History

Populism and Nostalgia's False Promise

Fear of individual and cultural extinction is both a cause and a product of the nostalgia so widespread in both Europe and America today.

Yuval Levin’s book The Fractured Republic and Andrew Brown’s essay on Trollhätten in Granta recount how Western societies have moved from a conformist and consolidated culture to a diffuse but bureaucratically centralised one, paralysed by gauzy nostalgia for a time that is never coming back. Such nostalgia has helped fuel the populist surge seen across the West today. The present poses challenges to who we are, how we behave, what we believe and how we act out those beliefs in everyday life. But the wish to return to the past is perhaps an inherent part of the human condition, and one that must be resisted lest it disfigure our perceptions and control our actions too greatly.

The populist revolt symbolised by the surge across Europe by parties like the Sweden Democrats and in America by Donald Trump is both a product and driver of a kind of nostalgia that risks trapping us in a spiral of longing and bitter disenchantment. It represents a backlash against an ossified establishment nostalgia that has failed to deliver on its promises, but also a symptom of a separate longing for its own version of a world that is no more. The past is to be remembered not lived in. Unfortunately, its powerful if illusory allure transfixes many in the West today.

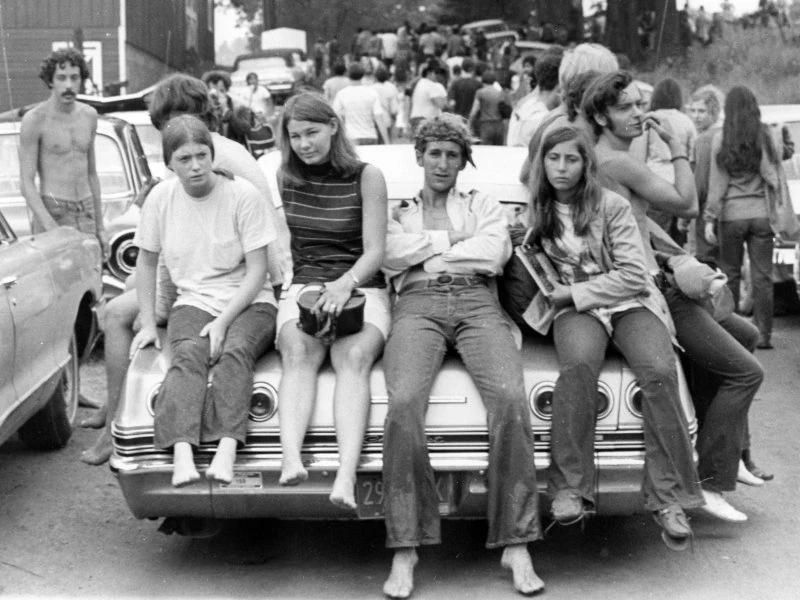

These trends form the basic thesis of The Fractured Republic. From the mid-20th century, the conformist mass participatory culture that dominated until the early 1970s has been steadily diffusing, atomising, and dividing people with differing beliefs, desires, ideas, and values into political and ideological silos. Concurrent with this rapid increase in individualism has been a massive increase in concentration and centralisation, both in government federal institutions and in the distribution of certain socio-economic groups. For example, the richer, highly mobile, more liberal, and more entrepreneurial elites now cluster on the coasts and in certain cities. Everyone else, meanwhile, resides in the hollowed out middle, and this hollowing out has occurred geographically and hierarchically.

As Levin persuasively argues, America’s current crop of politicians – be they populist or establishment – are handicapped by nostalgia for contending times of conformity. The Left longs for a time of worker solidarity and mass employment, high taxation, wage parity, and business cooperation with corporatist government. It yearns for the social radicalism of the Civil Rights Era, and earlier progressive moves to deal with the social and economic ills that the Left views as the plague of the underdog. For the Left, the golden age ran from around the end of WW2 through to the mid-1970s.

The Right, meanwhile, do not miss the prevailing economic doctrines and realities of those years, seeing them as emblematic of the Left’s infatuation with technocratic social-democracy, or socialism-lite, and the suffocation of economic dynamism. Instead, they miss a lost social order of the 1950s, and the conservative renaissance of the 1980s, when (in their telling) Ronald Reagan strode into the White House and rekindled the spark of economic and social dynamism snuffed out by 1970s stagflation.

