China

Liberal Democracies Should Open Their Doors to Hongkongers

Accepting Hongkongers into our countries would be good for us.

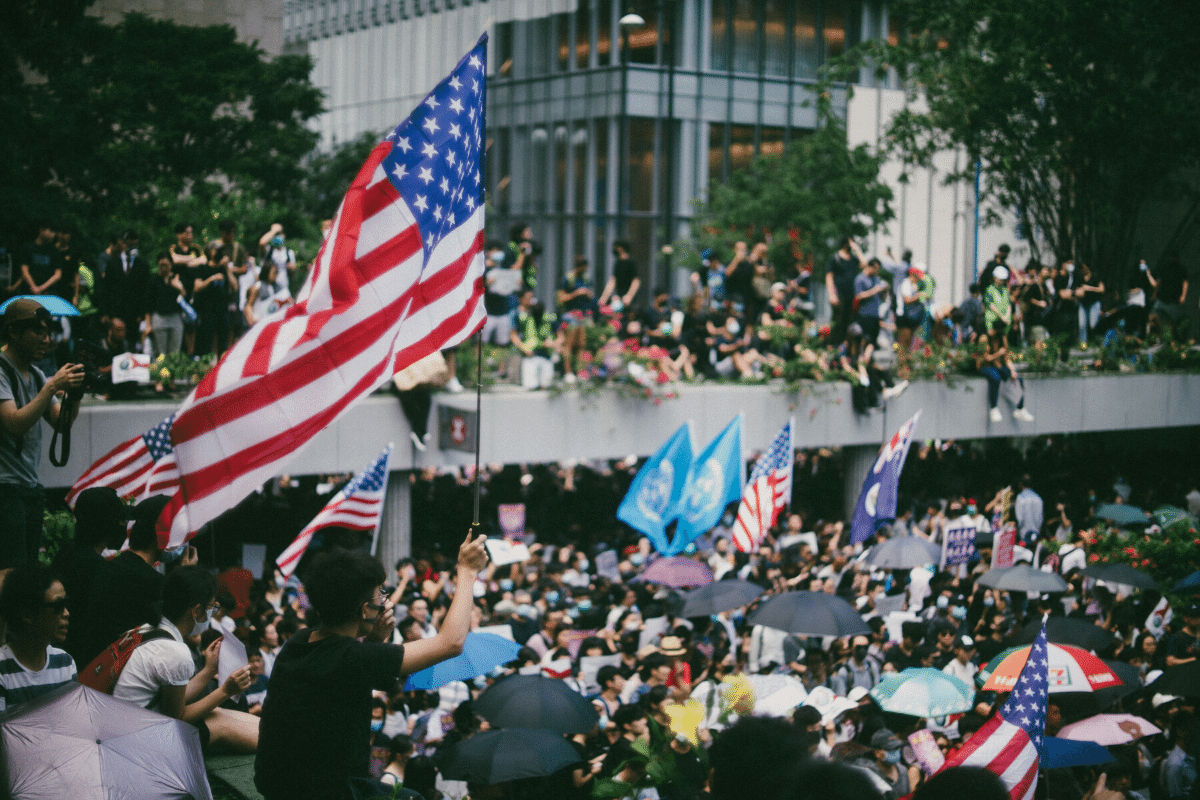

A year ago in March 2019, riots broke out in Hong Kong over concerns that a Beijing-backed piece of legislation would allow Hongkongers to be extradited to mainland China. Fears are that the law would be used to target pro-democracy advocates and anyone critical of the Communist Party of China (CPC) regime; exposing them to the notorious injustice of the mainland Chinese courts. China has long maintained a conviction rate of over 99 percent, which to the naïve might look like an incredibly efficient justice system—so thorough in its criminal investigation that no charges are laid until guilt is virtually certain—but is in actuality an indication of government control over the judiciary where verdicts are decided before the trial even begins. This in contrast to the legal system in Hong Kong, which is based on common law inherited from the British, and includes all the familiar features we would recognize in our own legal systems such as, “equality before the law; freedom of movement; freedom of conscience and religious belief; freedom of speech; and privacy of communication.” Residents of the city believe—correctly—that the new law represented an unacceptable curtailment of their freedoms.

Due to months of protest, eventually the Hong Kong administration, which is headed by Carrie Lam (who is supported by mainland China and has been accused of essentially being a puppet for the CPC) backed down and said that the law would not be implemented at that time. As a result of further protests, the extradition law was eventually scrapped in October, but this was seen by many as “too little, too late.” Protests have continued with varying intensity ever since, with other demands including the implementation of universal suffrage for Hong Kong. In May of this year, a new security law with far more sweeping powers was tabled by Beijing, which has added additional fuel to the continuing protests. Unlike last year where the mainland took a more hands-off approach, this time they made clear their intentions to ram the legislation through regardless of objections in Hong Kong or international outcry. The law was given final approval on Tuesday, June 30th, the day before the anniversary of the 1997 handover of Hong Kong to China by the British. Among other things, any form of dissent appears to be banned, with “Crimes of secession, subversion, terrorism and collusion with foreign forces… Inciting hatred of China’s central government and Hong King’s regional government” now carrying prison sentences ranging anywhere from three years to life. The effect of this will be to completely destroy the “One Country, Two Systems” framework, which was supposed to grant Hong Kong a large measure of self rule until 2047.

