Art and Culture

Nobody's Victim: An Interview with Samantha Geimer

The woman raped by Roman Polanski when she was thirteen reflects on her candid memoir, #MeToo, and the culture of victimhood.

On January 9th, I noticed the French journalist Anne-Elizabeth Moutet report on Facebook that the open letter she had co-signed protesting the excesses of the #MeToo movement had received endorsement from an unexpected source. Samantha Geimer was the girl raped by Roman Polanski when she was thirteen years old, and her experience is frequently cited by #MeToo activists and supporters as evidence of Hollywood’s moral turpitude and hypocrisy.

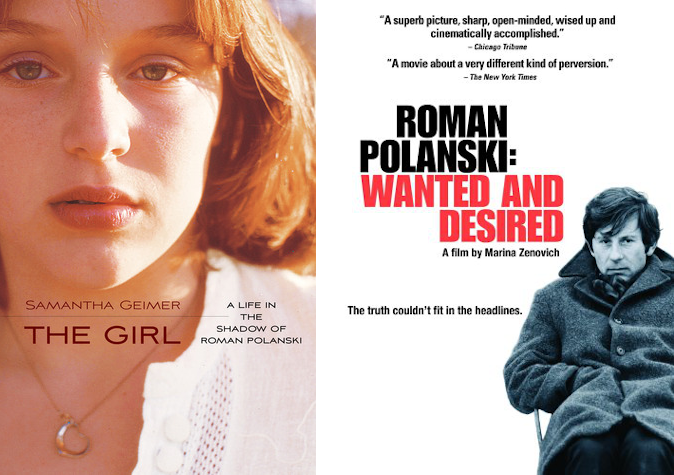

Browsing Geimer’s Twitter timeline, I discovered that she is also one of a minority of voices expressing scepticism about the resurrection of child abuse allegations made by the Farrow family against Woody Allen. Intrigued, I read Geimer’s memoir The Girl: Life in the Shadow of Roman Polanski. Her book is thoughtful, frank, refreshingly matter-of-fact, and offers a counter-narrative that sits uneasily with the use activists and journalists have routinely made of her story. I got in touch with Geimer through a mutual friend, and she kindly agreed to an interview with me to discuss her book, the Polanski case, #MeToo, Woody Allen, and the ongoing controversies surrounding all four.

The exchange below had already been completed when Hadley Freeman’s essay about the Polanski rape case appeared in the Guardian on Tuesday morning. Freeman concludes her article by reporting on her failure to secure disavowals of Polanski from celebrities who signed a 2009 petition in his support after he was arrested in Switzerland. Freeman makes no mention of Geimer’s memoir, nor does she include a comment from Geimer herself. This omission isn’t being noticed by those sharing the article on Twitter.

So I followed up with Geimer, and asked her what she made of Freeman’s essay. Those brief remarks are at the front of the interview. The rest of our exchange then proceeds sequentially and unamended. It is rather long, but I encourage those who enjoyed Hadley Freeman’s article to read this interview too. It offers an invaluable perspective on the events Freeman describes.

Quillette: On 30 January, the Guardian published a long article by Hadley Freeman about the Polanski case. Although your Grand Jury testimony is quoted, you are not. Did Freeman approach you for comment?

Samantha Geimer: No she did not.

Q: The article has been widely circulated and praised. After you tweeted a response to it, you and Freeman had quite a fraught Twitter exchange. Can you summarise your problems with her article?

SG: She cherry-picked facts to suit her own opinions and her depiction of my rape is a pornographic mischaracterization. A word on the testimony. I was a terrified 14-year-old [Geimer, then Gailey, turned fourteen a couple of weeks after the rape occurred] alone on the stand in front of more than twenty people. I was there to prove two things: that the sex had occurred and that I did not want it. I never told Polanski to “keep away” during the rape and I was not crying. If Freeman wanted an accurate account of what occurred offered outside of the pressurized environment of the legal proceedings, she could have picked up my book. But where is the sensation in that? Reports in which strangers talk about my anus are their own kind of violation. As for the latecomers, not one of them stood up for me in 1977. I owe them nothing today. I did not get justice, but they expect that I owe them something? No.

Q: Let’s begin by discussing your 2013 memoir, The Girl: Life in the Shadow of Roman Polanski. Until its publication, you had been reluctant to speak about the case even after your identity became public. Why did you finally decide to speak up?