Politicians (and their voters) on both sides want to hasten a return to their respective golden ages. It is no coincidence that many who bewail the current state of America are politicians and voters from the Baby Boomer generation. For them, not only is their preferred version of the post-war era imbued with a mythical transitory glory, but it also recalls memories of happy childhoods, made to seem all the more wonderful by a sentimental longing for the innocence and joy of youth. Seen in this light, Trump’s rhetoric about the lost jobs and glories of the past, Clinton’s paeans to past protest movements and progressive triumphs, and Sanders’s longing for the more social-democratic America of the New Deal, all acquire greater clarity.

None of this is helpful. Observed from the outside, both Republicans and Democrats are floundering in their attempts to navigate the waves threatening to overwhelm us all in an age of rapid change. The emphasis on freedom from both sides – complete economic freedom on the Right and complete social freedom on the Left – is no good if, to paraphrase Jordan Peterson, it just leaves us bereft of meaning and drowning in what postmodern theorist Zygmunt Bauman called ‘liquid modernity,’ – “the condition of constant mobility and change . . . in relationships, identities, and global economics within contemporary society.” Without the knowledge, wisdom, and experience with which to swim towards dry land, we reverse course and swim backwards to the lost continent of yesteryear.

The populist backlash that elected Trump was indicative of many things, but high among them must be this tendency by many of his voters to view the past, in both social and economic terms, as something to be reclaimed at the expense of forward progress. Of course, such a return is impossible and to attempt it is to face eternal disappointment and the growing bitterness produced by inevitable disillusion and failure. Both Left and Right would do well to bear in mind that disenchantment tends to sour nostalgia and risk a fall into something darker.

* * *

It is this bitterness that can lead to the growth of an altogether uglier kind of nostalgia promised by the far-Right. This well trodden path is illustrated in Andrew Brown’s essay for Granta about the Swedish town of Trollhätten, which shows the dangers presented by an ostensibly benign longing for yesterday. The backlash represented by the Sweden Democrats arose from the disappointment produced by the failure of nostalgic dreams, and the cynicism they left in their wake. Like America and the rest of the Western world in the 20th century, Sweden was a society of stiflingly conformity that rapidly atomised, causing a breakdown in social solidarity and a weakening of economic, social, and political institutions.

Brown describes how this stormy mix of disillusion and disorientation was worsened by steadily increasing waves of migration from the 1980s on, which heightened the anxieties and tensions already roiling Swedish society. However, the expression of these anxieties and tensions was thwarted by Sweden’s so-called ‘Corridor of Opinion’ that demands all patriotic Swedes accept open borders as a sign of their country’s moral purity. The consequent suffocation of contrary and dissenting views has, until recently, been enforced by a kind of social etiquette from which one strays at the risk of ostracism.

As the American journalist Tim Pool has shown, this corridor of opinion was enforced with almost brutal social acquiescence and is now firmly instantiated in Swedish culture. From the outside, it seems to be the only way that Swedish society can cope with the changes of recent years. Rather than being exposed, scrutinised, and countered in the arena of argument, anti-immigration sentiments and wider discontent have been suppressed and so have festered, unaddressed. Of course, the complacency that results from enforced conformity led to the shocking realisation that not everyone in the country shared the officially prescribed views on migration policy, particularly when they began to be articulated in the political realm.

This handed Sweden’s populist party, the Sweden Democrats, an opportunity to tap into discontent among significant parts of the Swedish population. As a result of a slick campaign that saw banned television adverts take advantage of the online space to great effect, the SD entered parliament in 2010 with 20 seats, and increase that figure to 49 in 2015. This was partly due to new opportunities for communication, themselves a result of what writer Robert Colvile has called ‘The Great Acceleration.’ What “might have worked twenty years before,” Colvile wrote, “when the only source of national news was the newspapers and the television” now didn’t. By 2015, “there was a thriving underground of news sites spreading the Sweden Democrats’ message, and the official silence merely amplified their appeal to people rebelling against the culture of conformity around immigration.”

As Brown observes, the other parties were so unprepared for the popularity of the Sweden Democrats’ rhetoric on such a salient part of Sweden’s patriotic identity that they “united around a policy of complete denial. They refused to debate with the SD in public, so far as this was possible; refused to eat with them in the canteens and refused to pass legislation that was dependent on SD support.” This inability to confront the SD with an alternative platform of ideas demonstrates the lack of core beliefs needed to challenge the SD’s platform. Sweden’s establishment parties seem to be lost in the Sweden of yesteryear, and have not yet appeared to reconcile themselves to the changing views of sizeable parts of the electorate on issues like migration, patriotism, and Sweden as a country with its own national and cultural identity.

