Education

Are the Social Sciences Undergoing a Purity Spiral?

Haidt and others formed the Heterodox Academy, which is dedicated to arguing for a more intellectually diverse academy and now has almost 900 members.

A couple of years ago, six social scientists published a paper describing a disquieting occurrence in academic psychology: the loss of almost all its political diversity. As Jonathan Haidt, one of the authors of the paper, wrote in a commentary:

Before the 1990s, academic psychology only LEANED left. Liberals and Democrats outnumbered Conservatives and Republican by 4 to 1 or less. But as the “greatest generation” retired in the 1990s and was replaced by baby boomers, the ratio skyrocketed to something more like 12 to 1. In just 20 years. Few psychologists realize just how quickly or completely the field has become a political monoculture.

While the paper focuses on psychology, it briefly mentions that the rest of the social sciences are not far behind:

[R]ecent surveys find that 58–66 per cent of social science professors in the United States identify as liberals, while only 5–8 per cent identify as conservatives, and that self-identified Democrats outnumber Republicans by ratios of at least 8 to 1 (Gross & Simmons 2007; Klein & Stern 2009; Rothman & Lichter 2008).

As these studies are now approximately ten years old, it’s quite plausible that the gap has widened further over the past decade (as it has in psychology) meaning that these figures most likely underestimate the current left-to-right ratio across the social sciences.

In response to this problem, Haidt and others formed the Heterodox Academy, which is dedicated to arguing for a more intellectually diverse academy and now has almost 900 members.

One shouldn’t draw conclusions too hastily, of course, and there are many plausible explanations for this trend. For example, economist Paul Krugman argued on his blog that data suggests the Republican Party has moved rightwards over the past few decades, dragging with it the definition of a “conservative,” thus driving academics away from both the Republican Party and from conservative orientation.

Krugman suggests that this is especially true of scientists, even more so than non-scientist academics, due to a perceived hostility towards climate change data and evolutionary theory within the Republican Party. (He doesn’t distinguish social scientists from scientists in general. Although to be fair, the Heterodox Academy has marketed itself as addressing a general problem in academia.)

A more detailed examination by political scientist Sam Abrams doesn’t lend support to Krugman’s hypothesis. Abrams found that party and ideological affiliation has remained relatively constant among the American population over the past 25 years; while it has shifted markedly to the left among professors:

Professors were more liberal than the country in 1990, but only by about 11 percentage points. By 2013, the gap had tripled; it is now more than 30 points. It seems reasonable to conclude that it is academics who shifted, as there is no equivalent movement among the masses whatsoever.

What is particularly striking about this shift is that the number of moderates has dropped sharply among professors. This seems to be the strongest argument against Krugman’s hypothesis. If professors were driven away by a rightward shift in the Republican Party, one could reasonably expect a build-up of moderates. Yet, this has not happened at all.

In fact, Haidt recently reported on a remarkable survey that was conducted among the Society for Experimental Social Psychology, which, as Haidt notes, is:

… a professional society composed of the most active researchers in the field who are at least five years post-PhD. It’s very selective—you must be nominated by a current member and approved by a committee before you can join.

