Centrism Debate

Universalism Not Centrism

Ideologies are like organisms, and tracing their origins back to common ancestors starts with a system of classification based on careful observation and comparison.

The notion of “centrism” aims to stake out ideological ground between the extremes of contemporary left and right. But the centrism-extremism distinction fails to get at essential differences. Finding those means going deeper into Western intellectual history.

Ideologies are like organisms, and tracing their origins back to common ancestors starts with a system of classification based on careful observation and comparison. Our goal is ultimately to unravel the DNA of ideological movements. However before DNA, you need Darwin and Linnaeus.

So let’s start with some actual specimens of “centrism.” Here I mean ‘neo-Enlightenment’ thinkers like Sam Harris, Steven Pinker, George Will, Maajid Nawaz, Scott Alexander, Christina Hoff Sommers, Christopher Hitchens, Bret Stephens. And their ideas have a clear line of descent from core Enlightenment values, which are under attack from factions on the left and right today.

Anti-Enlightenment ideas are springing up from the left in: attempts to shut down speech in the academy, increasing toleration of violence in “anti-fascist” and “anti-racist” protests, and rhetorical strategies aimed at opponents’ racial or sexual attributes rather than the content of their ideas.

Likewise, from the right: economic protectionism, scapegoating of foreigners, conspiracy theories, and explicit neo-Nazism.

What’s wrong with the centrism-extremism lens on these three camps (e.g., as ably outlined here)? Centrism is said to be a “consistent philosophical system” based on the idea that “progress is best achieved by caution, temperance, and compromise, not extremism, radicalism, or violence.” Centrism is for constitutionalism over identity politics and absolutism. And it eschews “grand theories” whether of the altruistic-authoritarian or extreme-libertarian variety, in favor of a more “pragmatic” issue-by-issue analysis, rooted in science and evidence.

How are any of these propositions justified by a core principle of moderation? There is no fundamental account of what moderation means here. There is just a vague sense that whatever the mainstream views of our culture happen to be, centrism is somewhere around there, sufficiently far away from what crazy people with crude posters or frog memes think. But why our culture? Indeed, why the particular sub-culture of smart cosmopolitans rather than that of fly-over radio stations or intersectional poetry jams?

The American founders were in fact radicals not moderates — just ask George III. Of course so was Mao. The point is that we need a clear ideological criterion for distinguishing good revolutions from bad ones, which centrism fails to provide. Or good absolutisms (like free speech) from bad ones (like papal infallibility or the dogma that the sexes are psychologically indistinguishable).

Also, about the idea of defining a philosophical system on the simple, pragmatic basis of science and evidence, because that’s what works, not grand theories — it’s already been tried. Indeed it was called “pragmatism,” and it crashed at the epistemological dead-end of denying the very concept of “truth” (insofar as “truth” refers to mental objects having some kind of correspondence with external reality). Pragmatism is what produced Richard Rorty. But let us turn back down that road in a bit.

If centrism-extremism doesn’t provide a good taxonomy, how do we find one? Biology gives us a model. Richard Dawkins’ famous insight here is to think of ideas — “memes” as he coined the term, in its broader sense — as the genetic units of our constantly evolving belief systems, mutating and replicating like genes do.

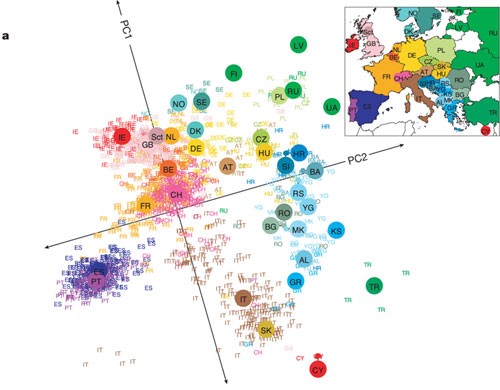

Once biologists identified the biochemical mechanism of inheritance and mutation through DNA, a whole world of analysis opened up. They could sequence (partial) genomes from thousands of subjects and then perform detailed, quantitative studies on genetic similarities and differences using the mathematical technique of Principal Components Analysis (PCA). An example of the results of applying PCA in a study of 3000 European subjects is shown below. It identifies two main axes (PC’s) of genetic variation among these subjects, which allows you to visually depict them all on a two-dimensional map.

