Art and Culture

From Roosevelt to Trump: The Presidential Smile

“Character is the decisive factor in the life of an individual and of nations alike.” And what better marker of character is there than a smile?

Sometimes the little things are really the biggest.

It may come off as a paradox, but nowhere is this truer than in that palace of power, the White House. When it comes to American Presidents, kinks and quirks can reveal more about the kind of leaders they are than heavy biographies and dusty archives. Scrutinising a President’s demeanour and bearing — with a keen eye and a perceptive mind — helps shine a glaring light on the virtues or failings of his character. As the 26th President of the United States, Theodore Roosevelt, once remarked, “Character is the decisive factor in the life of an individual and of nations alike.” And what better marker of character is there than a smile?

Smiling is a deceivingly simple act, perhaps even ubiquitous, yet it’s a highly expressive display of emotion. It’s immediately recognisable as a universal form of non-verbal communication, no matter the status or background of the recipient. So much so we don’t think when we see someone smile… we just feel. A smile is as much interpreted by the unconscious as it is produced by it. As such it becomes an effective mode of political communication, and a useful tool to gain further understanding of the men that led the free world.

In a 1962 lecture titled The Celebrification of Politics, French thinker Edgar Morin remarks that: “The Presidents of the United States make up a dynasty of smiles.” He tracks the Presidential smile from Franklin Roosevelt to then-President John Kennedy. To Morin, this distinctive smile is one of affability and friendliness. But if we’re to take a closer look, it appears indisputable there are as many smiles as Presidents. Roosevelt’s radiant beam is not Dwight Eisenhower’s giddy grin, itself a far cry from Richard Nixon’s awkward smirk. What’s more, these differing smiles do not arise in us the same passions. Morin, however, is correct: The smile is a significant strand in the symbolism of the modern American presidency. He’s not alone in making this observation. Roger Stone, the colorful and brilliant political strategist, likes to quip: “Politics is show business for ugly people.” And isn’t the first rule of show business — echoed by impresarios and photographers alike, abided by the movie stars of yesteryear and the celebrities of Instagram — SMILE?

Franklin Roosevelt is the first American president to smile. Not literally, of course, but Roosevelt makes smiling a compulsory requisite for the top job. It’s easy to see why. Roosevelt’s smile is therapeutic. It lights up his chiselled face, draws attention to his piercing gaze. It’s simultaneously whimsical and heartfelt. In 1933, the year Roosevelt ascended to the Oval Office, America had nothing to smile about. It was a weary nation plagued by the scourge of the Great Depression. Famine could be found at every street corner, the hopes for recovery had slipped into darkness. That grim state of affairs was exactly what turned Roosevelt’s smile into a cathartic national experience. With Roosevelt America had found her messiah. His smile, then, was a show of defiance, a call for self-belief and a source of strength for the people. And no less than 25-year old Ronald Reagan — himself a future master of the optimistic smile — found solace in the awesome power of Roosevelt’s beam. Years later, Reagan would remember: “It was in 1936, a campaign parade in Des Moines, Iowa. What a wave of affection and pride swept through that crowd as [Roosevelt] passed by in an open car (…) a familiar smile on his lips, jaunty and confident, drawing from us reservoirs of confidence and enthusiasm some of us had forgotten we had during those hard years.”

Roosevelt’s smile uplifted America because it was a manifestation of his character. It was not a show he put on for the cameras, but a personal discipline he had acquired in his struggle with polio. Roosevelt had undergone tremendous trials in his life, and he had overcome them through a simple belief, contained in his inaugural address: “There is nothing to fear but fear itself.” All challenges, in his mind, could be met so long as people did not let doubt cloud their resolve. His closest collaborators, too, were amazed by the positive certainty with which he conducted White House affairs. “There’s something that he’s got,” remarked Harry Perkins, a close advisor. “It seems unreasonable at times, but he falls back on something that gives him complete assurance that everything is going to be all right.” That something spread, almost magically, across the land. Roosevelt’s smile was its symbol. Perhaps no one has captured the Roosevelt mystique with more poetic accuracy than Albert Camus, who observed: “He had the face of joy. He knew there is no pain that cannot be overcome by energy and conscience.”

