How Do We Protect Ourselves from Billion-Dollar Boy-Men?

The hubris and dilettantism of corporate titans is an old story. But the risk has been compounded by digital technology’s hugely scalable nature.

When Hollywood gives us the inevitable biopic about Sam Bankman-Fried and the collapse of his FTX cryptocurrency exchange, it’ll be interesting to see whether even skilled filmmakers are able to convincingly portray Bankman-Fried as any kind of compelling villain figure. FTX’s 30-year-old founder has admitted to many mistakes. But while his operations are now being investigated by the Securities and Exchange Commission and Justice Department, there isn’t yet any evidence that he’s committed a crime. His sins, rather, seem to be those of a distracted young dilettante who was in over his head, and who never fully realized that running a $32-billion company operating in a volatile financial sector is a full-time job.

Bankman-Fried fashioned himself a lobbyist, not only on behalf of FTX, but also the crypto industry as a whole; became deeply vested in an array of ambitious philanthropy projects; spent a lot of time tweeting and giving interviews; and, crucially, continued to build out his original trading firm, Alameda Research, in parallel with FTX. Ultimately, it seems to have been the Alameda anchor that dragged down the FTX ship.

CoinDesk spoke to several current and former @FTX_Official and Alameda employees who agreed to talk on the condition of anonymity.

— CoinDesk (@CoinDesk) November 12, 2022

“The whole operation was run by a gang of kids in the Bahamas,” a person familiar with the matter said.https://t.co/nO5n2bOuc7

According to an investigative report by David Yaffe-Bellany of the New York Times, based on interviews with Bankman-Fried’s subordinates and confidantes, the commercial operations of FTX and Alameda were promiscuously intermingled. Alameda has been run by a former trader named Caroline Ellison, a one-time romantic partner of Bankman-Fried. And according to Yaffe-Bellany, “a guest who visited FTX’s complex in recent months said Ms. Ellison had been sitting within view of computers displaying [FTX’s] trading data.” By design, the structure of Bankman-Fried’s operations blurred the usual lines that separate professional and personal spheres, with the entire FTX senior brain trust living, working, and often dating within the same isolated Bahamas resort compound.

For techno-futurists who see the dot-com billionaire class as offering deliverance from snobbish, bureaucratized business culture, this kind of work environment no doubt sounds idyllic. (If nothing else, the film version of Bankman-Fried’s odyssey will have gorgeous sets.) Here you had a group of young, teched-up globetrotters building the financial architecture of the future in T-shirts and cargo shorts. For these overlords of global crypto, national laws and boundaries held little meaning: When Bankman-Fried found US regulatory laws too stifling, he took off to Hong Kong, before then deciding that he liked the West Indies better.

And since crypto is a completely virtual asset whose value is secured by literally nothing except a set of mind-bending cryptological algorithms, Bankman-Fried had no supply chain to worry about, no labour unions to negotiate with, and no warehouses full of inventory. Between FTX and Alameda, Bankman-Fried and his sometimes girlfriend never had more than about 350 employees working for them—about the same number you’ll find working at a single Walmart Supercenter. It was, in other words, the ultimate laptop-class gig.

This geographically deracinated, highly mobile corporate model is characteristic of the crypto industry as a whole, whose pioneers exude a pronounced skepticism toward not only the legacy banking system, but also the checks, balances, oversight mechanisms, and reporting requirements that circumscribe its operations. Putting aside whether the dream of challenging (let alone overturning) the hegemony of fiat currencies is possible (or even desirable), FTX’s fate shows that all those mundane legal, regulatory-compliance, and human-resources strictures have their benefits. It’s one thing to create a set of currencies modelled on a purely libertarian ethos, and another thing to create corporate organizations in that same image. An algorithm can be perfected, or at least programmed in a way so as to automatically course-correct. But not so a human being.

