Books

Romance and Retribution

As an institution grows and evolves, it inevitably requires reform, but that task can only be entrusted to those who have its best interests at heart.

I.

“This is a crisis of epic proportions,” wrote an alarmed Romance Writers of America (RWA) board member on Christmas Eve as the scenery started to collapse.1 Longstanding tensions within the trade organisation had detonated the previous day when novelist Alyssa Cole revealed that RWA’s board of directors had suspended her friend Courtney Milan. The decision provoked a hurricane of condemnation from the membership, mass resignations from the board, and a spectacularly vicious frenzy of internecine bloodletting online. Milan’s suspension has been widely reported as the latest indignity suffered by a woman of colour in an ongoing battle between RWA’s old guard and minority authors struggling against marginalisation. In this version of events, Milan had exposed and confronted the scourge of racism within RWA and been crucified for it.

For a few days, the forty-year old organisation looked like it might tear itself to pieces, until what remained of the board agreed to commission an independent review of the events that led to Milan’s suspension. RWA retained multinational law firm Pillsbury Winthrop Shaw Pittman LLP to conduct the investigation, and on 18 February 2020, they published its findings. The 58-page report reveals an organisation that had become procedurally inept, confused about its purpose, and internally weakened by political feuding. The first of these criticisms, in particular, was seized upon by Milan and her supporters as proof that she had been the casualty of a terrible injustice. But the report also explicitly rejects Milan’s claim that she had been victimised for campaigning against racism: “The evidence Pillsbury reviewed does not suggest that the adverse finding against Ms. Milan was motivated by animus or bias against her.”2

The controversy had been ignited when, on 8 August, RWA’s President-Elect Carolyn Jewel posted this following tweet (since deleted):

Well. I saw that someone who's been YEARS in the publishing (not writing) business liked a highly problematic tweet and when I checked if that was an accident, their timeline was full of likes of hateful, racist tweets. Sorry, but blocked.

— Carolyn Jewel (@cjewel) August 8, 2019

Jewel did not identify the individual in question, but she informed those who contacted her by direct message that it was Sue Grimshaw.3 The following day, romance novelist Ella Drake publicly identified Grimshaw by posting screenshots of tweets Grimshaw had liked. There was a Trump tweet in which the president thanked the people of El Paso and Dayton; three Charlie Kirk tweets, one of which praised the US Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency; there was a Diamond and Silk tweet which included a video of their appearance on Tucker Carlson’s Fox News show; and there were a few tweets of prayers and Biblical verse from Christian accounts.

In June 2019, Grimshaw had joined romance author Suzan Tisdale’s new indie venture Glenfinnan Publishing. And on 12 August, it emerged that romance author Marie Force had hired Grimshaw as an editor at her Jack’s House Publishing imprint. Both publishers now found themselves besieged by angry tweets and emails demanding to know why they were employing a notorious racist. Grimshaw began deleting her likes and unfollowing accounts in an attempt to escape harassment, before giving up and deleting her account. As far as Drake was concerned, this constituted an admission of guilt. The problem, she explained, was not just Grimshaw’s “white supremacist leanings”; it was that someone with those leanings had previously worked as an acquisition editor at Random House and as a buyer for Borders Group. Grimshaw was one of the gatekeepers in an industry that had long marginalised authors of colour. “If keeping romance white is what Jack’s House is all about,” Drake concluded, “then I guess she’ll fit right in.”

II.

Romance Writers of America was established in 1980 to provide advocacy, networking opportunities, and support to writers of romantic fiction, a genre the organisation’s founders felt was then neglected by the publishing industry. In 1981, RWA held its first annual summer conference, followed the next year by its first awards ceremony. By the time 2019 drew to a close, it had amassed around 9,000 members and established over 100 local chapters nationwide. Its annual awards, known as the RITAs, had become the most prestigious in the genre.

By the 2000s, however, this flourishing community was suffering sporadic outbreaks of squabbling between its reformer and traditionalist tendencies. Reformers, who tended to be younger, wanted romantic fiction to be more socially aware. Parts of the romance canon had dated poorly, they argued, and the representations of blacks, Native Americans, LGBT characters, and other historically marginalised persons were frequently unacceptable by modern standards (when they appeared at all). Romance fiction was “becoming more inclusive,” the founder of the Smart Bitches, Trashy Books website, Sarah Wendell told Glamour, “with more queer protagonists in different subgenres, more characters of color, from different ethnic and cultural backgrounds, and of different religions.”

Risk-averse acquisition editors had often rejected non-traditional stories, believing that their readership wasn’t interested in gay romance or minority couples. The advent of independent publishing revealed this to be poor business sense. Now that authors could bypass publishing houses, new sub-genres brought an explosion of innovative fiction and, with it, new fans to the romance genre. The industry’s reluctance to feature people of colour on the covers of novels by African American authors was also challenged and reappraised, and it is fair to say that some anachronistic assumptions and practices were discarded during this time.

But whenever traditionalist objections interrupted this progressive march, trouble resulted. In 2005, a furious row erupted after RWA’s magazine, the Romance Writers Report, included a poll asking members whether or not the romance genre ought to be defined as between “two people,” or between “a man and a woman.” Traditionalists at RWA were accused of attempting to narrow the genre’s definition in order to exclude LGBT writing and depictions of group sex in explicit fiction known as “romantica.” Then, in 2012, RWA’s Oklahoma Chapter, Romance Writers Ink, decided they would not accept same-sex romance entries in their annual contest. Apparently, there weren’t enough judges who felt comfortable reading, let alone evaluating, that kind of material.

