Human Rights

Upholding the Jihadist's Veto

The Court’s decision therefore constitutes a clear and present danger to the emerging consensus that blasphemy laws are incompatible with international human rights law.

In his provocative essay The Age of Reason, Thomas Paine didn’t mince words on Christianity. ”What is it the Bible teaches us?” he asked, and answered: ”rapine, cruelty and murder. What is it the New Testament teaches us?—to believe that the Almighty committed debauchery with a woman engaged to be married; and the belief of this debauchery is called faith.”

In 1819, the English deist Richard Carlile was convicted of blasphemy and sentenced to two years in prison for selling The Age of Reason.

Today Tom Paine is celebrated as one of the Enlightenment’s foremost champions of human rights. But even 200 years after his conviction Carlile might not have been vindicated had he been able to take his case to the European Court of Human Rights. In a recent ruling, the Court upheld the conviction of an Austrian citizen for an ”abusive attack on the Prophet of Islam which could stir up prejudice and threaten religious peace” for denouncing the Prophet Muhammad as a “pedophile.” The Court insisted that the comments could arouse “justified indignation” in religious believers who have a right to have their religious feelings protected. Moreover, states have wide discretion to prevent such “improper attacks on religious groups” in order to ensure social and religious peace. Paine would have been shocked and horrified by such logic. And it is deeply regrettable that the Court declined to revisit its long-held doctrine that the freedoms of religion and speech are conflicting rather than complementary rights.

Paine’s scathing attack on holy scripture was clearly offensive to many Christians—US President Theodore Roosevelt later called Paine “a filthy little Atheist.” But the harsh attacks on the authority of religion by Paine and other Enlightenment figures contributed to a broadening concept of tolerance encompassing both the right to express, critique and reject religious doctrines. So the Court’s insistence that the freedoms of religion and speech are in conflict when the latter is used to attack the former is regressive, however noble the purposes of securing “social peace” and “tolerance.” The Court’s reasoning is ultimately based on protecting the secular aim of peaceful co-existence rather than religious doctrine. But the underlying idea that expressions offensive to religious dogma constitute a threat to the social and religious peace of society has deep roots stretching back centuries.

This was the very basis of the Roman Inquisition with its Index of Censorship from 1559 which aimed at protecting the faithful “from the poison, the danger of infection, the corruption springing up from bad books and writings.” The last execution of the Spanish Inquisition did not take place until 1826 when the deist teacher Cayetano Ripoll was hanged in Valencia. Avoiding the spread of infectious ideas was also behind John Calvin’s burning of Michael Servetus in Geneva in 1553 for “lacerat[ing] the sacred name of God.” But not all Christians accepted that social peace demanded religious uniformity and coercion. In the early 17th Century, English Baptists such as Thomas Helwys and John Murton protested the systematic religious intolerance of England under King James I:

For men’s religion to God is between God and themselves. The king shall not answer for it. Neither may the king be judge between God and man. Let them be heretics, Turks, Jews, or whatsoever, it appertains not to the earthly power to punish them in the least measure.

Both Helwys and Murton died in prison for their principles.

The gradual acceptance that freedom of conscience is the foundation rather than a threat to religious peace and co-existence is therefore one of the most important and consequential ideas of Western democracy and has benefited religious believers as much as nonbelievers.