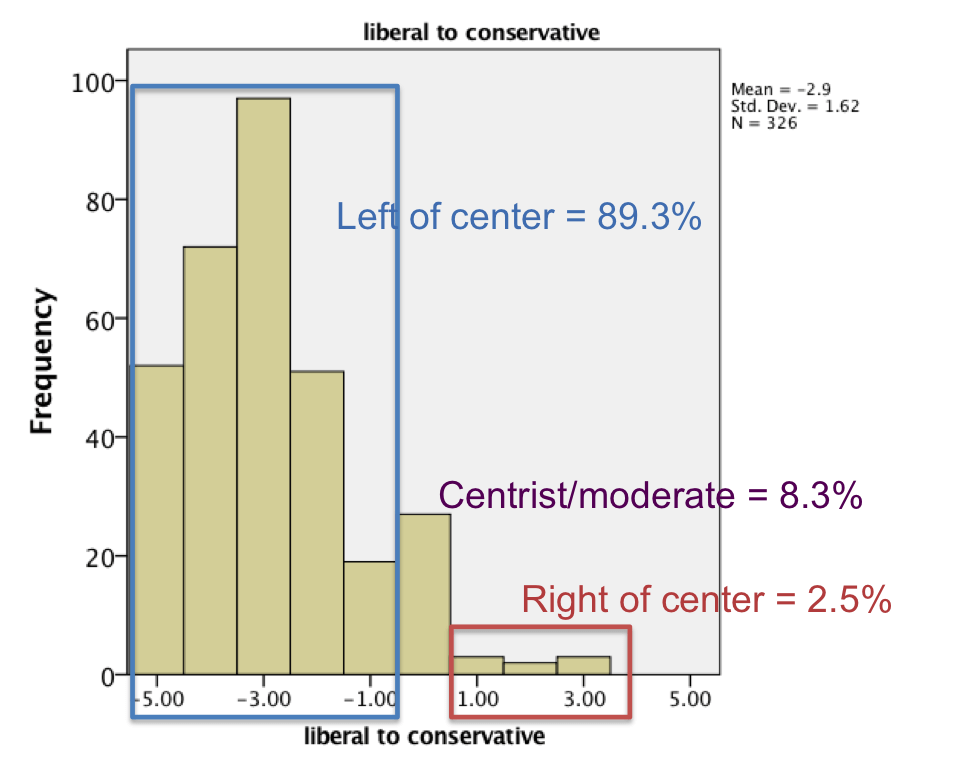

As part of the survey, members were asked to identify their political affiliation on an eleven-point scale, from ‘very liberal’ to ‘very conservative’. (One point in the centre and five on each side.) The results are telling. Only 2.5 per cent of respondents chose a conservative point, and only 8.3 per cent chose the centre-point, meaning that 89.3 per cent identified as left-of-centre.

Intriguingly, the least popular point among the left-of-centre points was the most moderate one (5.8 per cent), and the second-least popular was the second-most moderate one (15.6 per cent). More than two thirds (67.8 per cent) chose one of the three points furthest to the left on an eleven-point scale, and more than a third (38 per cent) chose one of the two points furthest to the left. And 16 per cent chose the furthest possible point to the left on an eleven-point scale.

This means that there were almost as many people who chose the furthest possible point to the left as there were who chose all the conservative points, the centre-point and the most moderate left-of-centre point combined (16.6 per cent).

The members were also asked to rate themselves on nine specific political issues and mention who they voted for in the 2012 election, which also showed an overwhelmingly left-leaning attitude. I find the general political placement the most interesting, though, because it shows how these members think of themselves politically in the abstract.

People that freely self-identify as far-left in the abstract, in other words irrespective of specific political issues, seem to me to be signalling something: that they are committed to an ideology. The fact that such a large portion of the most influential people in academic social psychology do so suggests that this ideology is entrenched in their field.

And there are signs that point in that direction across the social sciences. Sociologist Carl Bankston paints a picture of a field that has institutionalised ‘social justice’ ideology on all levels over the past twenty years:

To attend a conference these days can feel like taking part in a rally of true believers. These associations are not government entities, one may argue, and they are entitled to become exclusive clubs of the committed. The problem is that the embedded ideologies of academic professional organizations are bound up with the embedded ideologies of universities. When we hire new faculty members or when we tenure or promote professors, one of the points we consider is whether the individuals concerned have been active in professional associations, especially the national association. Because the associations so strongly push political perspectives, universities implicitly encourage professors to hold and express the “correct” socio-political orientation.

From Bankston’s description, it seems clear that any non-leftist would find working in sociology almost unbearable. The research in the original paper suggests that the leftward shift in social science is likely due to a combination of self-selection, hostile climate, and discrimination.