But the most contentious flashpoint became the representation of people of color within RWA itself, particularly among the nominees for its coveted RITA awards. In a long essay for the Guardian entitled “Fifty Shades of White: The Long Fight against Racism in Romance Novels,” Lois Beckett reported: “The romance industry itself has remained overwhelming white, as have the industry’s most prestigious awards ceremony, the Ritas. … And just like the Oscars, the Ritas have become the centre of controversy over unacknowledged racism and bias in the judging process.”

In March 2018, Alyssa Cole’s inter-racial civil war romance An Extraordinary Union was not nominated for that year’s RITAs, even though it had already received multiple awards and been favourably reviewed. “The books that had beat Cole as finalists in the best short historical romance category were all by white women,” wrote Beckett, “all but one set in nineteenth century Britain, featuring white women who fall in love with aristocrats. The heroes were, respectively, one ‘rogue,’ two dukes, two lords, and an earl.” Beckett didn’t venture an opinion on the quality of the finalists. Nor did she say which of the nominated books ought to have been replaced by Cole’s or on what grounds.

Under-representation of writers of colour among RWA’s membership (80 percent of which is white) and RITA finalists created the perception that the organisation had a problem, and this perception rapidly became an accepted fact from which all further conversation was expected to follow. Nor was this simply a diversity problem, some of the more radical reformers began to insist—it was a structural racism problem; a white supremacy problem; and the only debate worth having was about how the battle against this menace ought to be prosecuted. When romance author Suzanne Brockmann collected her lifetime achievement award at the 2018 RITA awards, she had this to say to her hosts and anyone else who urged patience, civility, and forbearance in pursuit of social justice:

RWA, I’ve been watching you grapple as you attempt to deal with the homophobic, racist white supremacy on which our nation and the publishing industry is based. It’s long past time for that to change. But hear me, writers, when I say: it doesn’t happen if we’re too fucking nice.

Brockmann went on to call the 53 percent of white American women who had voted for Donald Trump racists and challenged them to prove her wrong by voting the “hateful racist traitors” out of office. It was an inflammatory and divisive address marinated in bromides of love and tolerance, and it was rewarded with whoops, cheers, and a standing ovation. As 2018 drew to a close, sides were being chosen within RWA. Are you with us or are you with white supremacy?

For a white-supremacist organisation, RWA responded to Brockmann’s indictment with remarkable contrition. Following the RITAs, it released an unsigned statement acknowledging that “less than half of one percent of the total number of finalist books” between 2000 and 2017 were by black authors and that “no black romance author has ever won a RITA.” “It is impossible to deny,” the statement continued, “that this is a serious issue and that it needs to be addressed. RWA Board is committed to serving all of its members. Educating everyone about these statistics is the first step in trying to fix this problem.”

But when the slate of 2019 RITA finalists proved to be no more diverse than the 2018 cohort, the news was met with renewed resentment. “The list,” tweeted romance author Bree Bridges, “is painfully, painfully white. And straight. And Christian. And cis. And just basically it is what it is.” Nor did it pass unnoticed that Alyssa Cole’s latest novel had been overlooked again. And so the board released yet another remorseful statement, in which President HelenKay Dimon promised various reforms to the selection process, judging and scoring, and anything else that might help to satisfy growing activist demands.

It was too late. An influential and growing component of the membership was by now disenchanted with such promises, and their rhetoric was becoming more strident. Whether or not Dimon’s interventions would have produced the desired results is moot. The race row that was about to consume RWA would lead to the cancellation of the following year’s RITA awards for the first time in the organisation’s forty-year history, and almost finish off the organisation itself.

III.

One of the most militant and powerful voices in RWA’s reform movement belonged to a bestselling writer and former board member by the pen-name of Courtney Milan. Born Heidi Bond in 1976 to a Chinese mother and American father, Milan began writing in 2009 while she was teaching at Seattle’s School of Law, and her first novel Proof by Seduction was published by Harlequin just a year later. Milan was so prolific and popular that only 18 months after she began self-publishing in 2011, she was able to quit her job to write full time. In 2014, she was elected to RWA’s board of directors, and there she pursued diversity activism with a zeal that electrified her supporters and cowed her opponents. Both agreed that during the four years she served on the board—for good or ill, respectively—Milan played a central role in reshaping RWA policy.

In 2017, former RWA board member Linda Howard posted in a private RWA forum to register her unhappiness with the organisation’s new direction. “I just want to clear up a misconception,” she began:

RWA isn’t a democracy, it’s an organization, and that’s a big difference. The board of directors aren’t elected to represent the membership, they are elected to run the organization to make it as strong and efficient as possible, because a strong organization can best represent the interests of its members to the publishing world… Unfortunately, the last four boards have, with the best of intentions, drastically weakened RWA.

RWA was haemorrhaging members, she warned, “because an organization more focused on social issues than publishing ones doesn’t meet their career needs.” Howard didn’t mention Milan by name, but it was to the influence of Milan’s agenda that she was plainly objecting. In a subsequent post, Howard was even more direct:

I’ve seen a drastic reduction in my local chapter. Members have just walked away, not because of where they are in their careers but because of the way some sensitive issues were handled. Diversity for the sake of diversity is discrimination. It just is. Discrimination against any group shouldn’t be tolerated, it has no place in RWA, and there were already procedures in place to deal with it… Just make the rules clear, fair, and the playing field level. That’s it.

Needless to say, when these remarks (reproduced here, along with some deeply unsympathetic commentary) were leaked onto Twitter, they did not go down well at all. So brutal was the blowback that Howard left the organisation of which she had been a member since the year it was established. “We collectively kicked her ass,” Milan would later crow.

