The World Economic Forum and the Misleading Politics of Gender Equality

Women fall behind in countries with low levels of economic and social development, largely due to poor educational opportunities.

The annual release of the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Index (GGGI) often provokes consternation and lamentations among journalists, politicians, and activists about the supposedly sorry position of women in the world today. According to the most recent GGGI report, and due in part to the effects of COVID-19 on women’s employment, “Another generation of women will have to wait for gender parity.” Time magazine uncritically repeated the report’s conclusion, noting that “it will take an average of 135.6 years for women and men to reach parity on a range of factors worldwide, instead of the 99.5 years outlined in the 2020 report.” A more strident example is provided by an opinion piece in the Sydney Morning Herald that excoriated Australians for their ongoing mistreatment of women:

This failure of policy reflects government indifference to the fact that Australia is a society in which women are actively marginalised and held back. Perhaps the most telling statistical outcome from the 2021 GGGI is that Australia ranks equal first for educational attainment among women and girls, but 70th for economic participation and opportunity … The state of gender equality in Australia is, put simply, shameful. And it’s getting worse, at a rapid pace.

The truth is that the GGGI is, at least in part, a political wish-list for some gender activists; for instance, focusing on women’s relative to men’s economic accomplishments even though it is only a priority for a minority of women.1 The measure focuses on gaps in women’s and men’s outcomes in certain domains of life, including educational, heath, economic participation, and political representation, and rank orders nations on the magnitude of the gap. So, if a nation has 100 parliamentarians and 75 of them are men and 25 are women, then that country’s rating for this aspect of political representation will be 0.33 (i.e., 25/75). The 135.6 years away from gender equality is an extrapolation based on a slightly positive trend line for overall change across these four domains and represents when the line will hit the zero-gap mark. Extrapolating out by more than a century based on a small positive trend is statistically meaningless, but it does create attention-grabbing headlines and foster a sense of urgency. In fact, the gap will never actually close, in part because it is designed to make equality (by their definition) difficult to achieve. As the authors of the 2021 report explain:

The index rewards countries that reach a point where outcomes for women equal those for men, but it neither rewards nor penalizes cases in which women are outperforming men in particular indicators in some countries. Thus, a country that has higher enrollment for girls rather than boys in secondary school will score equal to a country where boys’ and girls’ enrollment is the same … ratios obtained above are truncated at the “equality benchmark.”

In other words, this is not actually a measure of equality per se, but rather the extent to which women are equal to men overall on several (but not all) dimensions of life that are important in modern contexts. In most highly developed nations, women are more likely than men to be enrolled in and complete college and have a longer healthy lifespan than men, but these gender gaps disappear in the GGGI. From the 2021 report: “In the case of healthy life expectancy, the equality benchmark is set at 1.06 to capture the fact that women tend to naturally live longer than men. As such, parity is considered to be achieved if, on average, women live five years longer than men.”

There are two points embedded in these two sentences that give us a glimpse at the politics behind the GGGI. The first is that although the GGGI purports to only measure outcomes and not the inputs that create those outcomes, here they are asserting that a biological input results in a female advantage in lifespan and this justifies the 1.06 benchmark. It is true that males have shorter lifespans than females in species with intense male-on-male competition for status and access to mates,2 so the assertion that women naturally live longer than men (assuming a relatively benign environment) is correct. But the reliance on inputs in this instance opens the door to a more thorough examination of the core sources of the overall GGGI gap.

This brings us to the second and most critical point: The same evolutionary and biological processes that, all other things being equal, result in a shorter average lifespan for men than women also contribute to the sex differences in economic outcomes (e.g., annual income) and political participation. It is the gap on these dimensions that drives the overall GGGI gap in highly developed countries and triggers political posturing and handwringing. As noted, a gap in healthy lifespan is common in mammals in which males compete more intensely than females for status and resource control (e.g., territory)—in comparison to females, males of these species generally grow more slowly, are physically larger, behaviorally more aggressive, and have shorter lifespans. The sex differences in economic and political engagement are a modern-day reflection of this more fundamental sex difference in the motivation to achieve status and resource control.3 In every culture in which it has been studied and across historical periods, higher status conferred (and still confers) more reproductive gains to men than to women, and in many contexts influences which men reproduce and which do not, as detailed in an earlier Quillette article. Indeed, one of the factors that contributes to the lifespan gap is the wear and tear of men’s more intense competition (e.g., working long hours) for status and resource control.

There are socio-cultural models that have been proposed to explain the sex differences in focus on status and cultural success,4 but given this evolutionary history and the costs of competing, a biological basis is the most parsimonious explanation. From this perspective, there will never be as many women as men sufficiently motivated to make the trade-offs required to achieve at high levels in economic and political spheres. Hakim’s studies of the number of women with a work-focus (14 percent in her study), home-focus (16 percent), or a balance of the two (70 percent) is consistent with this expectation—only a minority of women are as intensely work-focused as the average man.5

Consequently, sex differences on the economic and political indicators used in the GGGI to measure gender equality should be adjusted to account for these motivational and life-work trade-offs that are part and parcel of the same suite of sex differences that result in a longer lifespan, on average, for women. If sex differences in willingness to make the trade-offs necessary to be culturally successful in the modern world (or anywhere else in the world) were incorporated into the GGGI, the gender equality gap would largely disappear, at least in highly developed nations.