SG: After my identity became widely known, I didn’t mind talking about it. But what I said never made a dent in the false narrative that already existed. It was very frustrating. After Polanski’s surprise arrest in 2009 and the mayhem that caused in my life, I wrote the book to put the truth of my experience (all 35 years of it) down on paper once and for all. I thought that instead of answering the same questions over and over again and hearing the same false ‘facts,’ my story would be there for anyone who wanted to know the truth. It turned out to be much more cathartic for myself and my mother than I expected so I am very glad I wrote it.

Q: One of the most striking things about your account of the rape, the legal proceedings, and the media frenzy that followed is your measured tone. This provides some room to think away from the feverish pitch of the media commentary. Did you make a conscious decision to adopt this approach?

SG: I think that may be part of my personality. But also it was a survival instinct to protect myself against all the wild allegations and what felt like hysteria around me. It is just the way I experience dealing with all of it: putting it into perspective and working out what was happening, sorting through it in my mind, and moving past it each day.

Q: The sections of the book that do betray impatience are those dealing with the uninformed judgments made by commentators. You hold those eager to defend Polanski and those eager to denounce him equally responsible: “It seemed the entire world was telling me I was either [Polanski’s] little slut or his pathetic victim. I was neither. Why did everyone want me to be one or the other?” What do you think accounts for this apparent aversion to complexity?

SG: I am not impressed by ill-informed bandwagon activism or journalists more interested in sensation than facts. When it is your life and people are telling lies about it, putting words in your mouth or re-dramatizing a tendentious version of events from which they can benefit, it is maddening. I know what happened, and I know how I feel. I will not silently let my life be distorted and used by strangers, whatever their intention, knowing full well that they care nothing for me. The use of a victim or the accused as fodder for profit or prurience by those who have the nerve to pretend they are doing a public service is hypocritical and immoral.

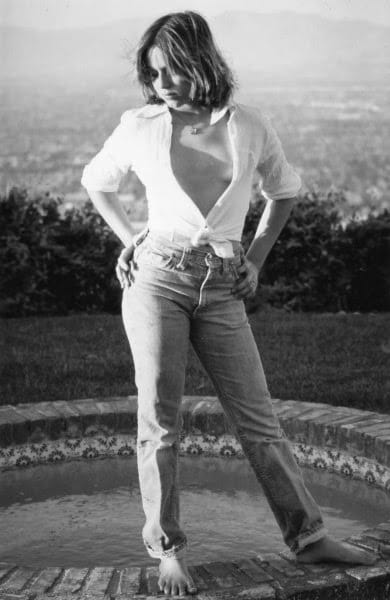

Q: It wasn’t until I saw Marina Zenovich’s HBO documentary Roman Polanski: Wanted and Desired in 2008 that I realised how little about the case I knew. What’s remarkable is that, in a film dealing with a hugely contentious trial, the testimony of all the surviving participants converges on a single coherent version of events. You and your lawyer Larry Silver participated in the film as interviewees. Were you pleased with the result?

SG: We were very pleased that we participated in Marina’s film. She did an astounding job of bringing clarity to such a complicated series of events. It went a long way to bringing my mother some closure, for which I am very grateful. From the inside looking out it was as if we could not explain what actually happened; we could only tell people that what they thought had happened was wrong. Marina brought order and historical context to a traumatic event which we were unable to bring on our own.

Q: Towards the end of the film, prosecuting assistant District Attorney Roger Gunson admits to understanding why Polanski finally despaired of the legal circus and fled the country. Do you share this feeling or, in view of everything that’s followed, do you wish Polanski had bitten the bullet and allowed the case to be brought to a conclusion?

SG: I share Roger Gunson’s feelings. By the end of the trial, [presiding] Judge [Laurence J.] Rittenband seemed completely unhinged and certainly had no concern for me. He wanted me on the stand to aggravate media interest, and when he couldn’t get that, he started to take it out on the defendant. The judicial process broke down entirely and there was no way to trust him or to know what he might do next. [Rittenband was later removed from the case.] I was relieved when Roman left and the court had no way to torment me anymore. What most people don’t know is that I was also put on a plane and sent out of state to hinder Rittenband’s plans to see me testify in the “trial of the century.” Roman and I deserve a fair justice system as much and anyone else does. 41 years later, we are still denied it because each new DA and every Judge wants something for themselves.

Q: With reference to Jeffrey Toobin’s lengthy essay for the New Yorker about the case, you describe Polanski’s celebrity as a “double-edged sword.” Do you think celebrity hurt or helped Polanski on balance? And what complicating effect has it had on your own pursuit of justice?

SG: In our particular case Roman’s celebrity hurt us both. What little benefit it may have had was entirely eclipsed by the damage those desiring a little piece of it for themselves did to both of us and the case. The only exceptions seemed to be [prosecuting assistant District Attorney] Roger Gunson, and of course my attorney Lawrence Silver, both of whom my mother and I consider to be heroes.