So, by the time she joined the attacks on Sue Grimshaw in the summer of 2019, Courtney Milan had already established a reputation as a formidable personality and a ruthless activist able to command the attention of a ferociously loyal following. Just a few weeks previously, her moral authority within RWA had been reaffirmed with a Service Award, given in recognition of her contributions to diversity and inclusion. Her intervention on 16 August, then, represented an escalation of hostilities: “Sue Grimshaw was the romance buyer for Borders, one of the biggest buyers for romance,” Milan wrote. “She was capable of making a romance novelists’ career by putting their work front and center around the country… And the corollary to being able to make someone’s career with favorable placement? Is the ability to break it by not buying the book at all. We don’t know. We don’t KNOW. But for decades, Black romance authors heard there was no market for their work.”

In fact, we do know. At Borders, all fiction by black authors—including romance—was handled by a dedicated buyer. Grimshaw was the romance buyer so she was given no say in which black authors were or were not purchased. And no good evidence was ever produced, even by her most vehement critics, that Grimshaw had ever impeded the career of anyone, irrespective of their race or sexuality. But now that her Twitter history had been exposed, any aspersion or innuendo, no matter how thinly evidenced, could be tossed onto the charge sheet. Under the misapprehension that Grimshaw was an RWA member, Milan speculated that she might be in violation of the organisation’s non-discrimination clause. So, she solicited information from writers of color to help build a case. The next day, Marie Force announced that Grimshaw and Jack’s House Publishing had “agreed to part company.”

Attention now turned to Suzan Tisdale’s new start-up Glenfinnan Publishing for which Grimshaw also worked as acquisition editor. Pressed by Milan and others to denounce and sack her colleague, Tisdale broadcast a twelve-minute video defending her instead. She made a plea for greater tolerance, warned that negative partisanship was tearing the country apart, and affirmed that she didn’t care about the race or sexual orientation of an author provided they could write a good story. Instead of calling for Sue Grimshaw’s “head on a frickin’ platter,” she suggested, her critics ought to “try to get to know her better”:

Sue is no more a racist or a bigot than I am. She is a conservative woman, but not the kind of conservative woman you might be conjuring up images of. Last I checked, this was still America, and we are all allowed our political opinions. Sue is a Christian, and she has conservative leanings, but that does not mean she is a skinhead or a member of the KKK or an antisemite or anything like that.

Milan was apoplectic, and responded with a new tweet thread, in which she moved with such rapidity and venom from suspicion to accusation to conviction, that it takes a moment to realise not a shred of evidence has been produced in support of anything:

Uhhh why is @SuzanTisdale gaslighting us? … Nobody is saying [Grimshaw]’s a skinhead or a member of the KKK. They’re saying that she was a gatekeeper who may have kept marginalized people out of stores and publishing deals. And if your video says that Sue is no more a racist than you, you sound EXTREMELY racist. Nobody wants anyone to hate anyone, but like if someone used institutional power to discriminate on the basis of race, I don’t think they should continue to have institutional power. And if your institution insists on giving that person institutional power, I hope your institution fails.

And like, if your line of acceptability is “calling for the annihilation of a group of people” but you don’t have an issue with systemically excluding a race of people from bookstores and publishing contracts? Then you are DEFINITELY a racist. And like, @SuzanTisdale is entitled to be a racist and to run her publishing house as a racist, but you know, we’re entitled to just not read or review her books because I hate racist books.

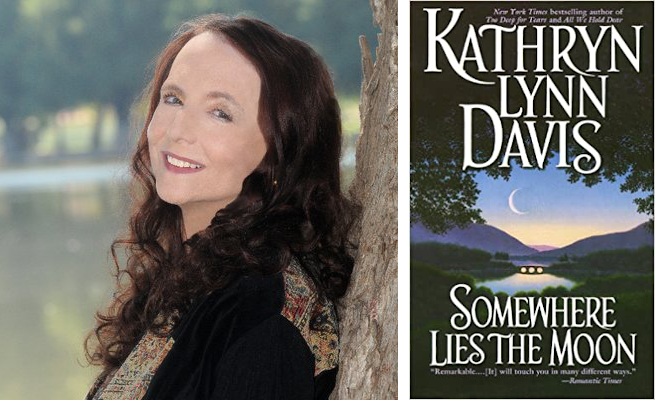

The following evening, one of Milan’s Twitter followers, Lisa Lin, sent her a message linking her to the Amazon preview of a novel entitled Somewhere Lies the Moon. It was, Lin pointed out, written by “Kathryn Lynn Davis, Suzan Tisdale’s other editor at Glenfinnan.”4 Neither Milan nor Lin had actually read the book, but Milan returned to Twitter armed with information gleaned from the previewed excerpts and denounced it as “a fucking racist mess.” For another eighteen tweets, she emptied ridicule and scorn over Davis and her work, even though she admitted she hadn’t even bothered to read all of the free sample (“I don’t need to”). She was particularly bothered by Davis’s portrayal of the half-Chinese heroine with blue eyes: “As a half-Chinese person with brown eyes, seriously fuck this piece of shit. Thanks.”

The following day, August 26th, Sue Grimshaw emailed Carol Ritter, RWA’s Deputy Executive Director, asking for advice. A group of authors were targeting her on Twitter, she said, and the controversy had already cost her one job. Now she was worried she might lose her position at Glenfinnan too. “The comments they are making are so far from the truth it’s defaming, and now they are even becoming more vile… The author spearheading the hate toward myself and Suzan’s company is Courtney Milan, along with a handful of her followers… Please share your thoughts and suggestions, I’m not sure what I can do at this point…”5

Because Grimshaw was not an RWA member, there was nothing Ritter could do from an administrative standpoint, but she said she would forward Grimshaw’s message to RWA’s corporate counsel. The following afternoon, Suzan Tisdale and Kathryn Lynn Davis also called the RWA office in search of help and advice. Both were told that, as RWA members, they were entitled to file an ethics complaint if they thought RWA’s code of ethics had been breached. The executive director would review the complaints and pass them to the ethics committee if she decided they merited further investigation.6 Both Tisdale and Davis said they would do so.

