Benito Mussolini and the Fascist Love Affair with Soccer

Embracing a sport that combines nationalism, mass spectacle, and physical refinement, Il Duce set out to make Italy a World Cup champion.

Like most politicians of his time, Italian fascist dictator Benito Mussolini knew soccer mostly as an adult. At the time of his birth in 1883, the sport was played in Italy only by British sailors who docked their ships in the ports of Genoa, Palermo, and Naples. The first local club created exclusively for soccer, Internazionale Football Club Torino, wasn’t founded until 1891. The first “official” match, between Genoa Cricket and Football Club and Football Club Torinese, wouldn’t take place for another seven years. Most of the physical activities that were practiced on the peninsula at the end of the 19th century, like boxing, shooting, or fencing, were related more to the preparation of one’s body for war (or duels) than to playful or sporting endeavours.

Mussolini’s own connection with sporting disciplines, such as rugby, tennis, skiing, swimming, and cycling, seems to have been related more to physical conditioning than recreation. He was a robust but short man, barely five-and-a-half-feet tall, and several of his biographers suggest that he exercised so as to maintain a bearing that would facilitate success in his favourite game: seducing women. (It is said that he had hundreds of sporadic lovers, and even some official ones, including Clara Petacci—whom he would die with in the closing days of World War II.)

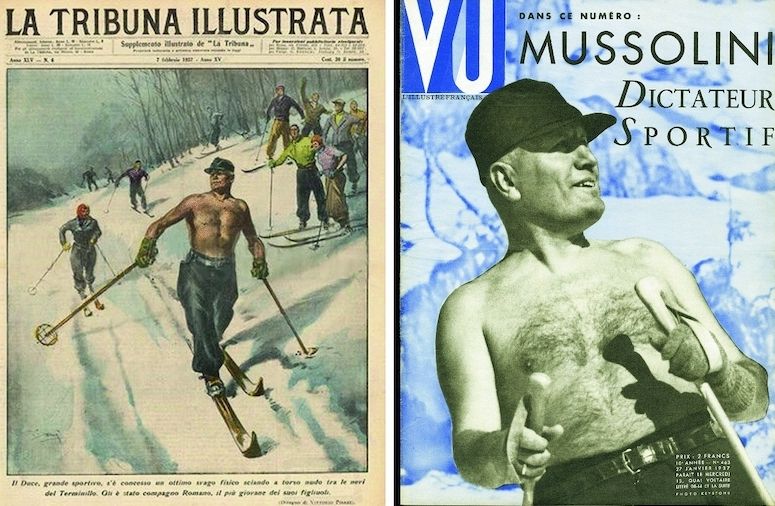

British historian Christopher Duggan, the author of several books about Mussolini, notes that Italian fascism, like other national variants, was characterized by a “cult of the leader,” and that Il Duce was portrayed “as a kind of superman: virile, athletic, a great sportsman.” Numerous films and photographs showed him bare-chested, even when skiing on snowy hills. The obsequious journalist Adolfo Cotronei, deputy director of the sports newspaper La Gazzetta dello Sport in the 1920s and 1930s, described Mussolini as

a man of sport in the highest sense, because his physical life and moral life harmonize and they complement each other wonderfully. His torso is powerful, his arms athletic. He seems made to break and crush. In the face of this exuberance of muscles and nerves, in the face of that Herculean solidity, our imagination stops. We feel that no one can beat him, that no one can compare with he: giant among the pygmies.

Mussolini warned that physical activity among children and adolescents, long ignored and shunned by Italian royals and socialists alike, was largely absent from school curricula. In keeping with the fascist belief that personal well-being is a social duty, state officials instructed Italian educators to expand physical-activity programs.

Soccer grew in popularity more than other sports and pastimes due to its simplicity. The ball, made of leather or home-made with scraps of cloth, old stockings, or pieces of rubber, could be kicked with the same shoes worn to school or mass. Games could be held not only indoors at educational institutions, but also in public squares and empty fields after school, with intense contests often lasting late into the night.

Some adults liked to play, too. But what most adults really enjoyed was the experience of watching others play. Il Duce soon realized that this “insignificant game,” as he’d once called it, had become a social phenomenon—one that aroused ardent passions among the masses without going through the worn fabric of the army or church.

Infused by local and regional loyalties, soccer contributed to the creation of a collective Italian identity—while also sometimes exacerbating (politically useful) antagonisms. The fascio littorio, from which originated the name of the National Fascist Party in Italy (and the term “fascism” itself), depicts many thin rods tied together in a bundle, thereby attaining strength through unity of purpose. Soccer seemed to offer a symbolically similar concept, with 11 men all cooperating to get the ball into an opponent’s goal.

In his book Sport e fascismo: la politica sportiva del regime, 1924-1936, Felice Fabrizio wrote that “Italy was the first state, together with the Soviet Union, to organize [an explicit] policy that would lead the country to become a sports nation.” In this regard, Mussolini’s plan began with the promotion of new soccer clubs and huge stadiums across Italy. Under the terms of a 1926 charter known as Carta di Viareggio, moreover, the country’s elite soccer tournament ceased to be a showdown between the North and South groups, and instead became a contest that gradually incorporated matches between clubs from different regions. In 1929, the Serie A (first division) and Serie B (second division) were formed, a system that evolved into the framework that still exists today.