Fear of individual and cultural extinction is both a cause and a product of the nostalgia so widespread in both Europe and America today. In a time of great uncertainty, global upheaval, and rapid advances in technology accelerating the pace of modern life, there is much apprehension about what the future holds, and about what it could mean for all of us.

Nostalgia – the clinging to what is known about the idealised before – is one way of coping with the unpredictable, the unknown, the unexpected, and the unfamiliar. Unfortunately, in Europe, this nostalgia plays out violently in Maajid Nawaz’s ‘Triple Threat” of the neo-Marxist revolutionary fantasies of the Far-Left, the nativist fantasies of the Far-Right, and in the longing for the instantiation of the Caliphate among the continent’s 50,000+ Islamists. All hark back, unable and unwilling to look forward.

The Populist Right, Islamism & #RegressiveLeft: a triple-threat tearing Europe apart. My latest for @thedailybeast https://t.co/hAf39mgVSD

— Maajid (@MaajidNawaz) 15 February 2016

The Sweden Democrats look back to a time when Sweden was culturally and, yes, ethnically more homogenous. While concern about mass immigration and its current and future impact on one’s society should not be a cause for social and political censure, none of the rhetoric that comes from them, or other European populists like France’s Front National, offers any sense of how to reform to conserve. The SD’s sentiments and words are soaked in an aching desire to recover the world of yesterday; as the SD party secretary said: “Of course society has to change, but back then we had a solid base to change from.” This desire for an unrecoverable past lacks an inner life or a transcendent belief that might bind people together. The ideology of the Sweden Democrats, like many adherents of hard Right ideology, draw instead on idealised conceptions of the surface self as manifest in skin colour. In their own way, the SD’s ideological foundation is as soulless as that of the establishment they despise, and as representative of the emptiness that feeds and is fed by nostalgia.

As Brown notes, even now, after all that has happened, none of this can be openly discussed in Sweden without immediate and dire repercussions. And so, the Sweden Democrats are a reaction against a rapidly increasing pace of change that no one can discuss, much less escape. To Brown, SD members resemble “strangers in their own country,” seeming “even more exiled from the country of their birth and of their upbringing than are the refugees and immigrants they so resent.” While advances in communications enable immigrants to stay in touch with those they’ve left behind in their countries of origin, Sweden’s past is impossible to reach across the impassable barrier of time.

As in the America, Sweden’s politics are being pulled apart by the centrifugal forces of the modern world, a process of dissolution aided by an inability to let go of nostalgia. SD follow the same pattern, their own nostalgia tinted with shallow racialism. The efforts by Sweden’s political and media classes to suppress all heretical thought no longer work, and actually help to foment further polarisation. One side is made up of British analyst David Goodhart’s well-off pro-immigration “Anywheres” and the other of anti-immigration, less well off “Somewheres.” And, as in America, both are equally guilty of being in hoc to nostalgia’s pull towards denialism and myopia. From Brown’s essay, Sweden seems to represent Europe in microcosm and in extremis, and points to how far and how fast a society can go when nostalgia and its handmaiden, nihilism, are allowed to get out of hand.

Nostalgia is not healthy for our societies, our politics, or ourselves; it simply perpetuates the hole many of us have at the centre of who we are, draining us and leaving us unwilling and unable to face today or tomorrow. Why make the effort towards anything when one is lost in the land of shadows that the glories of the past inhabit? Why make the effort to engage in Burke’s conservation through reformation when trapped among the ruins of the dead? Instead, we are stranded in the underworld and cleaved from the roots of our traditions, because the glare of our own time reveals inadequacies that we no longer know how to counter, mitigate, or heal. This threatens to deny us the opportunity to discern a way to deal with an ever-changing present that threatens to pull us under, aided and abetted by post-modernism and neo-Marxism, and spread by social media.

The only way to deal with our current predicament is to reject nostalgia and re-engage in reason and judgement, so as to renew ourselves and our culture through dialogue. We have to hope to discover what our highest ideal is, both personally and as national communities, and thus aim for the highest possible good that comes from the search for truth. Only then can we revive the moribund structure of our civilisation, and only through the spoken truth can we reclaim some order from chaos and leave the seductive but poisonous allure of reactionary nostalgia behind.