In Haidt’s commentary, referring to the hostile climate, he includes part of an email from a former graduate student in a top 10 Ph.D. program, which he says is representative of several he received:

I can’t begin to tell you how difficult it was for me in graduate school because I am not a liberal Democrat. As one example, following Bush’s defeat of Kerry, one of my professors would email me every time a soldier’s death in Iraq made the headlines; he would call me out, publicly blaming me for not supporting Kerry in the election. I was a reasonably successful graduate student, but the political ecology became too uncomfortable for me. Instead of seeking the professorship that I once worked toward, I am now leaving academia for a job in industry.

With regard to discrimination, a recent article in Quillette presents a sobering anecdote from someone (who considers himself on the left) going through the process of applying to prestigious graduate programmes, and how he was consistently steered toward the expression of far-left ideological views by well-meaning advisors who presumably know what review committees are looking for. Here he summarises the process:

As a brief disclaimer, none of what I say here should be interpreted as a criticism of my advisors – not of their job performance and especially of their personal predilections. If anything, I think they did their jobs well. Given what I perceive as the entrenched far-Left political ideology in the world of academia, I’m confident that their advice improved my applications in the eyes of review committees. I can honestly say that by the end of the process, I felt as if the only way to be considered a serious candidate – by the Rhodes Trust, Harvard Admissions, etc – was to present myself and my proposed research as conforming entirely to a far-Left political narrative.

It seems likely to me that there are self-reinforcing mechanisms at work. As the ratio of liberals to conservatives increased, a tipping-point was reached where conservatives were actively excluded from the social sciences, and as they have disappeared the more radical liberals are now outnumbering the moderates to the point where they too are being gradually excluded. In other words, it appears that social science is undergoing a purity spiral towards an increasingly radical left-wing ideology. The anecdote above suggests just this.

I suspect there is some truth to Krugman’s hypothesis, and the Pew Research data that Krugman links to does suggest there is a large group of politically unaffiliated scientists. Unfortunately, the data doesn’t separate natural scientists and social scientists. This suggests that Abrams’s data understates the extent to which both liberal and moderates have disappeared from the social sciences and supports the idea of a purity spiral in these fields.

If there has been a build-up of moderates among natural scientists, it means—since the number of moderates has decreased sharply among professors as a whole—that even more moderates must have disappeared from the other areas of academia. (It’s likely that the humanities have followed a similar development to the social sciences; a recent Quillette article by a classicist suggests as much, at least within their field.)

This is a much more serious problem than the number of conservatives in the field. If the social sciences were full of people who were moderate or apolitical, it wouldn’t be that much of a problem. But the fact that a specific ideology has become so entrenched, and is increasingly becoming more and more so as others—even moderate leftists like the graduate programme applicant above—are gradually disappearing from the field, is highly disturbing.

So, what is this ideology?

In the paper, it is labelled the liberal progress narrative, articulated by sociologist Christian Smith:

Once upon a time, the vast majority of human persons suffered in societies and social institutions that were unjust, unhealthy, repressive, and oppressive. These traditional societies were reprehensible because of their deep-rooted inequality, exploitation, and irrational traditionalism. . . . But the noble human aspiration for autonomy, equality, and prosperity struggled mightily against the forces of misery and oppression, and eventually succeeded in establishing modern, liberal, democratic… welfare societies. While modern social conditions hold the potential to maximize the individual freedom and pleasure of all, there is much work to be done to dismantle the powerful vestiges of inequality, exploitation, and repression. This struggle for the good society in which individuals are equal and free to pursue their self-defined happiness is the one mission truly worth dedicating one’s life to achieving.

No doubt most social scientists would nod their heads to this. Unfortunately, it’s so simplistic, and so full of vague, emotionally charged words that it’s not very informative. To understand leftist ideology, we need it to be more specific. What actual things in the current world does it want to replace, and what specific things would it put in their place?