This ought to have been the start of a routine bureaucratic procedure. But the crisis bearing down on RWA was not one the organisation was equipped to handle.

IV.

The only person at RWA who seemed to grasp the danger the row posed to the organisation was its executive director, Allison Kelley. Kelley had overseen the administration of RWA since 1995 and was due to retire at the end of the year. But the ethics procedures were in a muddle, and the situation was making her nervous. The last time the code of ethics had been redrafted on the advice of corporate counsel was in 2003. Since then, multiple amendments—many of them proposed by HelenKay Dimon after she and Courtney Milan joined the board in 2014—had left its provisions confused and incoherent.

On June 14th, Kelley wrote to Dimon, who was by now RWA board president, and President-Elect Carolyn Jewel, who would take over on 1 September. “Complaints [between the members] are increasing,” she warned, “and usually allege discrimination based on racism… In my opinion, we are on thin ice in many situations, and we need to tread carefully until all policies and related discipline are consistently written and applied.”7 In July, the board met and voted—again without consulting counsel—to incorporate RWA’s anti-discrimination policy into the code of ethics and amend a provision that arbitrarily exempted member behaviour on social media. On Friday, August 16th, Dimon was still fretting about whether to remove the social media exemption entirely when Courtney Milan fired her opening salvo at Sue Grimshaw.8

The following Monday, Allison Kelley emailed senior board members to report that Milan was attacking Grimshaw on Twitter and that Grimshaw had just lost her job with Jack’s House Publishing as a result. Milan, she added, was encouraging RWA members to file ethics complaints against Grimshaw for violating the recently adopted anti-discrimination provision. Neither Carolyn Jewel (who would become president on 1 September) nor Damon Suede (who would take her place as president-elect the same day) were sympathetic. Jewel admitted that it was her tweet that had first brought attention to Grimshaw’s Twitter history, and that she had passed Grimshaw’s name to anyone who asked for it by direct message. She said she thought Milan “had pointed out the truth.” Suede agreed, adding that if anyone deserved censure and stigmatisation it was Grimshaw.9

But Kelley was still uneasy, and worried about the antitrust implications of punishing members for political views. “My concern is the implication that RWA can or should do something to Sue,” she wrote. “…some members are now expecting RWA to take immediate action to discipline members and industry professionals without proof or due process. I don’t think it should be RWA’s job to do extensive research in order to determine motive, nor should RWA assume motive.”10 After Milan published her furious response to Suzan Tisdale’s video and then tore into Kathryn Lynn Davis and her novel, even HelenKay Dimon reluctantly acknowledged the problem. Allison Kelley had by now read Grimshaw’s email asking for advice and had spoken to Tisdale and Davis. “FYI,” she told her colleagues, “the complaints continue and authors are alleging defamation and injury to their careers.”11

But when Tisdale filed her ethics complaint against Milan later that day, the board was faced with a new dilemma: The previous year, they had appointed Courtney Milan chair of the ethics committee. The ludicrous decision to give this job to one of the organisation’s most belligerent troublemakers had been Dimon’s idea, and even Milan was uncertain that it was a smart move. “I am worried that because Courtney is Mean, someone will file an ethics complaint against me,” she wrote when Dimon offered her the post, “and that will complicate things for a bit.” Dimon’s response to this rather prescient objection was deferential:

Allison [Kelley] and I were talking today and [I] told her I asked you. She was greatly relieved and very excited. In my view, and Allison agrees with me, you profoundly changed the direction of RWA for the better by being on the Board. The general membership might not get how instrumental you were in making us look at RWA in a different way—seeing our weaknesses, realizing we were leaving people behind and taking responsibility for our mistakes—but Allison and I know.12

By the time Suzan Tisdale’s ethics complaint landed on her desk, Kelley’s relief and excitement had evidently waned. Milan’s zealotry had become an administrative headache, and now it was in danger of becoming a legal headache, too. She and her deputy Carol Ritter spoke to corporate counsel, who explained that RWA might be at risk because, as ethics committee chair, “Courtney has an official capacity at RWA.” In a subsequent email, the lawyer added, “I don’t think you are going to have any choice but to proceed with the ethics complaint.”13

Dimon was not about to rethink her assessment of Milan, but it was now clear that Milan would have to be persuaded to resign her position as ethics committee chair. On August 29th, Milan was notified that a complaint had been filed against her and she immediately agreed to step down. Two days later, having evidently reconsidered her response, she emailed HelenKay Dimon and Carolyn Jewel. It was Dimon’s last day as president:

I hereby officially disagree with [Tisdale’s] claims for the record. I don’t want to unresign—my policy has always been that if you want my service, you have it, and if you don’t, I will spare myself the workload—but I will remind HelenKay that I explicitly told her this could be an issue when she asked me to serve.

For Carolyn: Now that I have had a chance to review this complaint and think about it in depth, we are going to have to talk at some point about the fact that staff did not follow their usual procedure for Ethics complaints in this case—a thing that I am personally aware of, since I have had discussions with Allison about usual procedure, which I suspect very few other people have.