Beijing’s increasingly hard-line approach has elicited international condemnation from liberal democracies such as the US, UK, Australia, the EU, and Canada. Unfortunately, these seem to have done little in China except elicit statements that everyone else should mind their own business and stop interfering in China’s domestic affairs; indicating once again that China is far more interested in exerting control over territories it considers its own than worrying about international reactions. And really, why should it? After Russia annexed Crimea in 2014 and its continued military adventuring/involvement in eastern Ukraine, the only international reactions have been finger-wagging and some economic sanctions. A relatively small price to pay if your goal is empire building.

Over the past few decades much of the world has been trying to push China towards becoming a good-faith actor on the global stage; and to integrate China into the system of trade and laws that govern normal international relations. This was especially the case in the 70s and 80s when China’s relationship with the United States made steady progress, and again in the early 2000s when the Clinton administration opened a path for China to join the World Trade Organization. The hope was that by interacting economically with relatively free and open societies, corrupt or authoritarian nations such as China would acquire not only a freer market, but also the other trappings of liberal democracies; such as democratic elections, rule of law, freedom of speech and a respect for individual rights. While there have been many successes of such “peace through trade” policy—including success stories like Botswana and Chile—China seems to be the exception that proves the rule. Unfortunately, because of its size and economic power, it’s a powerful exception; one that is impossible to ignore. Given the unlikelihood of China reforming towards a more free and tolerant society anytime soon, and given its desire to exert its freedom-supressing influence on Hong Kong, other options must be considered. Of which perhaps the most appealing and expedient is for countries that value freedom to invite the residents of Hong Kong to emigrate.

Britain has taken the lead by announcing that Hongkongers holding a British National Overseas (BNO) Passport will be allowed to live and work in the UK for five years, after which they can apply for settled status—and one year later, citizenship. Which could mean almost three million people able to relocate to Britain if they so choose. In response to earlier British overtures along these lines, China made clear in no uncertain terms that Hong Kong is their concern, and that the UK should mind its own business; with China’s foreign ministry spokesman Zhao Lijian saying that the “UK has no right to lecture or interfere in China’s internal affairs…”.

However, a BNO Passport is only available to Hong Kong residents born before the 1997 transfer of the city back to Chinese control; which leaves around 4.5 million of the city’s residents—including many of the younger generation born after the handover occurred—unable to access that option. Which is why this sort of idea must be expanded on more broadly by all liberal democracies, who should consider granting special dispensations allowing Hong Kong residents who wish to emigrate to do so. Australia and the United States are considering following Britain’s example, and hopefully they are just the first of many.

It wouldn’t be the first time liberal democracies have taken in a large influx of exiles from specific countries. Consider the influx of refugees which started with the Boat People, who originally were mostly South Vietnamese fleeing after the US pulled out of the war and their country fell to the communist north. They, and many more from other south-east Asian countries who fled their homes in the 1970s and 80s, many ending up in Western nations. The United States took in the majority, with Canada, Australia, and a few others accepting large numbers as well. Another recent example is the refugees from the ongoing Syrian conflict. While it’s true in this case that the majority ended up fleeing to nearby countries, large numbers came to Western nations as well; particularly Europe.

There are some major differences however when it comes to opening our doors to residents of Hong Kong who wish to leave the increasingly oppressive rule from Beijing. Unlike many who flee war-torn or poverty-stricken nations searching for a better life, Hongkongers are among the most educated and wealthy people on the planet. Most important though, many of them love freedom, and have grown up in a society where many of the things we claim to value—rule of law, personal liberty, freedom of conscience, free speech, and a free market—are paramount. Or were.

Accepting Hongkongers into our countries would be good for us. It seems that in the last few decades liberal democracies have been growing complacent about our hard-won freedoms. We have forgotten or ignored history, and seem not to realize the foundations on which our freedoms are built need constant maintenance and defense. Because of our complacency, there is a growing illiberal element in many of our countries; people who think feelings trump facts, or that words are violence. Or even that socialism is good, and capitalism bad. All beliefs and attitudes unlikely to be present in Hong Kong residents who wish to flee authoritarian rule. Western countries could use a shot in the arm of freedom; and a sizable influx of people who have had to fight for and fear the loss of their freedoms will perhaps help remind us of what we have and why it’s precious.

Obviously, welcoming Hongkongers into our countries isn’t just good for us, but also—and perhaps especially—for them. We will give them a place to enjoy their freedom and to live their lives unafraid of being jailed for criticizing the government or not toeing the party line. Places where they can vote to affect the course their lives and their country will take; and where they can fight to preserve freedom in a setting where they have a far better chance of winning; and where they won’t be tortured or killed for their troubles.

While nothing is written in stone, it seems like Hongkongers’ fight to retain their freedom in the city they love is a losing one. China is just too big and too close for the citizens of Hong Kong to win their fight to stay out from under the Communist Party of China’s thumb. Even in the best-case scenario, their freedom had an expiration date of 2047. With the passage of this new security law, things have become more dire. Perhaps the time has come for freedom-loving residents of Hong Kong to get out while they still can. It is our duty and privilege as liberal democracies to give them sanctuary; and if we do, we can expect a better future for them and for ourselves.