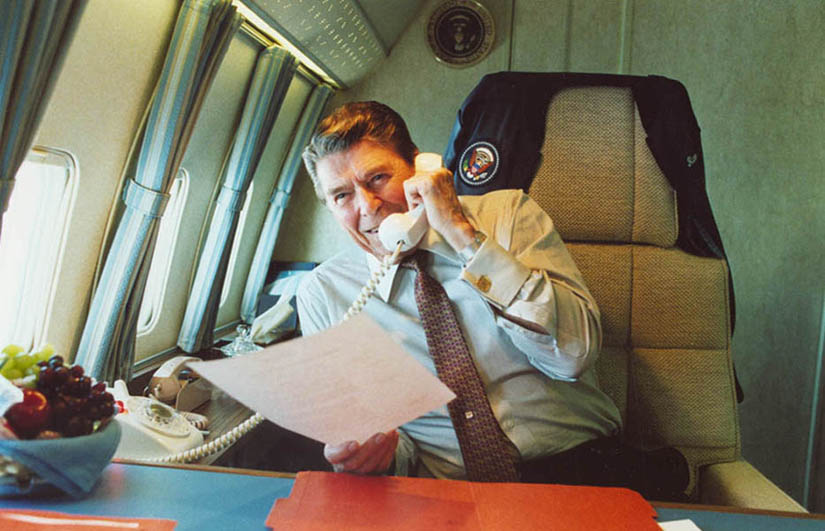

Ironically, the heir to the Roosevelt smile is the President who dismantled his legacy, Ronald Reagan. Reagan had a disarming smile. It was gentle and charming. Coupled with a soft-spoken joke, and a twinkle in the eye, it made anyone forget their plight.

Its effect was two-fold: It diffused the heaviness of the economic recession America faced and, after the bleak 1970s, it hinted at happier days ahead. To see Reagan smile — in close-up on the television set — was also to share a moment of cherished intimacy with the Commander-in-Chief. Even though he was addressing over two hundred million Americans, Reagan acted as if he was speaking to just a single individual. And he smiled that way too. His eye glimmered with goodness, forging plethora of personal connections. Americans felt like Reagan understood them. There again, as in Roosevelt’s case, this ploy was effective precisely because it was not one. Reagan, no matter what might be said about his politics, cared about (the) people. He was not selfish, and he showed everyone grace and magnanimity.

Peggy Noonan, one of his speechwriters, recalls in her memoir What I Saw at the Revolution: “He answered letters from citizens with the same kind of care and respect that he gave a letter from [British Prime Minister Margaret] Thatcher or [West German Chancellor Helmut] Kohl.” Countless other anecdotes fuse: Reagan sending checks to strangers and friends alike; inviting his pen pals to visit him in the Oval Office, to the disarray of his staff; keeping the pictures ordinary families sent him in his suit pockets. That regard for his fellow men, that spirit of altruism pervaded through his smile in a throwback to the good-hearted populism of Old Hollywood. After all, Reagan had been in the movies… even if he was never a major star.

If the smiles of Roosevelt and Reagan each redeemed the soul of America, what about the other Presidents?

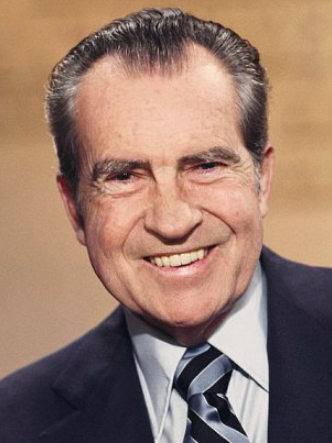

Harry Truman’s, like George W. Bush’s, expressed bonhomie and the promise of a cheerful time. Their smiles arch back to the archetype of the good neighbour, who cracks cheesy jokes and likes to talk sports. Their jejune grins may not foreshadow scintillating intelligence, much less strength of character, but they make them appear approachable and commonsensical. At the opposite end of the spectrum lie Lyndon Johnson and Richard Nixon: The sinister kings of the Presidency. Johnson’s smile, so much as he has one, is treacherous.

It’s the sneer of the consummate politician who revels in the suffering of his foes, and exults in the expansion of his own power. It’s the snigger of the pervert who likes to make his aides watch on as he defecates. Or it’s the greedy roar of “the animal,” as Richard Nixon once derided his rival. Nixon, meanwhile, smiled because he felt perpetually uneasy. His smile betrayed his existential crisis, that of a man and a President growing out of touch with reality, submerged by the social upheavals of the day, enslaved by the neuroses he struggled to make conscious. To watch Nixon smile, then, is not to be reassured — as with Roosevelt or Reagan — but rather to be reminded of man’s seemingly limitless capacity for self-loathing and mental desecration. The smiles of Johnson and Nixon are two displays of political corruption: one triumphant, the other defeated.

What about John Kennedy, the President that preceded Johnson and Nixon and, in many ways, supersedes them in public memory — an icon of dash and audacity? John Kennedy had a glamorous smile. In the 1960s, he was a new kind of man, bold and adventurous: The living embodiment of his “New Frontier” slogan. Kennedy was sexy, and his impish smile showcased both the panache of the philanderer and the nobility of his New England roots. There is — we think — a man racing through life, chasing the horizon. A man to follow, at ease with himself… or is he? Stare long enough at Kennedy, and his debonair smile turns into a painful rictus. The smile appears rehearsed, fixed, like a mask worn to hide one’s true feelings.

