, the critic got one thing right when he refused to reduce art to agitprop. In response to further probing, Greenberg bluntly stated that those who make political art “contribute neither to politics, nor to art … neither politics nor art have received anything from the elucubrations of these people.”

The furor around ‘The Embrace’ seems to support Greenberg’s case, but this time the judgment does not come from the ivory tower, but from the audience pit. The wider public—with its innate suspicion of the art world’s insider trading and the baffling price tags of public sculpture—can be relied upon to voice their opinion that the screwdriver they were presented with on Boston Common is no good, and their feedback turned a monument to one of the 20th century’s greatest men into a meme. The public’s response is genuine, heartfelt and—given its provenance—cannot be blamed on elitism. The vox populi’s verdict will stand because, as Thomas correctly stated in his 2020 interview: “Public space belongs to the public and they should have a say in what kinds of images and objects represent the society.” The 20-foot-tall Rorschach test that is ‘The Embrace’ proves that our society, for all its faults and shortcomings, is not ready to be represented by a meme. At least not yet.