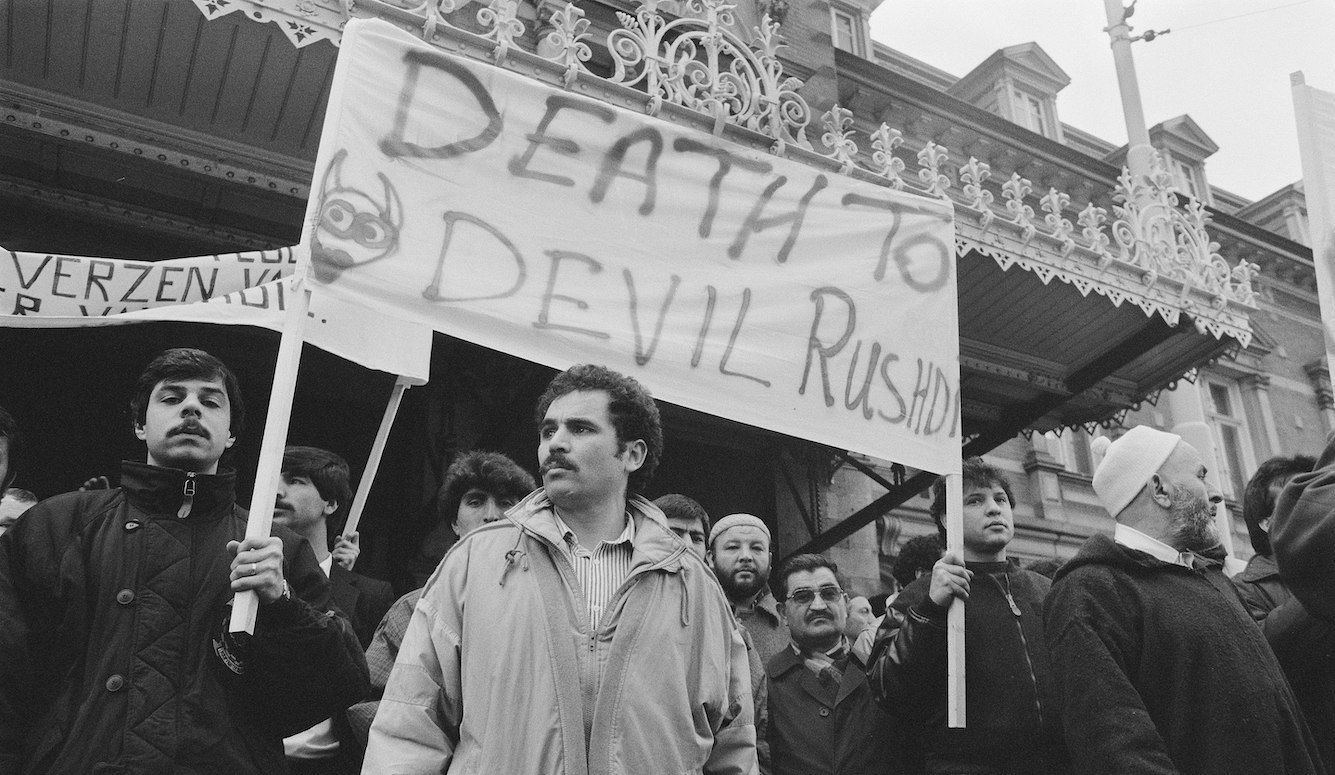

This remains true today. There is ample evidence to debunk the claim that laws against blasphemy are a necessary and effective tool for ensuring social peace. The vast majority of European democracies have abolished their blasphemy bans without an increase in religious conflict, unrest or violence. And those who do seek to enforce the “Jihadist’s Veto” by killing and threatening journalists and authors in Amsterdam, Paris and Copenhagen, should not be rewarded for their efforts. Enforcing blasphemy bans is neither a sign of progress and tolerance nor likely to appease religious extremists.

That lesson should be clear from a number of Muslim majority countries where blasphemy laws contribute to more, not less, extremism and violence. In 1992, Egyptian secularist intellectual Faraq Fouda was condemned as a blasphemer by a council at the Islamic Al-Azhar Islamic for mocking Islamist ideology and pointing to dark chapters in the history of Islam. Shortly thereafter, he was murdered by Islamists. Subsequently, Al-Azhar university not only blamed Fouda for his own murder but also banned Fouda’s complete works.

In a 2015 study, Amjad Mahmoud Khan from UCLA found that:

In Pakistan, Indonesia, and Nigeria—as may be true of other countries with anti-blasphemy laws—terrorism and blasphemy are inextricably intertwined. (…) The blasphemy criminal apparatus can embolden terrorists to commit crimes against humanity with impunity. (…)Efforts to repeal or reform such laws can be a critical step in delegitimizing the most dangerous organizations in the world.

Human rights organizations including Amnesty International, Freedom House and Human Rights Watch, have also noted that blasphemy laws are being abused to target religious minorities, dissenters, and to legitimize vigilant mob violence. Human rights discourse should play no part in providing legitimacy—however indirectly—to such practices.

