Education

The Evergreen Meltdown

Evergreen’s prognosis is guarded at best, but it might explain what ails higher education in general.

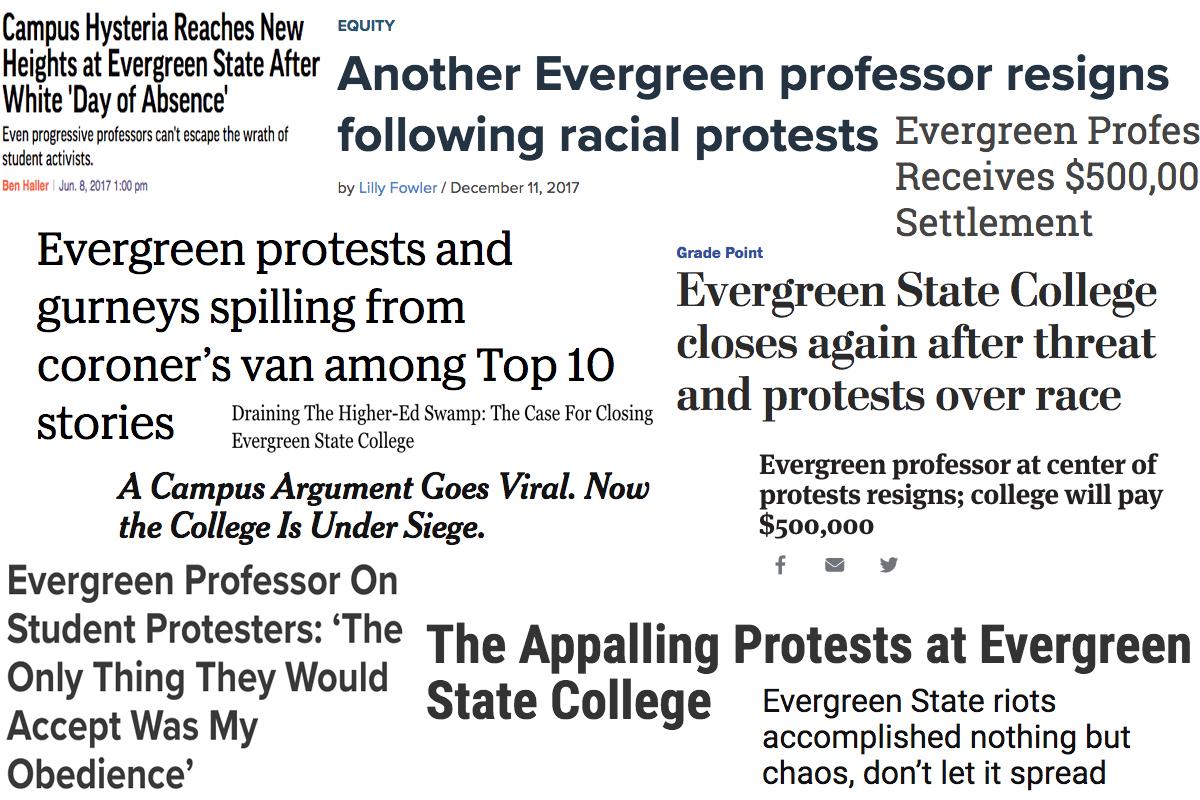

A case report will often describe a condition that is an extreme or unusual version of what one might typically observe. In medicine, it can be used to illustrate and explore disease mechanisms and the underlying pathology of more common manifestations of an illness. What has transpired and continues to transpire at The Evergreen State College where I teach provides some important lessons. My college is now famous for its intense student protests, the bizarre ousting of biology professor Bret Weinstein, and the absence of public support for Weinstein from faculty and a college president who thinks he might be a white supremacist. But these are only clinical symptoms of a much deeper disorder that had been growing at Evergreen for some time, and is only at its early stages in many universities across the country. Evergreen’s prognosis is guarded at best, but it might explain what ails higher education in general.