In fact, Kennedy had been ill his whole life. As a child, he spent months in the hospital for various intestinal disorders and infections. As an adult, he suffered from ulcers, colitis, Addison’s disease and degenerative, severe back trouble. He was perpetually on a cocktail of pain killers, anti-spasmodics, steroids and injections. Life was not a playground for the young president. What’s more, Richard Nixon —proving to be considerably better at reading others than himself —observed: “John Kennedy was quite a shy person. It was not easy for him to get out and shake hands. He did it very well, but he was a quite private person.” Kennedy, it turns out, is a man that did not enjoy himself — plagued since childhood by family drama and personal woe. His smile, thus, in some strange way foreshadowed his demise, painting him as an aspirational but ultimately doomed figure out of Greek tragedy, a shining prince somewhat too whole — and intrepid— for the world. Kennedy’s smile was just too great to be true…

Bill Clinton, who sought to emulate the Kennedy smile, never reached those heights. Despite his best effort, his always remained the sly smile of the small-town car salesman hell-bent on making it big. We sense he’s cheating us out on the merchandise, but he’s just so damn gregarious so we go along with it. George Carlin joked: “Clinton may be full of shit, but he lets you know it!” When Clinton smiles, it’s engaging because we feel part of his club. He’s the popular guy in high school, not actually likeable though we want him to like us. His smile is the way he achieves that connection.

Meanwhile Barack Obama, the Democratic president that entered office eight years after Clinton, has the smile of a Hollywood A-lister. He summons his elated grin at a moment’s notice and the effects are devastating. We just melt. Watch, in particular, the way Obama makes the smile appear on his cheeks. It takes a few seconds to broaden, the muscles slowly flex. It’s long enough for us to understand what he’s doing, at least subconsciously, and foster expectation.

By the time the grin has reached Obama’s ears, we feel satisfied. As his Presidency proceeded, losing momentum and purpose with every passing year, the smile lost some of its appeal. Obama was a shadow of his former self, an automaton going through the motions. Like Bruce Willis playing the sardonic cop one time too many: The performance turned stale. Obama could crack the smile, but it would never have the same effect on us. We could tell he was tired, disappointed. That he no longer felt the audacity of hope. The toll the Oval Office had taken on him was considerable, and he had the candour to show it. Jimmy Carter and Herbert Hoover did too: Unlike Obama their smiles were never good, but like him their afflicted selves were never really bad. It all terribly lacked inspiration. And in politics, as in show business, the cardinal sin is boredom.

But we didn’t stay bored for very long. Someone straight out of show business took the show on the road. Donald Trump is perhaps the most expressive of U.S. Presidents. He has not one smile but dozens. To understand why that is, we must first probe what sets Trump apart. He spent a decade on the small screen in a very strange and innovative genre known as reality TV. Reality TV works mainly as a combination of rapid one-liners and three-second “reaction” shots — showcasing, in close-up, the facial reactions elicited by the one-liners. Since the editing pace is brisk, each expression must be very easy to read. There can be no ambiguity, no attempt — as an actor would — at appearing natural. This is why in an interview Trump switches facial expressions in a matter of seconds, from surprise to elation, resentment to glee, all without a clear through-line or a logical sense of emotional progression. In Reality TV, that part of the job is done not by the performer… but by the editors arranging the material after the shoot. That’s not to say Trump is not successful at communicating meaning with a smile. He is — if only you see him as the first emoticon President, telegraphing his mood with the same brashness he displays on social media. A recurring Trump smile is the wide toothy smile, which he resorts to when posing with a fellow world leader or standing in front of the American flag. It’s enthusiastic, bigger-than-life and sure to bolster his supporters.

An idiosyncratic Trump smile is what psychologists call the “zipped smile.” His lips are sealed, his head slightly lowered. The corners of his mouth look as if pulled from the outside. This very odd smile is used to express disbelief. It’s the “Fake News” smile — which Trump made extensive use of during the debates. It’s a strong reaction shot: iconic and easy to turn into social media “memes.” The smile pleases the base while, even more importantly, getting under the skin of liberals. Trump does not smile to unify but to settle scores, wage fights and, in true reality TV fashion, rack up ratings.

For the past decade, America has been stuck in a bottomless crisis. The greatest financial shock since 1929 has unleashed carnage on the once-prosperous nation. Life expectancy has decreased, inequality has risen, drug epidemics have flourished. Public faith in government has depreciated. Private monopolies have solidified their stranglehold of the economy. The establishment and the media are hated. Foreign wars are perpetual debacles. People on both the left and the right are retreating into ever-narrower groups. Identity politics has made a resurgence — and with it outrage which begets censorship, and, inevitably, violence. Above all, the American people are scared to death. The last time America was in the throes of such terror, a President rose up and asserted his “firm belief that the only thing we have to fear is fear itself.” In so doing, Franklin Roosevelt made America great again. In the words of Ronald Reagan, who too ordained a renewal in national sentiment: “As someone who has served in the office [Roosevelt] once graced so magnificently, no higher tribute can be given a President than that he strengthened our faith in ourselves.”

There will only be one Roosevelt but perhaps we can heed his precedent — and remember that the works of repair and reform begin not with words or policies… but with a smile.