Escaping Conformity

Conformity, broadly defined, is a tendency to act or think like members of a group. In psychology.

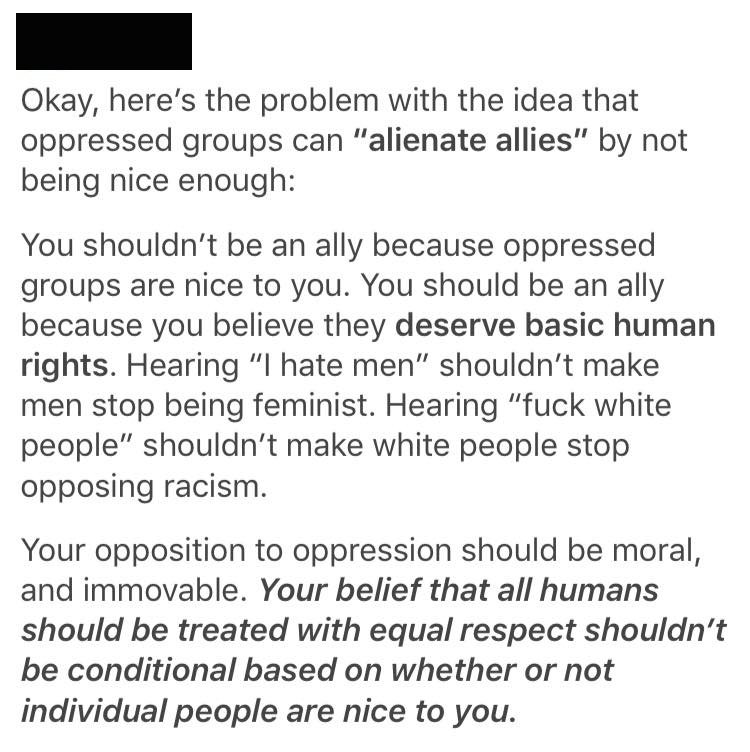

Recently, the following screenshot of a 2016 Tumblr post showed up in my social media feed, with a lot of responses in various states of violent agreement and disagreement gathering beneath it.

The person who reposted the screenshot also included their own message about not wanting “those” kinds of allies anyway, and adding for good measure that people who felt insulted by such sentiments should go fuck themselves. This isn’t a new kind of public attitude, particularly among identitarians. One doesn’t have to look too hard to find hundreds of additional examples of people demanding only the ‘right’ kind of allies for their cause.

My initial response to this post was not disagreement (although there’s the obvious vilification and over-simplification of people turned off by this kind of thing), but a familiar kind of frustration. Of course ugly rhetoric shouldn’t change whether or not I hold an ideological stance. Of course the behavior of some people who hold that ideological stance should not change my thoughts on its validity. Of course.

But, unfortunately, we simply do not live in that world. “Shouldn’t” is not the same as “won’t” or “doesn’t.” Human beings are regularly persuaded by behavior, rhetoric, and perception far more than they are persuaded by actual ideas, evidence, or arguments. And this isn’t just a “white, cis-gender male” thing; members of any and every identitarian group and sub-group will predictably be turned off by certain kinds of rhetoric and behavior.

Besides which, the author of the above quote is making an error in believing she understands her own movement. She has very little idea of who is on ‘her side’ and why. It’s not just identitarians who are making this mistake. We can see it in every kind of religious, political, and social culture. Publicly broadcasting this kind of ‘true believer’ miscalculation not only further estranges allies we don’t want, it also further alienates the allies we never had but assumed we did and loses countless allies we once had because we didn’t understand the people on our side in the first place.

Acknowledging this reality is essential to any person or group hoping to have a real cultural impact. This reality requires a reconfiguring of what we think about and how we speak about our “allies”. In other words, if we want to change the minds of those outside our group, we’d better get a firm grasp on who, exactly, is in our own group, and why they joined up or maintained their membership.

On Conformity

Conformity, broadly defined, is a tendency to act or think like members of a group. In psychology, however, conformity is defined as “the act of matching behaviors, attitudes, and beliefs to group norms.” Psychologists label the three main motivating factors for conforming to the views of others as compliance, identification, and internalization.