Basic Index of Gender Inequality: BIGI

For the reasons noted above and others, we developed the BIGI as an alternative or at least an adjunct to the GGGI. Our goal was to develop a transparent index that captured the opportunity to lead a long, healthy and satisfying life grounded in educational opportunities.6 We chose relatively straightforward indicators, including primary and secondary educational opportunities, healthy life expectancy, and life satisfaction. Educational opportunities are important because academic competencies at school completion influence economic outcomes in adulthood, as well as one’s ability to cope with the many demands of daily life that are dependent on some level of literacy and numeracy.7 We assumed a universal preference for a long and healthy lifespan.

As noted, the GGGI also includes measures of educational and health outcomes, but unlike the GGGI we don’t truncate the scores if women are doing better than men. In other words, we assume that there could be circumstances in which women are doing better than men, on average, and believe that a gender equality index should reflect any such realities. So, one of the advantages of BIGI is that there are not only countries where women fall (sometimes considerably) behind, but also those in which women appear to do somewhat better. For example, especially in the world’s poorest countries, both boys and even more so girls fall behind in schooling, while in the richest countries, girls do better.

The GGGI does not include a measure of life satisfaction, but we did. This is because it is impossible to measure every aspect of life that might influence one’s wellbeing in one country or another, but overall life satisfaction will reflect the combination of disadvantages and advantages, whatever they might be, that people experience and are important to them.8 So, the shameful and marginalizing treatment of Australian women should result in a substantive gender gap in life satisfaction, favoring Australian men. There is typically a small gap in Australia, but contrary to what we might expect based on GGGI scores, it favors women. It seems that the lower overall participation of Australian women relative to men in the economy and in politics is not undermining their satisfaction in life.

The pattern here is in keeping with many other studies, including a Study of Mathematically Precocious Youth (SMPY), whereby the educational, occupational, and family trajectory of thousands of very talented individuals are followed from adolescence forward. The women and men in this study can succeed in just about any education-dependent field they might choose, and they do. The most relevant finding is that these women and men make different life choices, with more men than women working long hours and focusing on their career—status striving—and more women than men focusing on family and interpersonal relationships.9 Critically, these women and men are equally satisfied with their life; the men are not complaining about the long work hours and the women are not complaining about trading some amount of professional success for time with family and friends.

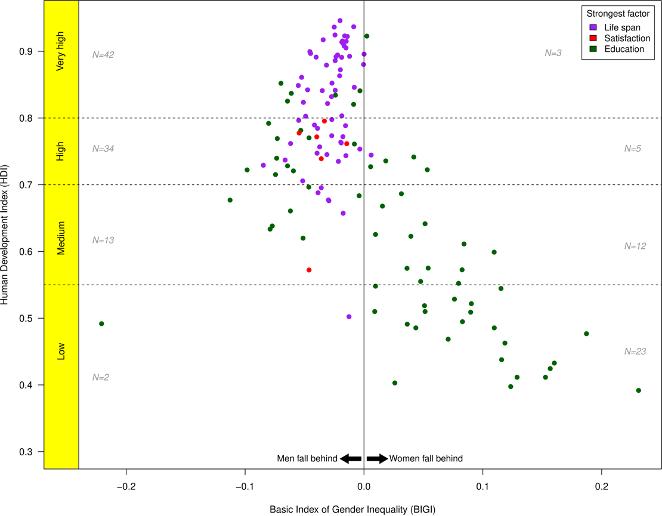

In any case, we combined these measures (i.e., educational opportunity, healthy lifespan, and life satisfaction) to get a sense of how women and men were doing in different parts of the world. Unlike the GGGI where women fall behind at least to some extent in every country in the world, our BIGI measure reveals much more nuance in the wellbeing of men and women, depending on where they live. The figure below shows the overall gender gap on the BIGI, with the largest contributor to this gap color-coded (purple for lifespan, red for life satisfaction, and green for education). The countries were grouped across different levels of social and economic development using the Human Development Index (HDI). Most countries with very high HDI scores are liberal democracies that provide universal education, have a healthy population, and their citizens enjoy a high standard of living. Negative scores on the x-axis indicate that men are falling behind and positive ones that women are falling behind:

As can be seen, there is considerable cross-national variation in whether men or women are relatively disadvantaged. Women fall behind in countries with low levels of economic and social development, largely due to poor educational opportunities. However, as economic and social conditions improve, the relative disadvantage shifts from women to men. There were a handful of countries with a relatively large gap in life satisfaction and they all favored women. In many of these countries, men are completing fewer years of schooling than women—a pattern that continues into college10—and have a shorter lifespan.