In the case of FTX, one benefit of traditional oversight mechanisms would have been having someone in the Bahamas who was ready and able to blow the whistle on dubious related-party transactions of the type that Bankman-Fried is alleged to have used to bail out Alameda with FTX assets. Bankman-Fried had great trust in his own counsel (he reportedly doesn’t even read books), and largely confined his interactions to a tiny group of loyal subordinates whose gilded lifestyles flowed from his patronage. Not surprisingly, no one within that entourage was able to successfully press him on warnings that his empire had become financially unstable.

The hubris and dilettantism of corporate titans is an old story, of course. But the risk has been compounded by digital technology’s hugely scalable nature. In the industrial age, an entrepreneur with a groundbreaking idea—say, for a revolutionary form of plastic injection moulding, or a new pharmaceutical product—would typically have to spend years in a lab, construct pilot projects, apply for patents, proselytize at trade shows, recruit skilled engineers, and find distributors, all before making a single sale. Even with the benefit of computer-assisted design, it still typically takes four years for even an established car company to get from concept to showroom. But an algorithm for exploiting inefficiencies in the crypto markets, of the type Bankman-Fried began implementing as early as 2018, at age 26, can go from Reddit-thread musings to profitable implementation in a matter of hours. The career arc of moguls from the industrial age often followed the natural working lifespan of their primary capital assets, such as blast furnaces, kilns, railroads, and automotive plants—which is why so many of these figures remained relevant well into their senior years. In the digital age, on the other hand, whole boom and bust cycles can play out while magnates are in still in their 20s.

Moreover, the traditional process of building out an industrial operation typically has required that entrepreneurs partner with bankers, investors, lawyers, and auditors, all of whom exert a naturally conservative influence on operations. In many cases, the capital costs and other barriers to market entry are so high that entrepreneurs sell out to established operators, or at least stock their boards of directors with third-party representatives. But the fact that crypto and other digital enterprises can be scaled instantly and globally with minimal capital investment allows entrepreneurs to avoid all of these influences—thereby allowing them to exist as superannuated adolescents from out of an Adam Sandler movie, often cloistered within tiny peer groups consisting of similarly naive brainiacs.

The other aspect of digital culture that can enable plutocrats to act impulsively is the protective presence of network effects. Elon Musk, though no youngster, can act like one at Twitter because he knows that millions of users are locked into his product thanks to our painstakingly built-up network of friends, contacts, and commercial partners: A mass exodus to a competing product (say, Mastodon) will be inhibited by what’s known as the collective-action problem. This fact helps explain why so many business journalists remain darkly fixated on Musk’s behavior at Twitter, despite the company’s relatively small economic footprint. The embittered tone of their reporting reflects their resentment of Musk’s power over our professional subculture, and the guilty knowledge that we further enable him with every tweet we send—including those tweets denouncing Twitter itself.

Imagine an alternate universe in which Musk’s corporate path were reversed—i.e., that he were now purchasing Tesla with the tens of billions he’d earned by founding Twitter, instead of vice versa. Under this thought experiment, would Musk dare fire half of Tesla’s engineers during his first month on the job? Or signal his contempt for large swathes of Tesla’s customer base? Nothing like this would ever happen because cars are largely fungible goods, with few barriers to product switching. And a meltdown at Tesla would simply drive consumers to other brands.

There’s no easy fix to any of these problems except at the level of consumer behaviour. The people most beholden to Twitter’s network effects are those power users who rely entirely on Musk’s service to connect with the world, and so cannot even imagine a Twitterless universe. The reality is that Facebook, LinkedIn, Substack, TikTok, Instagram, YouTube, and a dozen other services all can be used in ways that mimic Twitter’s best features—content sharing, professional self-promotion, and social connectivity—with less of Twitter’s toxic side effects (shaming, mobbing, and ideological self-segregation).

None of these social-media services, standing alone, offer a full replacement for Twitter. But then again, one of the lessons of this Musk moment is that it’s dangerous to rely on any social-media service as a one-stop shop: Even if Musk sold off Twitter tomorrow, who’s to say that the next owner would be any less impulsive and volatile? In the long run, the only way for users to avoid being held hostage by mercurial digital overlords is to start treating social media services like any other consumer good (or professional tool) that exists within a competitive marketplace—which is to say, something we consume more or less (or none) of, depending on how its costs and benefits stack up to rival offerings.