I can only guess at the reasons, and while I’m sure that the thinking was that this was in the institution’s best interest and not anything personal to me, I am also not okay with the fact that I have not been given the same procedure as others.14

If Milan’s complaint was handled differently, it was probably because the board had actually sought legal advice for a change, and because Allison Kelley was finally out of patience. The previous day she had emailed Dimon asking permission to recuse herself from further involvement. “After defending Courtney’s right to free speech to members for at least four years,” Kelley wrote, “I have reached my limit. I honestly and sincerely appreciate that Courtney opened my eyes to problems I was blind to, but I simply cannot defend her tactics.”15

V.

On her first day as president, Carolyn Jewel, whose tweet about Grimshaw had been the proximate cause of the row in which her organisation was now entangled, resolved to appoint an entirely separate ethics committee to handle the Tisdale and Davis complaints. This decision was later portrayed by Milan’s supporters as sinister, but Jewel’s reasoning was prudent under the circumstances. She worried that if the remaining committee members were asked to consider a complaint against their former chair, it risked the perception of a conflict of interest that might be used to discredit the process after the fact. The existence of the new panel was not revealed to the rest of the board or members of the existing committee.16

The newly impaneled ethics committee finally convened to consider Suzan Tisdale’s and Kathryn Lynn Davis’s complaints via conference call on November 19th. Carolyn Jewel had recused herself, due to her involvement at the beginning of the controversy, so President-Elect Damon Suede, who until now had been unaware that a complaint was pending against Milan, became the board’s liaison. Carol Ritter acted as staff liaison. Everyone involved signed confidentiality and conflict of interest agreements.

Before them, the committee had the formal complaints from Suzan Tisdale and Kathryn Lynn Davis, Courtney Milan’s two responses, and supporting dossiers of screenshots submitted by Tisdale and Milan. No other information was provided and none was requested by the committee. However, it soon became apparent that nobody really knew what they were doing. The committee members had no experience of, or training in, handling complaints. They had to ask Carol Ritter for a template report so they knew what kind of document they were expected to produce. And they were nonplussed by some of the language in RWA’s various policy documents. The new provisions of the code of ethics incorporated early that summer prohibited “invidious discrimination”—but what did that mean? An idiosyncratic working definition was cobbled together after a Google search.17

The first half of Tisdale’s complaint rehearsed the story of Milan’s attacks on her publishing company and colleagues, which she described as “nothing short of libelous vitriol.” She added that three authors had left Glenfinnan as a result of the controversy, and that Davis had lost a lucrative three-book contract with another publisher (she later clarified that the contract had not been signed but that negotiations had been derailed). The second half of Tisdale’s complaint was a cri de coeur, beseeching the board to do something about Milan’s behaviour:

Ms. Milan has a history of similar vicious, false, and uncalled for confrontations. For reasons I cannot begin to comprehend, the RWA has ignored this unethical behavior for far too long. Is this truly what the RWA wants? Is your silence on these matters the board’s way of saying you agree with Ms. Milan?18

Tisdale threatened RWA with legal action if they did not take steps to end Milan’s attacks. “I will accept nothing less,” she wrote, “than a full, public apology from Ms. Milan not only to myself, but to Ms. Grimshaw and Ms. Davis, as well as all the Glenfinnan authors.”19

The Kathryn Lynn Davis complaint was longer because it included a defence of her book, which she said Milan had selectively quoted, misunderstood, and maliciously misrepresented. Her exasperation was palpable. “[Ms. Milan] speaks without authority, without thought, without actually reading, her only goal is to tear down those with whom she does not agree”20:

From her behavior on Twitter, she seems to believe diversity belongs only to her, to defend in the most divisive, vicious, and unprofessional way possible. Rather than fostering an environment of creative and professional growth, she inspires fear in her audience, who know how many writers she has already destroyed. She quashes creativity and growth through the use of terror tactics. She seems determined to stop the free exchange of ideas, knowledge, and diverse career experiences by aggressively and violently (through word choice) assaulting those who disagree with her. Or even those, like me, who have never had any interaction with her at all.21

To all this, Milan responded with haughty disdain. The Tisdale complaint, she wrote, “is simple to resolve for three reasons”:

First, none of the conduct that Tisdale complains of is a violation of RWA’s Code of Ethics. Second, Tisdale’s complaint contains numerous assertions which are not supported by any evidence, refer to the speech of people other than myself, or are contradicted by her own screenshots. Finally, the primary conduct that Tisdale wants RWA to punish is that I, a half Chinese-American woman, spoke out against negative stereotypes of half Chinese-American women. Far from being dishonest or disingenuous, my expression here is that of deeply-held beliefs which I have discussed for years.22

Milan then proceeded through a detailed retelling of events from her perspective, followed by a scornful quasi-legal analysis of the ethics provisions she was accused of violating. Since personal social media accounts were not covered by RWA’s code of ethics, she pointed out, her behaviour lay beyond the committee’s jurisdiction. She concluded on a piteous note:

I am emotional about these issues. Negative stereotypes of Chinese women have impacted my life, the life of my mother, my sisters, and my friends. They fuel violence and abuse against women like me. And they dishonor the memory of the strong women who I am descended from on my mother’s side of the family. I have strong feeling about these stereotypes, and when I speak about them, I use strong language. It is hard not to be upset about something that has done me and my loved ones real harm.23

There would be, she vowed, no apology. In her response to Davis, she added:

Even if I was entirely mistaken about everything I said about her book, RWA’s Code of Ethics is very clearly meant to exclude honest discussions of books. Davis is mad about a negative book review. She has a right to be mad, but she does not have a right to drag RWA and the Ethics Committee into her anger.24

Between them, Tisdale and Davis had alleged seven violations of the RWA code of ethics, and on five counts the committee found that no violation of the code had occurred. But this was partly because Milan’s conduct was protected by the clause exempting private social media accounts. She had, the committee members pointedly noted, “served on the Board when this exception was approved, and very likely understood she would be able to act in the manner she did, without being in violation of the code.” To their evident frustration, this precluded them from finding Milan guilty of “intimidating conduct that objectively threaten a member’s career, reputation, safety or wellbeing.”