Haidt, appearing on author Sam Harris’s podcast, gave a somewhat more specific description when he described leftist ideology as the following (starting at 01:02:09, lightly edited for clarity):

So, I take part in a lot of discussions, I’m invited to all sorts of lefty meetings about a global society and… you know… the left usually wants global governance, they want more power vested in the U.N., I hear a lot of talk on the left about how countries and national borders are bad things, they’re arbitrary. So, the left tends to want more of a universal… I’m just thinking about the John Lennon song… this is what I always go back to, Imagine. Imagine there’s no religion, no countries, no private property, nothing to kill or die for, then it will all be peace and harmony. So that is sort of the far-leftist view of what the end state of social evolution could be.

This is more specific than Smith’s narrative, suggesting initiatives such as reducing national power and redistributing property. This, of course, is a much broader definition of fighting oppression than for example abolishing slavery.

One could argue that as slavery and feudalism have been eradicated, terms like oppression, exploitation, and inequality have increasingly become dysphemisms for power differences of any kind. In this view, the fact alone that one country, group, or person is wealthier or more influential than another is sufficient for the label oppressive.

This isn’t to say that everyone who subscribes to Smith’s liberal progress narrative agrees with Haidt’s extension. The point, rather, is that the liberal progress narrative is so vague and emotionally charged that it’s probably unclear even to most liberals themselves what these terms mean when referring to the specifics of the modern world.

(I should note that Haidt now considers himself a centrist rather than a liberal, so he’s not claiming to describe his own position.)

Why is it a problem that the liberal progress narrative is so vague, yet has come to dominate social science?

Well, the liberal progress narrative is not new. Nor is extrapolating it into the future. In fact, one of the most influential documents in recent history, The Communist Manifesto by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, does exactly this.

Their central argument is that human history is a succession of systems, each less oppressive than the previous, until it reaches its conclusion in communism, a system with no oppression because everyone is equal. Aside from the historical extrapolation, Marx and Engels use much of the same terminology as Smith. The words oppression and exploitation and their derivates feature prominently, and capitalism is referred to as slavery—notably similar to the dysphemism suggested above. Consider the following:

[The bourgeoisie] has resolved personal worth into exchange value, and in place of the numberless indefeasible chartered freedoms, has set up that single, unconscionable freedom—Free Trade. In one word, for exploitation, veiled by religious and political illusions, it has substituted naked, shameless, direct, brutal exploitation.

Take away the specifics in The Communist Manifesto, such as the definition of classes, and it becomes almost indistinguishable from Smith’s liberal progress narrative. Compare for example Smith’s last sentence with what Marx and Engels write at the end of Chapter II:

In place of the old bourgeois society, with its classes and class antagonisms, we shall have an association, in which the free development of each is the condition for the free development of all.

The Communist Manifesto, along with Marx’s later works, played a key role in energising and coalescing communist revolutionaries, and several societies throughout the twentieth century declared themselves in accord with Marx’s theory. The results, however, have been consistently disastrous.

Very few social scientists are communists, I imagine. But why? If most social scientists subscribe to Smith’s liberal progress narrative, and communism is (arguably) the logical conclusion of the liberal progress narrative, then shouldn’t they subscribe to communism as the ideal human society?

The answer for many, presumably, is that they don’t subscribe to communism because it produced disastrous results. But if the main lesson social science has learned from the failures of communism is that eliminating private property is a bad idea, then it has learned far too narrow a lesson.

What it should have done is asked itself this: if communism is the logical conclusion of the liberal progress narrative, and communism has consistently failed disastrously, what does this tell us about the liberal progress narrative—or as Haidt calls it, Universalism?

What’s interesting about Haidt’s alternative interpretation of the liberal progress narrative is that he mentions two elements central to the narrative—private property and nations. And what has happened to a large extent is that as the failures of communism have become increasingly apparent many on the left—including social scientists—have shifted their activism away from opposing private property and towards other aspects, for example globalism.

But how do we know a similarly disastrous thing is not going to happen with globalism as happened with communism? What if some form of national and ethnic affiliation is a deep-seated part of human nature, and that trying to forcefully suppress it will eventually lead to a disastrous counter-reaction? What if nations don’t create conflict, but alleviate it? What if a decentralised structure is the best way for human society to function?