What’s amazing is how closely this map, generated purely by looking at people’s genes not their addresses, corresponds to the actual map of Europe. Your genes alone are giving up the deep truths about where your ancestors were from in the world.

Sequencing genetic codes is a rigorous, scientific process. How does one sequence a memetic code? We are in the position here of biologists before the structure of DNA had been elucidated. They knew some such heredity mechanism had to exist, but they couldn’t yet measure it quantitatively in individuals.

Sequencing the Memome

While genetic codes are just linear streams of information, memetic codes have a complex hierarchical structure and are more dynamic in mutation. This will prove critical.

Essentially all heritable genetic mutation occurs in a single shot at the moment that sperm meets egg. Your genetic code is basically fixed after that point, through the rest of your life. Your memetic code, however, is constantly changing over your life, because you are constantly analyzing and updating your own ideas in intricate non-linear ways. (This essay, like any other, is trying to make you do just that!)

In other words, the key difference between biological and cultural evolution is the power of human reason as a means of reshaping the complex structure of people’s ideas in real-time. This is what explains the vastly higher rate of cultural vs. biological evolution. And here we have a big clue about which ideas are most important for cultural evolution: ideas that regulate the operation of reason itself — ideas about ideas as such.

The hard left has embedded within it certain deep views about reason. So does the hard right. And so does the nascent neo-Enlightenment movement. How do they all differ?

On the left we see the rise of micro-aggression and triggering theories founded on the idea that language is a game not a quest for truth. So if your team plays mean don’t try to justify it by saying your game is “true.” Campus speech codes: needed to rebalance power relations, which is what matters — not “truth” as filtered through your white consciousness. Oh now you are being oppressed by leftist authoritarianism, which violates your Enlightenment values? Stop logic-splaining to us! That’s just a meta-narrative you have constructed to deflect what we’re trying to tell you. Listen! Stop gesturing! So what if we roughed up that racist speaker while he was trying to escape our mob? He was here spewing white supremacist eugenics from his book on rural, white drug addicts and their dangerous cognitive deficits. “Free speech”!? Thomas Jefferson raped his slaves!

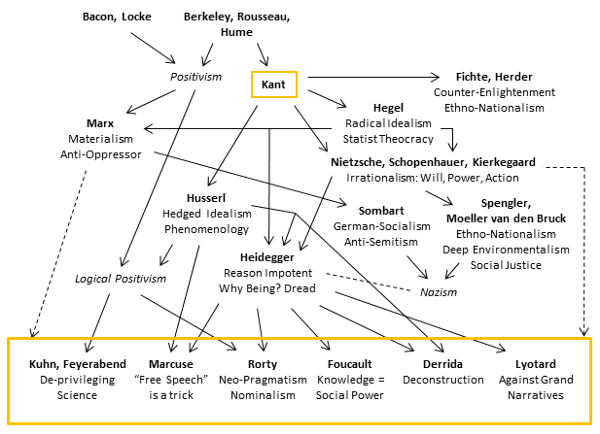

These slogans and intellectual norms did not spring spontaneously from the minds of twenty year-old college students. There is a clear and by now well known link between their professors’ ideas and the mid-20th century philosophical movement of postmodernism. Some key figures and theses:

- Michel Foucault reduces what the West had regarded as rationally derived knowledge to a means of power over the oppressed.

- Jacques Derrida gives us the deconstructionist language game, in which no objective meaning need be sought in a text. It’s all oppressor-speak.

- Jean-Francois Lyotard tells us to discard Enlightenment “meta-narratives” about human progress, which are just masks for the exercise of power.

- Thomas Kuhn turns the long arc of scientific progress into a geeky popularity contest. Paul Feyerabend adds that, epistemically, it might just as well have been a contentious game of D&D.

- Herbert Marcuse edifies us that ideas like “free speech” are merely a ruse performed by rich oppressors to trick the working class into subservience.