- Compliance is the kind of agreement offered in pursuit of social approval. ‘Virtue signaling’ is an example of this behavior that has recently gained some notoriety. In order to demonstrate to others that we are good people or the ‘right kind of people,’ we espouse certain views. This kind of conformity is rewarded with a kind of cultural cache. We do it to gain access to a tribe we want to join, to gain power we want to possess, or to defend ourselves from social harm.

- Identification is the kind of agreement that’s offered in pursuit of a kind of identity for oneself. So, for example, person X holds viewpoint Y. So, if I am motivated to be like person X, I may espouse viewpoint Y. We do this all the time, often conforming to the ideas of people we admire in our workplaces or ideal jobs. We often do this unconsciously, and we don’t necessarily do it for cultural acceptance. If I want to be, for example, an independent, powerful thinker, I might mimic the viewpoints of others I consider to be such thinkers, even when I haven’t given their opinions much thought. This is so I can tell myself a convincing story about who I am.

- Finally, internalization means you conform because you agree with the ideas of a person or group, and believe in them, too. In other words, you conform because you have been convinced by someone’s arguments and ideas. These arguments aren’t always rational or good; they just have to be convincing to you. In other words, internalization has no inherent good or bad value — it takes being convinced by thorough, rational, evidence-based arguments to turn internalization’s value toward the positive.

These three motivating factors are not mutually exclusive. They work together, and they change over time. For example, I may be primarily motivated towards a group because we share viewpoint X. But then, over time, I come to care more about staying within the group than I do about viewpoint X. Which means that, as the group shrinks and grows, and as its priorities and viewpoints and activities start to change, I may actually begin to engage in behavior Y, which is likely to frustrate my attempts to make viewpoint X a reality.

In other words, even if I am a ‘true believer’ and/or I conform for rational reasons, that is no protection against illogical and counter-productive behaviors on behalf of my ostensible cause.

Conforming for the Wrong Reasons

So what about conforming for apparently ‘irrational’ reasons such as compliance and identification? Perhaps surprisingly, conforming for these reasons isn’t necessarily correlated with positive or negative behaviors, either. Conforming for social approval or a sense of identity often means that a person will behave in the same way that their group is behaving. If most of a group is behaving inconsistently with their stated goals, then these faux-believers will follow. But, by extension, if a group is behaving in a productive way for the accomplishment of a goal, these same faux-believers will be infinitely valuable. Not just because they add raw numbers, but because they will take positive action for a cause, even if it’s one they joined for ‘irrational’ reasons.

So being a true believer in a cause doesn’t necessarily mean we’re any more effective in fighting for that cause. Often, it’s just the opposite. Our righteous indignation at outsiders’ disbelief can make us particularly bad at convincing those outsiders. And this self-righteousness is hypocritical, because we are all misguided faux-believers about countless ideas. We all sign onto ideologies with irrational or poorly-reasoned motives.

As human beings with limited capacity and attention, we cannot hope to enjoy limitless expertise and knowledge on every issue. So we choose what we pay attention to based on our priorities and interests. And we choose who and what to believe based on the types of people, systems, and behaviors we are drawn to. If I don’t know a lot about a particular topic, all that’s really guiding me to a certain viewpoint is a sufficiently convincing surface-argument, what I want others to think of me, and my sense of my identity. And how do I decide which group coincides with who I want to be or what I want others to think of me? By looking at group behaviors, group expectations, and the reactions of outsiders to that group. I look for those people to whom I’m already drawn and well-disposed.

For example, I don’t have anywhere near the knowledge necessary to prepare a thorough, scientific defense of climate change. What I do have, however, is a deep understanding of how science does (and sometimes doesn’t) work. I care deeply about this and try to stay knowledgeable about new pitfalls and problems in the system. I also know how scientists and thinkers I trust on other issues feel about the topic. So I feel safe conforming to the consensus viewpoint of these sources. And, because the stakes are high, I feel comfortable advocating strongly for the existence of climate change and the need to combat it.

I’m also drawn to people who, by default, treat others with respect, who value different ideas and who try to find some common ground. Those who debate and discuss instead of fight. I am drawn to people who believe different things from me, people with new or strange or crazy ideas. I want to hear them and consider them carefully.

What’s more, just as I am drawn toward trusting in the reality of climate change by my knowledge of science as an enterprise and by the views of specific scientists, I am pushed away from ideas based on my revulsion to specific or even “types” of people who hold other ideas or behave in other ways. These impressions of other people or groups don’t have to be accurate; they are just as often formed by the prominence of, or my proximity to, representatives I don’t like or trust. In other words, fear and loathing are just as powerful (and probably more powerful) than attraction and trust.