The critical comments about the Prophet of Islam were based on accounts of the life of Muhammad in the Hadiths which next to the Qur’an are the most important foundational texts of Islam. According to some hadiths, the 53-year old Muhammad married a girl named Aisha at the age of six and consummated the marriage when she was nine.

A millennium before the Rights Revolutions that brought basic rights to (some) women and girls, child marriages were common in many parts of the world. So judging a 7th-century figure by the standards of the 21st century looks like bad history lacking proper context. But since Muslims claim Muhammad is the seal of Prophets, whose life is an example to follow even today, debating the merits and moral nature of his acts and sayings remains deeply relevant. Especially since modern secular states like Denmark, Norway and Sweden have debated allowing child marriages of asylum seekers out of “respect” for traditional culture.

Accordingly, the Court’s insistence that verbal attacks on religious doctrines and figures should have a certain “factual basis” creates an impediment to rigorous and passionate debate of religion. Much contained in texts considered sacred by their followers will be rejected as falsehoods by those of other faiths or non-believers. Moreover, to the non-believer, the Quran—like the Bible—includes many contradictions and even fervent believers passionately disagree about the correct interpretation. Hence, the numerous different sects each insisting that their interpretation of scripture is The Truth. When it comes to the life of Muhammad, historian Tom Holland has made the important point that almost no textual record appears until almost 200 years after Muhammad’s death.

Accordingly, no reliable standard of “factual basis” can or should be required for any opinion on religion or religious figures, however offensive to those who hold such doctrines or persons to be sacred. In the words of Jonathan Rauch, “A society which has accepted skeptical principles will accept that sincere criticism is always legitimate. In other words, if any belief may be wrong, then no one can legitimately claim to have ended any discussion—ever. In other words: No one gets the final say.”

It is this principle of “liberal science,” which the Court’s reasoning rejects by accepting only a benign interpretation of the life of Muhammad as The Truth. While the bloody and repressive aspect of religious intolerance has mostly been abandoned in democratic Europe, religious doctrine still trumps the conscience of the individual in many parts of the world. Blasphemy and apostasy is punishable by death in 13 Muslim majority countries. In Russia, artists, bloggers and YouTubers have been prosecuted for mocking religion under that country’s nebulous law against offending religious feelings. As the Court’s ruling stands, it might well have accepted the conviction of the Moscow Sakharov’s Museum’s curator and director for organizing an exhibition titled Religion, Be Careful!

The Court’s ruling does not mean that European countries are obliged to adopt blasphemy or religious insult laws. But it does suggest that if the editors of Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten and French magazine Charlie Hebdo had been convicted for publishing mocking cartoons of Muhammed, they would not have been protected by free speech. And the decision will almost certainly embolden authoritarian governments in the Muslim world and elsewhere to renew efforts to erect a global blasphemy ban. From 1999 until 2010, Muslim states in the Organization of Islamic Countries (OIC) supported by Russia and others attempted to include a ban against “defamation of religion” in international human rights law. Only a sustained effort led by democratic states, international organizations and activists defeated the effort. Since then the UN’s Human Rights Committee has clarified that “Prohibitions of displays of lack of respect for a religion or other belief system, including blasphemy laws, are incompatible” with the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

Even the very organization to which the Court belongs has distanced itself from blasphemy laws. In April 2017, Council of Europe Secretary General Thorbjørn Jagtland emphasized that “blasphemy should not be deemed a criminal offence as the freedom of conscience forms part of freedom of expression.”

Moreover, in the past ten years a number of European countries including Denmark, Norway, the Netherlands, the UK, Malta, and most recently, Ireland, have abolished blasphemy bans, leaving only a handful blemishes on the map of democratic Europe. The Court’s decision therefore constitutes a clear and present danger to the emerging consensus that blasphemy laws are incompatible with international human rights law.

The Court’s decision will also blunt criticism of existing blasphemy bans in countries where they’re used to marginalize minorities and punish dissent. Why should Pakistan, Russia and Saudi Arabia feel any pressure to abolish their blasphemy bans when the top human rights court in democratic Europe has blessed the idea that religion can be protected from offense without violating free speech?