What if the type of mass-scale immigration currently occurring in Europe, containing relatively large amounts of people with different nationalities, cultures, and religions, is going against some of the core features of human nature? Maybe it isn’t, but if it is, do we have to wait until after the fact to say ‘well, globalism doesn’t work’, as we did with communism? Surely there is a better way.

Let’s set aside the liberal progress narrative for a while and consider a different narrative. Let’s call it the scientific progress narrative:

Once upon a time, human beliefs and practices were crude, steeped in superstition, and tightly regulated by central authority. Consequently, humans were at the mercy of not only an unpredictable and punishing environment, but also of each other. But the human aspiration for truth and stability eventually prevailed, as humans piece by piece began to assemble a model of not only their environments, but of human nature itself. With this understanding came the blueprint for establishing a robust, dynamic society that could withstand environmental pressures while effectively regulating human interaction. Thus, societies learned to harness human potential by working with human nature, not against it. Again and again, theories that were believed unquestionably true were replaced by better ones, often after heavy resistance. There is much still to be understood, but it’s clear that the struggle for a good society must be led by an uncompromising search for truth, however uncomfortable it might seem at the time. Any society that forces humans to behave against their nature is bound to eventually fail, and only truth can prevent this from happening.

Now, it’s not clear that this narrative contradicts the liberal progress narrative. In fact, for most of the past few centuries, the two—or some variants of them—have been held to be two sides of the same coin. Maybe they are. But it’s not obvious that they are, so it’s important not to conflate them. They both describe the past reasonably well. But what about the future?

Well, they appear to be diverging. The most important cause of the divergence is the advances in cognitive science, evolutionary psychology, and neuroscience, which has led to a model of human nature that many leftists find unacceptable because they perceive it to threaten the liberal progress narrative. As Steven Pinker wrote in The Blank Slate fifteen years ago (Kindle, loc. 92):

The taboo on human nature has not just put blinkers on researchers but turned any discussion of it into a heresy that must be stamped out. Many writers are so desperate to discredit any suggestion of an innate human constitution that they have thrown logic and civility out the window. Elementary distinctions—”some” versus “all,” “probable” versus “always,” “is” versus “ought”—are eagerly flouted to paint human nature as an extremist doctrine and thereby steer readers away from it. The analysis of ideas is commonly replaced by political smears and personal attacks. This poisoning of the intellectual atmosphere has left us unequipped to analyze pressing issues about human nature just as new scientific discoveries are making them acute.

The second point of divergence is when scientists uncover negative effects of programmes attempting to implement the liberal progress narrative. Consider Carl Bankston:

[I]n 1976 the president of the American Sociological Association, Alfred McClung Lee, led a movement to expel prominent researcher James S. Coleman from the association because Coleman had dared to draw the ideologically unacceptable conclusion from research data that busing and other means of forcible school desegregation were actually exacerbating segregation by intensifying white flight. To the ASA’s credit, the expulsion effort failed, but only after many attacks on Coleman’s character and motivations.

Now consider both these points in relation to, for instance, globalism. If the suggestion that national, or ethnic affinity (or more broadly, tribalism) is deeply rooted in human nature is considered taboo, and likewise any attempt to describe cultural clashes and lack of assimilation in, for example, Europe is forcefully attacked, this can accumulate to become a significant blind spot.

Add to that the practice within the social sciences of using dysphemisms like xenophobia to refer to non-Universalist attitudes towards globalism, and you have a situation where the pursuit of truth is being hampered in the quest to support the liberal progress narrative, and where there appears to be a disturbing lack of learning from the disasters of communism.

It is important that people stand up for science, even when it clashes with the liberal progress narrative – or Universalism, as Haidt calls it. Yet, as non-leftists and increasingly also moderate leftists are being excluded from the social sciences, there appear to be less and less people willing to do so. The consequences could be grave.