These cultural and identity-focused motivations are magnets, and they can repel as easily as they attract. The phrase, “I’m offended,” for example, is often just a culturally acceptable way to say “I’m emotionally repelled by that.” But that emotional pushback is selective and often misguided. It has very little to do with the truth or rationality of what is being said or done. And it ignores the fact that the truth, to unfamiliar ears, is very often ‘offensive.’ There are undoubtedly truths I am missing because I fear or loathe the conservative or progressive representatives of those truths who are the loudest or closest to me.

But, as disheartening as those facts are, there are even bigger hurdles to jump in order to accept new ideas. We also have to overcome the discomfort of confronting that we were wrong in the first place. In a 2010 paper, social workers Elizabeth Sullivan and Robert Johns forwarded the notion that,“[t]he impact of new learning is traumatic because it challenges previously held attitudes, feelings and knowledge, with which the person defines who they are, and results in feelings of loss of present self-concept prior to the formulation of a new self-concept which embraces the new attitudes and knowledge.”1

And so we are, yet again, mostly resistant to changing our views or beliefs due to our emotions, not our rationality.

What this means is that we are often swayed by things that should be tangential to any rational ideas or arguments at hand — things as potentially peripheral as credibility, likability, what our group thinks of an idea, what our identity ‘allows’ us to believe, and so on. The social psychologist Jonathan Haidt has said that “our minds are pattern matchers that make very quick judgments and then we use our reasoning afterwards to justify what we’ve just done.”

He compares our decision-making to a person riding an elephant; you can talk to the person — the logic/rationality — all you want, but if you don’t influence the behavior of the elephant – the gut/intuition – you’ll never ever persuade someone. As Abraham Lincoln observed:

[A]ssume to dictate to [a man’s] judgment, or to command his action, or to mark him as one to be shunned and despised, and he will retreat within himself, close all the avenues to his head and his heart; and though your cause be naked truth itself, transformed to the heaviest lance, harder than steel, and sharper than steel can be made, and though you throw it with more than Herculean force and precision, you shall be no more be able to pierce him, than to penetrate the hard shell of a tortoise with a rye straw.

So, to return to the example at the top of this essay, a person claiming that their group isn’t being treated humanely should probably consider that they will lose a great deal of credibility (and likability) by refusing to treat others humanely. This kind of public unkindness doesn’t just alienate members of the specific group you’re insulting, but anyone who cares about even a single member of the insulted group. It also alienates anyone who believes that treating other people humanely is important for its own sake (in other words, the very people who might otherwise have sympathy for the group’s arguments).

And when members of a group hurl such insults and start demanding ideological purity, it’s often a sign that they aren’t very confident in their ideology, or don’t even believe in the ideas they’re professing, or at least not as much as their desire to exclude out-group members. This is a recipe for stasis, and it is often the antithesis of what the group claims to be about. For example, as I mentioned in a previous article:

[O]nly around 20 percent of the American public refers to themselves as either a “strong feminist” or a “feminist” (YouGov Poll, Washington Post-Kaiser Family Foundation Poll). But when asked in these same polls if they believe that men and women should be social, political, and economic equals, the numbers flipped. Around 80% of the respondents answered in the affirmative, and only 9 percent said no.

This isn’t a problem for people who conform because of their compliance or identification with the feminist tribe — for self-definition or social-definition. It’s only a problem for those who really want men and women to be social, political, and economic equals and who think feminism is the best vehicle for accomplishing those things.

In other words, when people become puritanical, exclusionary, angry, and defensive, they probably aren’t true believers, either. They’ve probably got some other reason to cleave to their group and entrench a bitter status quo. After all, if things really changed as they say they want them to, their group would lose its reason to exist.

We find tribalism like this right across the societal and political spectrums. This is something about which we should all be more aware. We can’t allow ourselves to become so mesmerized by our identities or our warring tribes that we can’t accomplish the collective goals we say we believe in or recognize better ideas, even if they come from people or groups we don’t like.

How to Override Our Conformist Selves

Of course, we can’t simply stop being conformists, either. We are all members of a tribe, whether we announce it publicly or even acknowledge it to ourselves. And these tribes often have very little to do with ideas and more to do with reacting to another tribe’s very existence in proximity to our own. We are social animals, and we will continue to seek out groups that become a family to us. And these associations will corrupt our ability to think rationally if we’re not careful. Joining any group makes us resistant to other groups and ‘their’ evidence.