Q: One of the threads running through the book is your powerful allergy to self-pity. Early in the book you write, “I made a decision: I wasn’t going to be a victim of anyone or for anyone. Not Roman, not the state of California, not the media. I wasn’t going to be defined by what is said about me or expected from me.” Towards the end, you write, “I was the victim of a crime—I am, and always will be, a rape victim. But I’m not a victim as a person.” That final distinction strikes me as quite subtle but astute. What is it about victimhood that caused you to reject its temptations so decisively aged just thirteen?

SG: I turned 14 that month, but I don’t think it was really my age. It was just who I had been raised to be and—I’d like to think—where I was raised, in York, PA. I was not taught to be fearful and ashamed or to cower before authority without question. I was not taught that sex is damaging or that it would diminish me. I understood that far worse things happen to people all the time. I was taught to be strong and confident, to be a survivor and to realize that those who would victimize me were the ones who were weak. Bad things happen in life. We must deal with what comes our way and not just roll over and die. People call this “victim blaming,” but I call it good advice and something to strive for even when you think you can’t. In his song “Refugee,” Tom Petty sings: “Somewhere, somehow, somebody must have kicked you around some/Tell me why you want to lay there, revel in your abandon.” Wise words.

Q: In early January, the science writer Rolf Degen tweeted a 2004 paper by George Bonnano [above] arguing that human resilience is much more common than we think and that we routinely underestimate our capacity to recover from bereavement and trauma. In your book you write that recovery and resilience were implicitly discouraged: “Almost immediately, from the start of this case, I felt the pressure to be damaged.” Your refusal to behave in the manner expected of a traumatised victim has provoked particular anger from some of those who claim to speak for victims of sexual assault. The Oprah Winfrey Network’s Dr. Phil has diagnosed you with “victim’s guilt” and you recently wrote that you’ve been called a Stockholm Syndrome sufferer and even a rape apologist. What do you think explains this kind of hostility and condescension from those ostensibly dedicated to supporting people like you?

SG: It’s extremely frustrating. Why do strangers want to project their own dysfunction onto others? When I told my mother I was okay she never questioned it. My family accepted that easily, but that did not absolve Polanski. My mother showed me that I did not have to accept being used that way and it was worth a struggle to prove that, no matter what the cost to our family. So why do others insist I must suffer, and that if I do not display the correct amount of agony and shame, that there must be something wrong with me? I don’t have to be injured to prove what Roman did was wrong. His intent was certainly not to injure or frighten me. People don’t like facts that don’t fit with their preconceptions. When you see how ugly and spiteful some of these people have been to me it shows that they really don’t care about my welfare at all. So then what is the point?

Q: “Polanski’s intent was certainly not to injure or frighten me.” You make a similar point in your book: “As wrong as he was to do what he did, I know beyond a doubt that he didn’t look at me as one of his victims. Not everyone will understand this, but I never thought he wanted to hurt me; he wanted me to enjoy it. He was arrogant and horny. But I feel certain he was not looking to take pleasure in my pain.” This consideration of motives and intentions is something I rarely see mentioned in public discussions of this kind of crime. In your own case, why do you think it matters?

SG: I think intention is relevant to understanding any situation. It is part of the whole picture and should not be dismissed without consideration. In my particular case, I understood rape to be when someone intended you harm, was mean to you, wanted to hurt or humiliate you or disregarded your feelings. It was clear to me that Polanski wanted to have sex and he wanted me to participate willingly and to enjoy it. That may not matter to some people, but it certainly mattered to me. I knew what was happening was somehow wrong, but he was not rough or demanding or cruel. I was thirteen years old. I said “no.” That makes it rape. I do not see the value in exaggerating the experience to prove that.

Q: Reading your book, it occurred to me that there’s an odd paradox involved in a lot of sexual assault activism. Emphasising the trauma and shame inflicted by rape helps to incentivise swingeing punishments and reinforce the taboo associated with sex crimes. But this has had the unintended effect of disincentivising resilience, and creating a perverse interest in encouraging victims to feel ashamed and traumatised. If some rape victims recover and thrive, activists might worry that rape will no longer be regarded as such a terrible crime. Is there a way to understand and talk about rape and sexual assault that avoids this trap?