Actually, this seems to have been the entire point of the exemption, which makes no sense otherwise. A code of ethics is intended to govern member conduct, so why provide for a public forum in which conduct expressly forbidden by the code could be engaged in with impunity? As one of the committee members pointed out at a preliminary meeting:

It seems to me that considering the board did exclude social media—for whatever reason—in doing so they pretty much gutted that provision of the ethics policy that has to do with harming another member’s business, career, etc. I’m not sure why we even have that clause now.25

However, the committee did find for Tisdale and Davis on one count each, and their verdict was unanimous. Milan’s attacks on Glenfinnan, the committee decided, had violated the recently included provision prohibiting “invidious discrimination,” and therefore a second clause in the code that forbids members from “repeatedly or intentionally engaging in conduct injurious to RWA or its purposes.” Milan’s actions, despite her protestations, reflected poorly on the RWA. The committee recommended that Milan be censured, suspended from RWA for a year, and banned from holding a leadership position in the RWA or any of its chapters. They added this recommendation, which makes clear their attitude to Milan’s behaviour and the rules that protected her:

Inasmuch as the committee felt its hands were tied in the matter of adjudicating postings on social media not operated by RWA, no matter how egregious the author’s intent, the committee recommends that the RWA Board revisit this matter in light of the circumstances of this complaint.26

The ethics committee completed its report on 11 December and sent it to RWA President Jewel. It now had to be ratified. On 7 December, a board meeting was convened. At which point, the already groaning architecture of the RWA ethics procedure collapsed.

VI.

The terse five-page document the ethics committee submitted, following the template provided by Carol Ritter, was hopelessly inadequate. It mentioned only that Tisdale and Davis had been accused of racism by Milan and that Milan felt that her accusations were justified and that her behaviour was, in any case, permissible under the code. There was no discussion of the background to the case, the personalities involved, or the specifics of the claims and counter-claims at issue. Nor was there any clear explanation of the committee’s reasoning—the report cites the code of ethics and the policy manual but doesn’t explain how the two documents or their relevant provisions relate to one another, or precisely how they had been violated. Board members were not provided with copies of the complaints, Milan’s responses, or any of the supporting documentation.

President-Elect Damon Suede, who as board liaison had sat in on the committee’s deliberations, suddenly found himself fielding a battery of questions. What was Milan supposed to have done, exactly? And why was she being punished for behavior on social media when that was explicitly excluded by a provision in the code? Was there additional evidence of misconduct outside of social media? Was the board expected to simply wave through whatever the committee recommended? Board members had every reason to be anxious. Membership of the ethics committee was confidential, but membership of the board was not. Once the board approved the committee’s report, they would be taking ownership of its findings and might be called upon to defend them. How were they expected to do that if they weren’t permitted to assess the grievances at issue and had no idea how or why the committee had arrived at its conclusions?

When Sue Grimshaw was first attacked by Courtney Milan on Twitter, Suede had shrugged. But over the intervening months, his view had changed. Now he tried to assuage board members’ misgivings and encouraged them to approve the committee’s findings. The problem was he incorrectly assumed that the terms of the confidentiality agreement he had signed prevented him from disclosing anything at all about its deliberations. So instead he spoke in general terms of the fastidious care with which the committee had considered the complaints, the “egregious” nature of Milan’s behaviour, and the “reams and reams” of supporting evidence which unfortunately he could not disclose, including information not already publicly available (there were, it would turn out, two DM exchanges). Pressed to explain what was so terrible about Milan’s behaviour, Suede compared her to a boss who repeatedly exposes himself to his staff—a fantastically unhelpful analogy.

Members of the board felt browbeaten and said so. Perhaps aware he had gone too far, Suede told them to vote according to conscience and reminded them that they could reject the report outright or request revisions. The report was approved by 10 votes to five with one abstention. The board declined to censure Milan, but voted to impose the one-year suspension and the lifetime ban on holding office in RWA. A number of board members remained unhappy about being asked to ratify a decision without the necessary background material and urged a change in procedures so this situation was not repeated.27

The whole ugly episode seemed to be coming to an end. All that remained was for Carol Ritter to notify Milan, Tisdale, and Davis. She did not know that on August 30th, the day after Suzan Tisdale filed her ethics complaint, Allison Kelley had told Milan that neither complainants nor accused were bound by confidentiality. So, on December 23rd, when Carol Ritter sent the three women copies of the ethics report, Milan passed it to her friend Alyssa Cole who immediately published it on Twitter, along with the two complaints and Milan’s responses:

One of the reasons I believed in RWA was because I saw how hard my friend, Courtney Milan, worked to push the organization’s inclusiveness. Today, the day before Christmas Eve, RWA notified her they’d agreed with ethics complaints filed against her for calling out racism.

— Alyssa “mostly updates” Cole (@AlyssaColeLit) December 24, 2019

Cole’s tweet was shared over 1,600 times and received over 4,400 likes. At a stroke, it concretised a version of events in which Courtney Milan had been martyred by an institutionally racist organisation. “If anyone wants to know why I’m posting this, and not her,” Cole went on: “I’ve seen Courtney speak out on other people’s behalf for years, without a second thought. There’s no reason she should have to take this on by herself. Also: I’m furious.”