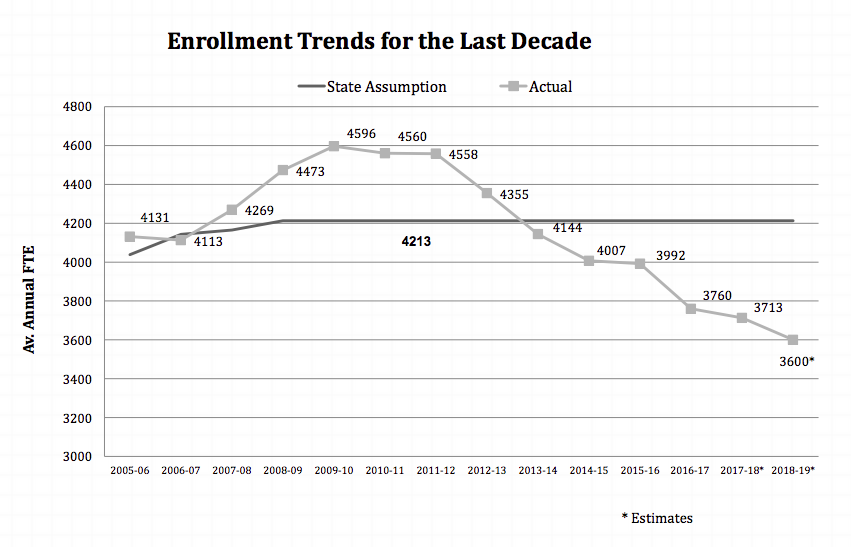

Earlier this month, in his annual State of the College address, President George Bridges announced that next year’s projected enrollment for Evergreen will be 3100 students. This represents a 19 percent drop from this year, and continues a steady downward trend that began in 2009. Next year, Evergreen (a public college) will likely be serving 26 percent fewer students than is currently funded by the state legislature, despite having a nearly 100 percent acceptance rate. In his address, Bridges speculated that an improved economy may have resulted in fewer people looking to earn college degrees. But that doesn’t explain the fact that all other four-year institutions in Washington State have seen increases in enrollment during the same time period that Evergreen saw its student population shrink by 33 percent. In an effort to rally dispirited faculty and staff, Bridges also suggested that the college’s enrollment decline and looming financial crisis could be due to a vicious social media attack by politically motivated outsiders.

I have a different hypothesis for Evergreen’s predicament. The college has become a hostile and intolerant environment for diverse viewpoints, and it is this that is causing students to leave Evergreen, or discouraging them from applying in the first place. When undergraduates become fearful of expressing unpopular opinions out of concern that their classmates, and sometimes even their faculty, will shun and verbally harass them, they are likely to seek a different college. Students might feel they are not getting a good return on their investment if they are forced to attend workshops promoting a particular socio-political agenda unrelated to their academic and career goals. When students are told in a seminar that they can or cannot speak based on whether they belong to a particular category of people (e.g., race, gender, ethnicity, sexual orientation), is it surprising they might feel discouraged and drop out? They will tell their parents, family, friends, and neighbors. A college’s reputation for honest intellectual inquiry can be tarnished remarkably quickly if it promotes a culture of self-censorship fueled by a constant fear of “offending” certain people.

Over a year ago, the social psychologist Jonathan Haidt warned against what might happen if a university’s main objective becomes social justice rather than the pursuit of truth and knowledge. Little did he know that it had already happened. In 2011, my college changed its official mission statement to read: “Evergreen supports and benefits from a local and global commitment to social justice.” The fundamental problem is this: how and in what form a “just society” should manifest itself is not a self-evident truth closed to debate and discussion. Words like “diversity,” “equity,” and “sustainable” have been stripped of meaning and are used to obscure real issues that demand exploration. If social justice is institutionalized in a manner that discourages foundational questions about vaguely defined terms, then a college cannot be inclusive or educational. In addition, Evergreen’s absence of multiple perspectives among faculty has created a campus culture that reinforces its own beliefs at the expense of all others.

President Bridges, college trustees, administration, and faculty believe that the answer to Evergreen’s current enrollment crisis is to double down on its specific brand of social and political activism as a primary selling point for prospective students. Perhaps this will prove to be a smart marketing strategy and Evergreen can fill a niche for undergraduates who are passionate and committed to fighting for the oppressed against those with privilege and power, without the stress of having their ideas challenged in the classroom.

But my deepest fear is that this approach to education will actually harm the very people it is intended to help. Shortly after becoming Evergreen’s president, Bridges accused the University of Chicago of being out of touch with the “academic and developmental needs of many students,” in an op-ed piece for the Seattle Times disagreeing with Dean of Students John Ellison. In an acceptance letter to Chicago’s class of 2020, Ellison wrote: “Our commitment to academic freedom means that we do not support so-called ‘trigger warnings,’ we do not cancel invited speakers because their topics might prove controversial, and we do not condone the creation of intellectual ‘safe spaces’ where individuals can retreat from ideas and perspectives at odds with their own.” In response, Bridges argued that the University of Chicago’s elite don’t need the kind of sheltering that Evergreen’s more vulnerable student population requires: “At The Evergreen State College, where I serve as president, 90 percent of our students belong to at least one group traditionally underserved by higher education: first-generation college students, low income, people of color, veterans, people with disabilities or students of nontraditional age.”

This notion that Evergreen students are somehow less capable simply because they belong to a particular segment of society is insulting as well as prejudicial. Shielding historically underserved groups of students from diverse viewpoints under the pretense of protecting them from emotional harm, will only increase inequities that exist across society by denying them the opportunity to develop the critical thinking skills necessary for social reform. Even worse is the bigoted assumption that a student’s race, gender, ethnicity, sexual orientation, age, or socioeconomic status automatically defines their values and opinions. Stereotyping Evergreen undergraduates based on group identity, while considering them unable to contemplate certain uncomfortable ideas may be bad for business. More importantly, it is also antithetical to what the educational mission of a college ought to be.

We mustn’t let student protests and debates about free speech on college campuses distract us from diagnosing the root causes of the sickness. In Evergreen’s case, it began with a severe lack of viewpoint diversity among faculty that became toxic when conjoined with a commitment to social advocacy and activism. Colleges that address these issues early will survive and even thrive while others like Evergreen will wither. And those marginalized students seeking justice for themselves and others will realize that they deserve a school where ideas can be exchanged freely.