One reason for this group-based evidence resistance is the stories we tell ourselves about the world around us and its players. Michael Shermer has pointed out that these narratives can play a huge role in our ability to change minds. In other words, we tell each other (and ourselves) carefully constructed (often-false) stories about the villains and heroes in our society who we think embody the qualities we love or hate.

Religious people, for example, are nowhere near as stupid as many prominent atheists seem to think they are. And knowing the veracity of evolution is not a mark of any great intelligence, either. Conversely, atheists are nowhere near as arrogant as religious people think they are. There is plenty of arrogance in both groups to go around. Yet these are stories that get told a lot and are widely believed, not least because they flatter group members and disparage opponents.

And these powerful stories can make us resistant to good ideas that those groups may have. And the ugly stories we tell contribute to those other groups’ resistance to our ideas. Instead of engaging with each tribe’s actual ideas on any given point, these encounters often become an ever-escalating “rage-storm” over symbolic memes that each group has created about the other, and which have very little to do with the actual ideas or attitudes of either.

A recent study by Sam Harris, Jonas Kaplan, and Sarah Gimbel demonstrated just this point, by showing how heightened emotional states in the brain play a large role in evidence resistance. Finding a way to recognize when our emotions are overpowering our reasoning capabilities — and why they are doing so — is essential if we are to think more rationally.

Anna Salamon tells an illustrative parable about this type of emotional thinking. The little girl in the parable wants to be a writer, so she writes a story and shows it to her teacher:

“You misspelt the word ‘ocean’,” says the teacher.

“No I didn’t!” says the kid.

The teacher looks a bit apologetic, but persists: “‘Ocean’ is spelt with a ‘c’ rather than an ‘sh’; this makes sense, because the ‘e’ after the ‘c’ changes its sound…”

“No I didn’t!” interrupts the kid.

“Look,” says the teacher, “I get it that it hurts to notice mistakes. But that which can be destroyed by the truth should be! You did, in fact, misspell the word ‘ocean’.”

“I did not!” says the kid, whereupon she bursts into tears, and runs away and hides in the closet, repeating again and again: “I did not misspell the word! I can too be a writer!”

So, in this parable, the little girl is conflating a bunch of separate questions in her head: “Is ‘oshun’ spelt correctly?”; “Am I allowed to pursue writing as an ambition?”; “Will I ultimately succeed as a writer?”; etc. To the girl, the answers to all these questions will be the same. If the answer to the questions is yes, all is well with the universe. If it is no, then everything she wants and believes about herself and her world comes crashing down around her.

But we must learn to ask and answer such difficult questions separately. For example, “Do you believe in feminism’s stated goals” and “do you agree with [representative feminist]’s tactics/rhetoric?” do not necessarily have the same answers. Similarly, saying that you agree with feminism’s stated goal of equal gender status, rights, and opportunities does not mean you’ve somehow betrayed your declared tribe of rationalists, scientists, and independent thinkers. It does not mean you have signed on for rioting about college speakers or advocating genocide on social media or assaulting people who say or believe things you don’t like. And saying that you agree with a single point that an unpopular or controversial speaker has expressed does not mean that you agree with anything else he or she says or does.

I think that maybe, instead of simply trusting the ugliest narratives that our groups tell each other about other groups, we should do what the social media post at the beginning of this essay suggests; we should try to separate the ideas themselves from their actors. This separating isn’t something that will happen automatically for most of us; it’s something we have to will ourselves to do. It is hard, and as soon as we think we’ve done it properly regarding one idea, we have to start all over again with another. And again and again and again.

And perhaps this is why we should all make it just a little bit easier for those in other groups to see our groups’ best qualities. If we really believe in the importance of our given cause, then we should be hungry for almost any allies that will help us advocate for it. Even if they have some objectionable qualities. Even if they have some objections about our qualities. Even if they’re only a half-hearted conformist with some reservations. Like me. Like you.

Reference:

[1] Elizabeth Sullivan & Robert Johns (2010) Challenging values and inspiring attitude change: Creating an effective learning experience, Social Work Education,21:2, 217-231, DOI: 10.1080/02615470220126444