SG: We need to eliminate the type of “activism” that requires damaged victims to operate. A kind of activism that glamourises pain and shuns recovery and strength offers no positive way to recover and move forward. When people are not encouraged to recover and are treated as if only expressing your pain and suffering to the world will help others, they ought to know that they are being fed a lie. It is absurd to require women to maintain permanent damage of some sort in order to convince themselves or others that rape is wrong. Rape is wrong. The only person to blame is the one who commits the crime, period. But it is the only crime in which victims are discouraged from being okay. If you are beaten up or your house gets robbed, that can also be traumatic, but at least no-one says you must never get over this or you will insult other victims. I think it is sexist and a way of reinforcing negative sexual stereotypes about women and sex.

Q: Polanski’s name is now being mentioned in connection with the #MeToo movement, usually by the movement’s supporters. But his name also cropped up in the controversial open letter signed by 100 French women criticizing the campaign. Reactions to the letter have generally split between those who understood what the letter was getting at even if they didn’t agree with every dot and comma, and those who found it outrageous and incomprehensible. On Twitter, you gave the letter your unequivocal endorsement. What was it about the letter that struck a chord with you?

SG: I was a co-signatory to the open letter. I was asked to explain why I had endorsed it and I posted an article on my blog explaining my reasons. Anyone interested can find it here.

Q: What do you think about the way the #MeToo movement has developed?

SG: I don’t believe the use of #MeToo as weapon is a positive development. I am disappointed to see it used to attack people instead of being used to bring people together in solidarity. If it is going to end up being used as a means to shame celebrities and politicians we dislike, we will be doing a disservice to all those women who suffer in the shadows. I am happy to see #TimesUp emerge, which seeks to change the world moving forward, which demands equality for women, and which does not try to glamourise weakness and victimhood. I want the freedoms my mother fought for: economic, sexual, reproductive, all of it. We do not need to be protected from ourselves. It is our survival of the past we should glamourise, not the pain it has caused.

Q: A recurrent and growing criticism of the #MeToo movement has been its more strident advocates’ reluctance to acknowledge the messiness of many human sexual interactions. The recent Aziz Ansari controversy divided the movement’s supporters over the difference between persistence and coercion and how we should understand consent and personal responsibility. The account you give of your own rape in the book is quite searching on this point. You were only thirteen and Polanski knew this. Nevertheless, you insist on taking responsibility for your own choices. Why do you think this is important?

SG: The Aziz Ansari story concerned an anonymous, one sided account of what an adult felt had been gross or inappropriate sexual behaviour by a celebrity. To name that celebrity but not yourself is cowardly, and the journalist who wrote it is an opportunist. Why are women so astute at judging when a man has used them sexually, but apparently oblivious to how those in the media use them that is, in its own way, just as wrong?

To your other point, responsibility is not the same as blame. I will be responsible for my own actions. To insist that I cannot be is a way of diminishing me. I will not be told that my actions—good or bad—cannot be attributed to me. It is a way of reducing women to something less than men. It is sexist, it is dangerous, and I think we should fight those who tell women they have no agency or power. There are those who would take back every right and liberty we have won by arguing that ladies can’t be expected to handle the world. To accept that your actions are caused by others around you is to accept that you are powerless and I won’t do that. I was thirteen, and what Roman Polanski did to me was a crime. Should I have told my mother about the topless photos [during the first photo shoot]? Yes. Would it have prevented the subsequent crime? Also yes. I don’t feel guilt about making mistakes, but to insist that I am incapable of comprehending them or learning from them is insulting.

Q: The section of the French open letter mentioning Polanski says, “Cinémathèque Française is told not to hold a Roman Polanski retrospective and another for Jean-Claude Brisseau is blocked.” On 25 January, the Washington Post’s theatre critic Peter Marks reported on Twitter that Godspeed Musicals had cancelled Woody Allen’s Bullets Over Broadway musical “in light of the current dialogue on sexual harassment and misconduct.” How—if at all—do you think moral judgments about artists should affect our ability to exhibit, appreciate, and enjoy their work?

SG: Moral judgments are personal. Everyone is free to not attend, purchase, or view anything at all depending on their own feelings. But I object when someone demands that I adhere to their moral views, and that if I do not I am somehow complicit. I do not need others to tell me what to feel or believe. This is puritanism and censorship dressed as empowerment. Why would I have an opinion of what others think of Roman Polanski’s work? Love it or hate it, it makes no difference in my life. If he never made another film, it wouldn’t undo what happened. I don’t want revenge or to see his career destroyed. How would that help me? I object every time I am used to protest Roman. But victims don’t matter—not forty years ago, and not now. It’s easier to hate certain celebrities and boycott their work as punishment for real or false indiscretions that occurred years ago than it is to help someone now, in your city, or on your block, who really needs it. It’s lazy if you ask me.

