Art and Culture

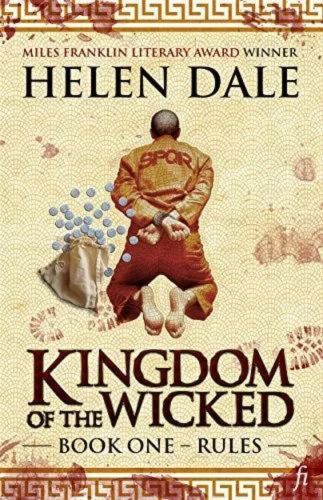

What if the Industrial Revolution Happened to Rome?

What, I wondered, would have happened had Jesus emerged in a Roman Empire that had gone through an industrial revolution?

My novel Kingdom of the Wicked — Rules took me 13 years to write. It has been a long time between drinks. Rules isn’t all of it, either. Book II, Order, comes out in March, so apologies for the cliffhanger.

However, rest assured I haven’t gone all George R.R. Martin on you. Everything is written, with only final editorial to complete.

I’m aware many people neither expected nor wanted me to write anything after The Hand That Signed the Paper. To those who wanted me to shut up and go away, I’m here to tell you while I went away (I have become one of those irritating expatriate British-Australians), I have no intention of shutting up.

Two years after The Hand That Signed the Paper was published in 1994, I began to research and write a historical novel set during the reign of the Roman emperor Vespasian. A local television station even flew me to Italy, allowing me the time and resources to do further research, in exchange for appearing on one of its programs.

There was one problem: the book I started to write was bad. I persisted for a while, thinking I could draw on what I hoped was developing literary skill to iron out the wrinkles. Unfortunately, the manuscript turned out to be all wrinkles, so I abandoned it.

The idea of some sort of Roman-era book never went away, however, and when Kingdom of the Wicked came to mind, demanding to be written, I knew the book I originally wanted to write was the wrong book. This, I hope, is the right one.

In between writing the two novels, I became a lawyer, and, consequently, Kingdom of the Wicked is a product of legal, rather than historical, theological, or scientific imagination. This isn’t to say that history, theology, and science aren’t important in the world I’ve written, but to highlight that the book began with law.

Let me explain.

While I was in my second year at Oxford, a friend asked me if I’d seen Mel Gibson’s Passion of the Christ. I had to admit I had not, and at his suggestion watched it. Leaving the immense controversy and success of Gibson’s film to one side, at its conclusion I found myself thinking about the Gospel accounts of Jesus’s trial and execution from a lawyer’s perspective. I realised I hadn’t read them for many years, and certainly not since qualifying in law. ‘If I were counsel, how would I make a plea in mitigation…’ is a favourite parlour game, although more commonly applied to errant footballers and wayward celebrities, not religious figures.

What struck me at once was the attack on the moneychangers in the Jerusalem Temple. All four Gospels record it, and their combined accounts do not reflect well on the perpetrator’s character.

Jesus went in armed (with a whip) and trashed the place, stampeding animals, destroying property and assaulting people. He also did it during or just before Passover, when the Temple precinct would have been packed to capacity with tourists, pilgrims, and religious officials. I used to live in Edinburgh, a city that has many large festivals. The thought of what would happen if someone behaved similarly in Princes Street during Hogmanay filled my mind.

It seemed obvious to me Jesus was executed because he started a riot. Everything else — the Messianic claims, giving Pilate attitude at trial, verbal jousting with Jewish religious leaders — was by the by. Our system would send someone down for a decent stretch if they did something similar; the Romans were not alone in developing concepts of breach of the peace, assault or malicious mischief.

In response, my friend suggested wryly, while Pilate was locking up the ringleader, perhaps the disciples each copped an anti-social behaviour order (ASBO). I laughed, but I also started thinking. How, I wondered, would we react to Jesus Christ if he turned up now?

My answer was not one I liked very much: I thought we’d mistake him for a terrorist. There was a period in the sixties and seventies when Jesus was conceived of as a bit of a hippy, certainly a pacifist. But the figure belabouring the ancient world’s equivalent of bank tellers with a whip did not look like a pacifist to me. Then there was his politics: socially conservative (he railed against divorce), redistributive, even socialist (he railed against the rich), egalitarian (he railed against the treatment of the poor). He wasn’t too impressed by the Great Satan of his day, the Roman Empire, either. His Judaean contemporaries referred to the Roman Empire as ‘the kingdom of the wicked’, whence the title of this book.