Tisdale and Davis had submitted complaints on the understanding that they would be handled discreetly. Now those documents were splashed across social media and they were being vilified all over again. On Christmas Eve 2019, romance author Kathryn Lynn Davis posted a message on her Facebook page that read: “I wish all of my friends, followers and readers the Happiest of Holidays and a New Year filled with joy and promise.” To which someone spat back: “Fuck you, you racist Nazi bitch.”

The board watched aghast. RWA members were going berserk and board members’ Twitter mentions and email inboxes had become volcanoes of enraged invective. How on Earth did the public suddenly have access to material the board had been prevented from reviewing? A number of members accused Suede of misleading them, and improperly withholding evidence they needed to reach an informed judgement. At an emergency board meeting the next day, Suede attempted to defend the process, but it was a dead loss. A motion was hastily passed to rescind approval of Milan’s punishment “pending an opinion from RWA’s attorney,”28 but two tweets announcing the decision only inflamed the situation:

RWA reiterates its support for diversity, inclusivity and equity and its commitment to provide an open environment for all members. 2/2

— RWA (@romancewriters) December 25, 2019

Over the Christmas period, each passing day was worse than the last for RWA. One of Milan’s supporters, Claire Ryan, began to assemble a timeline of events as the crisis unfolded, which she updated as new information became available. The lengthy entries between Christmas Eve and the middle of January are just a rolling cascade of terrible news. RITA judges and committee members began an exodus; new allegations of bigotry and discrimination within RWA were posted and circulated; an unrelated controversy involving Damon Suede and DreamSpinner Press was revived; authors and agents announced their intention to boycott RWA events and return their RITA award statues.

On December 26th, eight board members resigned and Carolyn Jewel stepped down as president. Ryan reported that the “hashtags #IStandWithCourtney and #IStandWithCourtneyMilan reach[ed] 23.7k tweets and 12.7k tweets respectively on Twitter.” As the new president and board liaison who had overseen the deliberations of the ethics committee, Damon Suede now became the focus of members’ incontinent rage as he tried to hold the disintegrating organisation together. An RWA member posted an excerpt of one of Suede’s novels on Twitter and accused him of racism. Allegations were made by numerous parties that he had falsified the number of books he had published to meet the eligibility requirement for president. A petition to force a recall election was circulated and delivered to RWA on New Year’s Eve, signed by 1,092 members.

Meanwhile, publishers, partners, and sponsors announced their intention to boycott the RWA’s annual conference, and were rewarded with thousands of likes and retweets for doing so. As confidence in RWA plummeted, everyone scrambled to disassociate themselves from the embattled organisation. It was like watching a run on a bank. The legacy press was by now running stories on the crisis, almost all of which framed the story to Milan’s advantage, implicitly—and sometimes explicitly—endorsing her claim to having been forced out of a racist organisation. Milan and her supporters demanded an audit of the whole affair, and when that was duly commissioned, they demanded that the board of directors make the findings public. They were now dictating events, and they gloated as RWA reeled under their attacks.

On January 6th, RWA announced that it would be cancelling the 2020 RITAs and refunding entry fees. Three days later, Damon Suede resigned. He’d only been in the job two weeks and it had become intolerable. Carol Ritter, who had briefly followed Allison Kelley as executive director, quit the same day. On January 12th, six days before publication of the Pillsbury audit, all remaining members of the board stepped down. Staff were busy processing member resignations. RWA was hanging by a thread.

VII.

On 3 February, Milan gave an interview to Sarah Weddell’s Smart Bitches, Trashy Books podcast. Invited by her ceaselessly ingratiating host to close out the discussion in her own words, Milan delivered a familiar rebuke to those she accused of “tone policing” women of colour:

It is not our job to make you comfortable, and it is, in fact, white supremacy that makes you think it is our job to make you comfortable. The truth of the matter is we’re in an uncomfortable situation, and your racism makes us uncomfortable, and when we make you uncomfortable by pointing it out, all we’re doing is redistributing the load to where it belongs. So, stop telling people that you have to make people comfortable in order for them to address their racism. That is, in fact, itself an act of racism that reinforces white supremacy.

In other words: If you find my accusations of racism offensive, that’s just confirmation of your racism. In 2010, the blogger Eric S. Raymond described this mode of argument as “so fallacious and manipulative that those subjected to it are entitled to reject it based entirely on the form of the argument, without reference to whatever particular sin or thoughtcrime is being alleged.” He called it “kafkatrapping” because, like the protagonist of Franz Kafka’s novel The Trial, the accused is offered no avenue of exoneration:

Real crimes—actual transgressions against flesh-and-blood individuals—are generally not specified. The aim of the kafkatrap is to produce a kind of free-floating guilt in the subject, a conviction of sinfulness that can be manipulated by the operator to make the subject say and do things that are convenient to the operator’s personal, political, or religious goals. Ideally, the subject will then internalize these demands, and then become complicit in the kafkatrapping of others.

Milan and her allies applied this technique with such pitiless efficiency that RWA was left unable to enforce the most basic standards of member conduct. The various provisions of the ethics code may have been a mess, and the committee may have misunderstood the legal meaning of “invidious discrimination,” but the code’s intention is made perfectly clear in its opening lines: “The RWA Member Code of Ethics… is designed to cause RWA members to exhibit integrity, honesty, and other good professional practices, thereby enhancing the romance writing profession.” Milan’s campaign against Glenfinnan Publishing exhibited none of these qualities, but in the fight against white supremacy, she felt entitled to use any means necessary.