Q: In your book you say this about Polanski’s 2003 Academy Award for Best Director: “I never thought Roman would win, and I was quietly thrilled for his victory. It felt like a little strike against political correctness.” Even allowing for the various ways in which you have been let down by a dysfunctional justice system, this will strike many observers as a surprising remark. Can you explain your reaction?

SG: Roman and I have been thwarted at every attempt to put this behind us. I felt as if neither of us could ever catch a break. So I assumed that he would certainly not win, that political correctness or spite would be more important than the value of his work (I have never seen the movie). I resented the calls asking me what I thought of his nomination and demanding to know whether or not he should he be “allowed” to win. At the time, I wrote an op-ed for the LA Times arguing that it was ridiculous to conflate his work and profession with what happened decades ago. The Oscars are supposed to reward great art and entertainment, not congeniality. So when he won I felt like it was a big fuck you to everyone who insisted we must remain victim and monster for eternity. It felt liberating somehow. Our struggle for justice has left us allies for longer than we were ever adversaries so a win for one feels like a victory for both.

Q: In 1993, two separate investigations into the allegations of child abuse made against Woody Allen by Mia Farrow and her then-seven-year-old daughter found no case to answer. What do you make of the resurrection of these claims now and of the actors currently disavowing their work with him?

SG: If you choose not to pursue a case, if you cannot prove your allegations, then deciding to try your case in the court of public opinion decades later is a cop out. Dylan Farrow is not alone in her circumstances. But we have a justice system and the rule of law in our country and that is more important than one person’s desire to be “believed” or to exact revenge. What kind of example is that for those who have made peace with their decisions and experiences? That you must have the belief of strangers to heal? That you can never be whole if the person you believe to have wronged you is not punished? It’s simply not true. Most of the time, people can find the strength to recover and move on with their lives. How is it healthy to leave your emotional well-being in the hands of others, or to insist on their belief and attack those who decline? It’s a kind of emotional blackmail. Dylan did nothing wrong, but now she will be judge and jury, blaming others for her pain. I’m afraid I don’t like it.

Q: Mia Farrow has consistently defended Polanski since 1977 and until very recently spoke of him fondly. On 7 January of this year, amid the #MeToo controversy, she sent you a tweet apologising. You replied that no apology was necessary. Can you elaborate on why you responded as you did?

SG: Many highly respected celebrities wrote letters to the probation department on Roman’s behalf. They were his friends. Perhaps they didn’t believe that he could do such a thing. Who does not support their friends? They may have been a little hard for me to read, but why would I internalise those letters as an attack on me? I didn’t need their belief or support because I knew what happened. Letters and opinions don’t change that, and nor do celebrity endorsements. The hypocrisy of Dylan’s question “What if it had been your child?” came much later [in 2014]. After all, I am someone’s daughter. Mia’s public apology was offered as a reply to a random twitter post, and arrived on the day of the Golden Globes. I didn’t need it and I don’t want it. I felt used by someone pursuing their own vendetta against Woody Allen. After forty years Mia Farrow has now turned on her friend Roman, who I forgave decades ago. I’ll leave people to make of that what they will.

Q: The final line of your memoir reads: “Forgiveness is not a sign of weakness. It’s a sign of strength.” You have expressed your wish that Polanski be allowed to return to America so that you can both move on. Some of your critics, including the feminist writer and activist Jaclyn Friedman, have countered that rape victims do not have the right to forgive their attackers on behalf of society and that Polanski should be jailed whether you like it or not. How do you respond to this argument?

SG: Forgiveness is a strength that helps the victim. It frees you from hatred and regret. If I do not have a right to forgive “for the public” then victims do not have a right to make victim impact statements to the court and ask for punishment. You can’t have it both ways and only respect the views of those victims who say what you wish to hear. As I’ve already mentioned, people become angry when they discover they can’t use me to suit their purpose. Roman returned to the US, he served his sentence, and he was treated unjustly by a corrupt judge. It’s been forty years. Enough.

Q: Finally, do you think Polanski will ever be allowed to return to the United States? Or are all parties to the case now resigned to its insolubility, particularly in the current climate?

SG: No. When there is no benefit to doing the right thing, good luck finding a Judge or DA in Los Angles that will do their job. It’s all politics. We are not human beings in the eyes of the court, just a witness and a defendant measured by our value to the careers of others.

Samantha Geimer has lived in Hawaii for most of the past 30 years. She is the married mother of 3 adult sons, and grandmother to a 2-year-old girl. Now a part-time author, victims’ advocate since 2013, and feminist. You can follow her on Twitter @sjgeimer.