Note that if men’s shorter lifespan were strictly due to biology, the gap would be uniform across countries, but this is not the case. There are many highly developed and very highly developed countries in which the gap is larger than we would expect. We showed that some of these gaps were correlated with health-related behaviors, such as alcohol abuse,11 that in turn are more common among men than women and are often exacerbated when men’s avenues for status striving are limited, such as few job opportunities. Job loss is stressful for most people, but on average it compromises men’s mental health more strongly than that of women.12 Unemployed men are also more likely to commit suicide than unemployed women, relative to the rates found for their employed same-sex peers.13 One meta-analytic review (combining results across studies) indicated that the men’s relative risk of suicide increased 51 percent following a prolonged job loss, as compared to 12 percent for women.14 The gap here highlights our earlier point that achievement of status and access to resources is more psychologically prominent among men than women and loss of status and resources more psychologically devastating, lowering life satisfaction.

These types of disadvantages are inconvenient to a certain group of gender activists and thus not captured by the GGGI. Nevertheless, we believe that the GGGI is a useful measure of a country’s level of women’s empowerment, including in dimensions that play a key role in the women’s emancipation movement. We believe that there are in fact countries in which women’s economic and political participation is lower than their preferences and a measure such as the GGGI is thus useful. This, however, does not justify the implicit assumption that these preferences are equal across women and men; to the extent the preferences are unequal, the GGGI overestimates the gap. More to our point, the GGGI ignores or diminishes disadvantages to men, which makes it less useful as a measure of “true” gender equality. To be fair, the GGGI makes no claim to be a measure of “true” equality, but it is nevertheless routinely interpreted as such. While policymakers rightly focus on areas where women’s empowerment might improve (e.g., political representation), the risk is that an over-reliance on a measure such as the GGGI does not consider, or discounts, specific disadvantages of boys and men (especially regarding health and education).

In our view, these types of international measures should reflect the extent to which a country’s policies and practices meet the needs and preferences of their citizens—promoting educational opportunities that foster the ability to live a healthy and satisfying life. Measures such as the GGGI are based on an implicit assumption that women and men have the same preferences in life, but this is a faulty assumption, at least when it comes to the economic and political spheres of life emphasized by the GGGI. One result is that the GGGI will always indicate that women are disadvantaged and thus justify policies to rectify the associated mistreatment of women. The BIGI is not the final word on how to best measure how well one country or the next is fostering the wellbeing of its citizens, but it at least provides us with a more nuanced view, including identifying countries in which women are relatively disadvantaged, those in which men are relatively disadvantaged, and those in which the differences are trivial.

References:

1 Hakim, C. (2002). Lifestyle preferences as determinants of women’s differentiated labor market careers. Work and Occupations, 29, 428–459.

2 Clutton-Brock, T. H., & Isvaran, K. (2007). Sex differences in ageing in natural populations of vertebrates. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences, 274, 3097–3104.

3 Geary, D. C. (2021). Male, female: The evolution of human sex differences (third ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

4 Wood, W., & Eagly, A.H. (2002). A cross-cultural analysis of the behavior of women and men: Implications for the origins of sex differences. Psychological Bulletin, 128, 699–727.

5 Hakim, C. (2002). Lifestyle preferences as determinants of women’s differentiated labor market careers. Work and Occupations, 29, 428–459.

6 Stoet, G. & Geary, D. C. (2019). Basic index of gender inequality: A simplified measure of sex differences in wellbeing. PLoS ONE, 14(1), e0205349.

7 Bynner J. (1997). Basic skills in adolescents’ occupational preparation. Career Development Quarterly, 45, 305–321.

8 Pittau, M. G., Zelli, R., & Gelman, A. (2010). Economic disparities and life satisfaction in European regions. Social Indicators Research, 96, 339–361.

9 Ferriman, K., Lubinski, D., & Benbow, C. P. (2009). Work preferences, life values, and personal views of top math/science graduate students and the profoundly gifted: Developmental changes and gender differences during emerging adulthood and parenthood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97, 517–532.

10 Stoet, G., & Geary, D. C. (2020). Gender differences in the pathways to higher education. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 117, 14073–14076.

11 Wilsnack, R. W., Wilsnack, S. C., Kristjanson, A. F., Vogeltanz‐Holm, N. D., & Gmel, G. (2009). Gender and alcohol consumption: patterns from the multinational GENACIS project. Addiction, 104(9), 1487–1500.

12 Paul, K. I., & Moser, K. (2009). Unemployment impairs mental health: Meta-analyses. Journal of Vocational behavior, 74, 264–282.

13 Milner, A., Page, A., & LaMontagne, A. D. (2014). Cause and effect in studies on unemployment, mental health and suicide: a meta-analytic and conceptual review. Psychological Medicine, 44, 909–917.

14 Milner, A., Page, A., & LaMontagne, A. D. (2014). Cause and effect in studies on unemployment, mental health and suicide: a meta-analytic and conceptual review. Psychological Medicine, 44, 909–917.