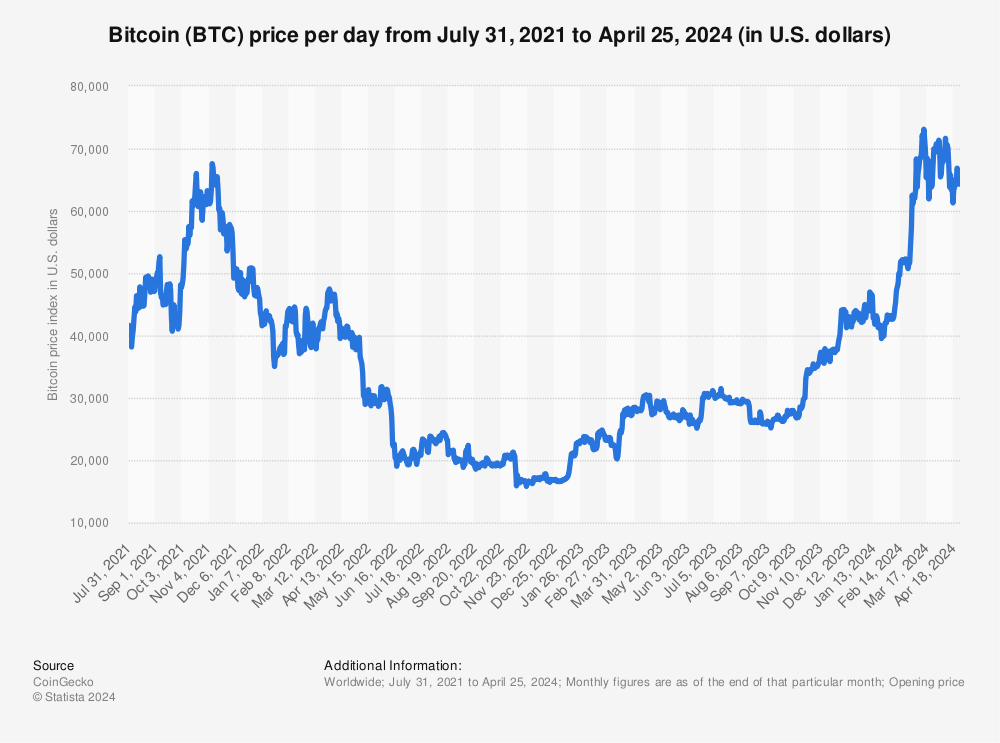

When it comes to FTX, and crypto more generally, the lesson for consumers is even more basic. Indeed, it hearkens to one of the very first things that high-school students learn in their introductory economics courses—which is that money has multiple distinct functions, including both medium of exchange, and store of value. The fact that crypto has shown itself to be a genuinely revolutionary medium of exchange seems to have led many enthusiasts into the completely unrelated belief that it must also work well as a store of value. But as any 2021-era Bitcoin investor can attest, it’s not. Surely, a good rule of thumb is that one should think twice before investing in any asset with no intrinsic worth, and whose value rises and falls based on billionaire Twitter feuds and the daily Discord banter of fanatical crypto bros.

Find more statistics at Statista

History is littered with asset bubbles and market manias. And those who’ve been stripped of their FTX assets, or victimized by the “crypto winter” more generally, are in good historical company. There’s no shame in it. In fact, it’s important to remember that some of the same media outlets now casting crypto as a Ponzi scheme and Bankman-Fried as a likely fraud were, just a few months ago, inflating his reputation as a boy wonder and even a potential industry saviour.

The lesson here is not that crypto users are all suckers, much less that “You Can Forget About Crypto Now,” as one provocative Atlantic headline put it. It’s that even those of us who continue to use crypto for certain kinds of financial transactions shouldn’t be using it as a repository for our life savings. If there’s some way to put that message at the heart of the Bankman-Fried biopic that’s no doubt coming soon to a theater near you, it’ll be a film very much worth watching.