RWA had welcomed Milan into its club; its members had voted her onto the board twice and appointed her chair of the ethics committee; its judges had nominated her for three RITAs and awarded her one; its board had embraced many of her diversity initiatives and recognised her dedication with an official service award; Carolyn Jewel and Damon Suede had even cravenly endorsed her unprovoked attacks on Sue Grimshaw. And yet, Milan and her supporters managed to convince almost everyone of the preposterous idea that she had been punished for speaking out about racism. “The kafkatrapper’s objective is to hook into chronic self-doubt in the subject and inflate it,” Raymond explained, “in much the same way an emotional abuser convinces a victim that the abuse is deserved—in fact, the mechanism is identical.”

Milan claimed she had been denied due process, but practiced reputational terrorism based on nothing but hearsay and uninformed conjecture. She accused Allison Kelley and Carol Ritter of suppressing complaints about racism, but as Kelley explained to the auditor, “most members have declined to file formal complaints after learning that the subject of the ethics complaint would be informed of who had filed it.”29 Milan even accused Ritter and Kelley of obstructing her diversity demands with spurious legal objections, apparently unaware that trying to get someone expelled for their politics was a violation of the organisation’s bylaws. “What we’re dealing with,” Milan told Wendell, “is white supremacy.”

The board was working in a poisonous environment that it had helped to create, and its members certainly made their share of mistakes. But no-one behaved with the fanatical malice of Milan and her supporters. Sue Grimshaw had no quarrel with anyone. She wasn’t even an RWA member, and she was attacked for being a conservative Republican and a Christian. Suzan Tisdale was attacked for refusing to sack Grimshaw. Kathryn Lynn Davis was attacked simply because she happened to work for Tisdale—the idea that Milan’s spiteful attack on Davis’s novel constituted “honest discussion” of a book she hadn’t even bothered to read is absurd. And when Tisdale refused to surrender her colleagues to the mob, its retribution exacted a steep reputational price.

Protected from the effects of the kafkatrap by their anonymity, the ethics committee decided that, no, this was not okay. It is worth repeating that they reached this conclusion unanimously. The chair later told the authors of the audit that they would probably not have found Milan in breach of the ethics code, had she expressed her misgivings about Tisdale and Davis in a more temperate manner: “I think that probably would have cast it very differently, the language itself was so incendiary, it was so problematic, so horrible. It was considered a very horrific thing to go after another member of RWA’s publishing house, and the reputation of RWA would suffer probably as much as anything else.”30

The idea that Courtney Milan’s behaviour was permitted by the code of ethics does violence to even the most basic sense of fairness. But an organisation founded to advance the shared interests of romance authors had allowed itself to be convinced that its diversity record was the true measure of its legitimacy. RWA founding member Linda Howard had been right when she argued in 2017 that RWA was losing sight of its purpose. That she was drummed out for saying so was an early, unheeded warning of just how confused the organization had become.

But RWA’s most serious mistake was to empower those within its ranks who most bitterly despised it—members like Courtney Milan and Suzanne Brockmann, who saw the organisation as just another fortress of homophobic white supremacy to be conquered or destroyed. As institutions grow and evolve, they inevitably require reform, but that task can only be entrusted to those who love the institution—because only they will have its best interests at heart.

UPDATE 3 April: The interim board elected on March 23 to complete the 2019–2020 term released a statement yesterday announcing that they had “voted by unanimous consent to expunge both of the ethics complaints against Courtney Milan, and their ensuing proceedings, from the record.” They offered Milan “a heartfelt apology for how the proceedings were handled and for the impact of this terrible situation on her.”

UPDATE 30 May 2024: Publishers Weekly reports that the RWA has filed for chapter 11 bankruptcy, due to the organisation’s inability “to cover the hotel costs for its annual conferences due to dwindling membership.”

References:

1 INDEPENDENT ETHICS AUDIT REPORT for Romance Writers of America, by Julia E. Judish Jerald A. Jacobs for Pillsbury Winthrop Shaw Pittman LLP. February 19th, 2020, p. 41

2 Ibid. p. 1

3 Ibid. p. 16

4 Courtney Milan Supporting Documents, Exhibit N, submitted September 4th, 2019

5 INDEPENDENT ETHICS AUDIT REPORT for Romance Writers of America, by Julia E. Judish Jerald A. Jacobs for Pillsbury Winthrop Shaw Pittman LLP. February 19th, 2020. p. 19

6 Ibid., p. 20

7 Ibid., p. 7

8 Ibid., pp. 14–15

9 Ibid., pp. 15–18

10 Ibid., pp. 17–18

11 Ibid., pp. 20–21

12 Ibid., pp. 13–14

13 Ibid., p. 21

14 Ibid., p. 23

15 Ibid., pp. 22–23

16 Ibid., p. 24–25

17 Ibid., p. 31

18 Suzan Tisdale Formal RWA complaint, submitted August 27th, 2019, p. 5

19 Ibid., p. 6

20 Kathryn Lynn Davis Formal RWA Complaint, submitted September 11th, 2019, p. 10

21 Ibid., pp. 2–3

22 Courtney Milan Formal Response to Suzan Tisdale Complaint, submitted September 4th, 2019, p. 1

23 Ibid., p. 7

24 Courtney Milan Formal Response to Kathryn Lynn Davis Complaint, submitted September 11th, 2019 p. 3

25 INDEPENDENT ETHICS AUDIT REPORT for Romance Writers of America, by Julia E. Judish Jerald A. Jacobs for Pillsbury Winthrop Shaw Pittman LLP. February 19th, 2020, p. 21

26 Report of the Ethics Committee, submitted December 11th, 2019, p. 5

27 INDEPENDENT ETHICS AUDIT REPORT for Romance Writers of America, by Julia E. Judish Jerald A. Jacobs for Pillsbury Winthrop Shaw Pittman LLP. February 19th, 2020, pp. 35–40

28 Ibid., p. 43

29 Ibid., p. 10

30 Ibid., p. 31