Mussolini’s second step was global in nature, with Italy vying to host the inaugural World Cup soccer tournament in 1930. However, his aspirations were thwarted by Uruguay, whose candidacy was supported by South American neighbours. When that tournament took place in Montevideo, Italian officials declined to participate, citing logistical concerns.

The truth was that Mussolini didn’t want to risk sending a team that would lose. Italy had just lost a semi-final match to Uruguay at the 1928 Olympic tournament in Amsterdam. Under advice from team coach Vittorio Pozzo, the Italian leader preferred to wait for the second iteration of the World Cup in 1934.

The disdain with which the Italian government treated the inaugural World Cup in Uruguay would be reflected in La Gazzetta dello Sport, which was closely linked with Mussolini’s fascist regime: The newspaper barely reported on the tournament, devoting only about 20 lines of coverage to the entire event.

In its aftermath, Italy fought hard to play host in 1934. The president of the Italian Football Federation (Federazione Italiana Giuoco Calcio, or FIGC), Giorgio Vaccaro, launched the country’s bid at the International Federation of Association Football (FIFA) congress in San Remo. In a world still being crushed by the Great Depression, the Italians had only one rival: Sweden. Two months later, the Swedes withdrew their application without offering any official explanation. (It’s suspected that they expected to lose the vote decisively, with the Italians having sewn up a majority of national delegates.)

Italy promised an over-the-top tournament. Unlike the Uruguayan championship, which had been played entirely in just one city, the 1934 version would be played in eight locations—Rome, Milan, Bologna, Turin, Trieste, Genoa, Naples, and Florence. Three venues built by the Mussolini regime before 1930—Stadio Nazionale del PNF in Rome (whose name translates to National Stadium of the National Fascist Party), the Litorialle in Bologna, and the San Siro in Milan—were joined by Florence’s Giovanni Berta stadium in 1931, the Littorio of Trieste in 1932, and Turin’s Stadio Comunale Benito Mussolini in 1933. Likewise, the Partenopeo in Naples and the Luigi Ferraris in Genoa were expanded and modernized.

When Giorgio Vaccaro, the FIGC president, met with Mussolini to officially inform him that Italy would host the second World Cup, the following dialogue reportedly occurred:

Italy must conquer the championship.

Of course, Duce. We will do our best.

You didn’t understand me, Vaccaro. Italy must win. This is an order.

Did this conversation actually happen? It seems unlikely. But, fact or fantasy, the “order” was carried out. This was accomplished in part by recruiting South American footballers of Italian origin, a practice in keeping with the regime’s focus on the link between Italian blood purity and citizenship. (“Behind the athletic victory shines the victory of the race,” said journalist Bruno Roghi, director of La Gazzetta dello Sport.) Although the eastward migration of Argentine and Uruguayan amateur players to the main Italian teams had begun a few years earlier, the process intensified after the 1930 World Cup. Héctor Scarone (who landed with the Lombard club Internazionale Milano), Pedro Petrone (to Fiorentina), and Ernesto Mascheroni (to Ambrosiana) are among those who crossed the Atlantic Ocean to become world champions. Not only did such players help boost the Italian squad, their departure from South America weakened the Italians’ most powerful rivals.

Another step toward Italian success involved the qualifying process. Italy had drawn Greece as its opponent for a pair of home-and-away matches. On March 25th, 1934, two months before the start of the World Cup, the Italian national team easily beat the Greeks 4-0 in Milan. But the rematch, which was supposed to take place in Athens, was never played. At the time, it was reported that the Greek team, overwhelmed by the wide margin of victory in the first meeting, was unwilling to endure a second humiliation, least of all on their home turf. But six decades later, journalists revealed that the then-impoverished Greek soccer federation was gifted a two-storey house in Athens as a site to establish its headquarters. Who paid for it? Reportedly, it was Italy’s governing soccer body.

Even in its first (and, as it turned out, only) match against the Greeks, the victorious Italian squad included three players who, according to then-applicable rules, weren’t entitled to play. Although the regulations allowed that “players capable of representing several National Federations” (i.e., those with double nationality) could choose which country they played with, the rules also required that if a footballer wanted to transfer from one national affiliation to another, he first had to live a minimum of three years in his newly designated homeland, and a similar period since his last game with his old team. Neither the Argentines Luis Monti and Enrique Guaita, nor the Brazilian Amphiloquio Marques (listed as Anfilogino Guarisi, employing the surname of his Italian mother Wanda), met those requirements. (Monti had played for Argentina on July 4th, 1931, against Paraguay. Guaita had played against Uruguay on February 5th, 1933, just one year before the match with Greece. Marques-Guarisi had emigrated to Italy in July 1931.)

Days before the start of the 1934 World Cup, Mussolini met with Vittorio Pozzo. Several sources agree that, during the meeting, Il Duce warned the coach: “You are solely responsible for success, but may God help you if you do not win.”

The threat was also extended to Pozzo’s players, who’d been forced to join Mussolini’s National Fascist Party. During a meal supposedly served to forge “camaraderie,” Mussolini addressed them. “Win or shhhh,” he said, as he made a slashing motion across his throat. Fortunately for the players, they did win, beating Czechoslovakia in the final match by a score of 2-1 at the Stadio Nazionale PNF in Rome.

Adapted, with permission, from the forthcoming Sutherland House book, Dark Goals: How History's Worst Tyrants Have Used and Abused the Game of Soccer, by Luciano Wernicke. Copyright © 2022 by Luciano Wernicke.