For a little while, I thought of transplanting Jesus to Britain or the US and watching the story unfold (and unravel) as I told it, but every single version that played out in my head turned into Waco or Jim Jones’s People’s Temple. Those stories are terrifying and confronting by turns—as well as fascinating—but they are not the stories I wanted to tell.

Finally, instead of bringing Jesus forward in time and placing him in modernity, I thought to leave him where he was and instead put modernity into the past. What, I wondered, would have happened had Jesus emerged in a Roman Empire that had gone through an industrial revolution? Other things being equal, what would modern science and technology do to a society with very different values from our own? Would they react with the same incomprehension that we do when confronted by religious terrorism? I did not know the answers, but I suspected that writing a book based around the idea of a Roman industrial revolution might help me develop some answers, if not the answers.

This meant I tried to conceive of a world where a society unlike ours produces the ‘progress and growth’ template that all others then seek to follow. It is commonplace to point out that Roman civilisation was polytheistic and animist, while ours is monotheistic but leavened by the Enlightenment; that Roman society was very martial, while Christianity has gifted us a tradition of religious and political pacifism; that Roman society had different views of sexual morality and marriage.

In short, I had to imagine an industrial revolution without monotheism or the Scottish Enlightenment. I could not stray too far from the West as we know it, however, for while we may have lost Rome’s ancestor worship, multiplicity of gods and goddesses, candy-coloured religious art (Roman statues and temples were brightly painted, as they are in Hinduism) and filial piety, Europe in particular has kept much of its law, and the great bulk of Roman law was conceived of and employed by polytheists.

Sometimes this non-Christian heritage is obvious: the toleration of homosexuality, abortion and concubinage, easy divorce, the importance attached to appointing an heir whose job it is to undertake regular ritual appeasement of ancestral spirits.

Sometimes, however, Roman law is different from the English common law only in its details. It also provides an orderly way of resolving disputes over everything from who owes money to whom, to who sideswiped whom. Both systems (and, in the context of human history, neither Roman law nor common law have any serious rivals as legal systems) were clearly developed by peoples with a genius for intelligent legal organisation and the ability to change bad law and retain good law. Both systems show a sophisticated understanding of the gains to be made from trade and the embedded nature of private property.

How, then, to create this mixture of familiar and foreign?

The best speculative fiction persuades you that its alternative world is real. It convinces you to suspend disbelief. It does this by constructing plausible points of departure from actual history.

In The Man in the High Castle (Philip K. Dick), Roosevelt is assassinated and replaced by a nonentity. In SS-GB (Len Deighton), Operation Sea Lion is successful. In Pavane (Keith Roberts), Elizabeth I is assassinated and the English Reformation doesn’t get off the ground. While I am more interested in working out the way people relate to each other and to society rather than in the intricacies of interlocking technical developments, I have been as careful as I’m able in constructing my points of departure.

Kingdom of the Wicked is also what Oxford University got instead of a DPhil in law. I was reading for one after completing my bachelor of civil law there. Producing a novel made it clear legal academe was not in my future (novels are great, but law faculties prefer 120,000 words on … law). My scholarship ran out (as they do); I went back into practice, continuing to write at night after work, using some of my more flamboyant colleagues and clients as raw material. Yes, it’s true — do not annoy the writer. She may put you in a book and kill you.

I was pleased I could still write fiction. After the book I started in 1996 crashed and burned, I decided that novels probably weren’t for me. I also continued to get a great deal of abuse — even while overseas — and had no desire to add to it. However, there’s no escaping the fact Kingdom of the Wicked demanded to be written.

There was a long period where I came home from work — whether tutoring or working as a corporate solicitor — and simply sat down and wrote. The completed manuscript was 300,000 words long and — as my publisher said — simply had to be divided into two books, otherwise only a hardback edition was viable.

My comments have strayed far from the story of Jesus and the moneychangers in Jerusalem’s Temple, but context is useful, if only to illustrate what interested me when I started writing.

I am wary of attempts to distil books into a single theme, but if there is one thing that exercised my mind while writing Kingdom of the Wicked, it is the relationship of the two missionary monotheisms, Islam and Christianity, to science, technology and the Western use of a form of religious tolerance that a pagan Roman would recognise but for a long time was in abeyance in the West and elsewhere.

Rather than attempt to say how that relationship should work in so many words, I used fiction to explore my own confusions, doubts and concerns.

This article was previously published in The Australian