Perhaps the best single, compact resource here is Stephen Hicks’ Explaining Postmodernism. The present account is patterned on his essentialized dive into the deep origins of postmodernist ideas.

So where did these ideas come from? That perpetual focus on the oppressed goes back to Marx. And postmodernists were almost all committed socialists left holding the bag as the Soviet Union began to be exposed in the 1950’s. Their relativism was a convenient way out of this predicament.

But nearly the whole postmodernist brood was fathered by one early 20th century German philosopher. Martin Heidegger viewed man as wracked by the impotence of reason to deal with deep paradoxes like: Why does the universe itself exist? Why not just nothingness? Since reason cannot even comprehend such questions, our only recourse is to accept feelings of fear, guilt, dread as our natural state in the face of inscrutable Being.

Heidegger was reacting to his teacher Edmund Husserl and the phenomenological tradition. Phenomenology had sheepishly avoided metaphysical questions by studying only the pure actions of consciousness, not worrying about their relation to some hypothesized external world.

Another important influence on Heidegger and the postmodernists was, unsurprisingly, the explicit irrationalism of Nietzsche, Schopenhauer, and Kierkegaard. They shared the phenomenological premise that there is no objective way to connect rational thought with external objects. But they sought a supposed deeper access to reality via pure acts of will — i.e., via feelings, not reason.

And here we arrive at some common ancestors of the contemporary left and right. The alt-right, gaining steam today, is a younger movement, with more volatile foundations. But one central idea here is a racialist power-struggle metaphysics of the sort prominent in early 20th century German-socialist thinkers who cast Aryans into the Marxian role of the oppressed. Heidegger himself was notoriously sympathetic to National Socialism (Nazism). And one can trace other lines of influence from Nazism back to thinkers like Spengler and Moeller van den Bruck, who were themselves products of Nietzsche and the other irrationalists.

Tracing back even further leads to Georg Hegel, who influenced both Marx and the irrationalists. Hegel’s metaphysical idealism dealt with the objectivity problem (the severed link between mental representations and external reality) by simply denying that such a mind-independent reality even exists. Problem solved!

Looking over all these strands of thought, the objectivity problem stands out as a shared premise underlying all the factions — from Hegel to Heidegger and beyond. One can observe the objectivity problem already starting to surface mid-Enlightenment with George Berkeley and David Hume. But their main influence was just to raise questions. The hands shaping the West’s ultimate answers, according to Hicks, were those of Immanuel Kant. I have illustrated this grand narrative in the below diagram.

Kant’s critical innovation was the idea that rational consciousness is by nature distortive — cut off from “things-in-themselves,” the true, undistorted objects of reality that constitute a separate “noumenal” realm. Man can only access the “phenomenal” realm in which he, as a mortal being, is incapable of distinguishing between what comes from the true nature of things and what comes from the distortive lens of his reason. Kant explicitly named the motivation for his system: to save the innocent claims of religion from Enlightenment predators. Nevertheless, he formulated it as a secular, logical critique of reason from within, aimed to subvert the predators by their own claws.

There is scholarly disagreement about characterizing Kant as a fundamentally anti-rational force. What’s important here is not an evaluation of Kant’s thought in its entirety, but the inner logic of his key philosophical innovation (reason-as-distortive) and its explosive replication over the 19th century.

This punctuated the Enlightenment equilibrium that existed prior to Kant. Surrounding ideas needed to be adapted, and different adaptive schemes emerged: idealism, phenomenology, irrationalism. As we have seen, these all spawned their own intellectual lineages that later incestualized into postmodernism.

Principal Components of the Mind

Consider the above as our sequenced memome data. Now it’s time for PCA. Hicks gives us a lead by defining five essential aspects of reason — principal components, if you will:

- Objectivity: reason is not inherently distortive

- Competence: it is capable of comprehending reality

- Autonomy: it’s not subordinate to other means of knowing

- Universality: it applies to all areas of inquiry and all inquirers

- Individuality: it is an attribute of a single mind, not a tribe

To which let’s add:

- Emergence: it can be coordinated between minds without a central plan

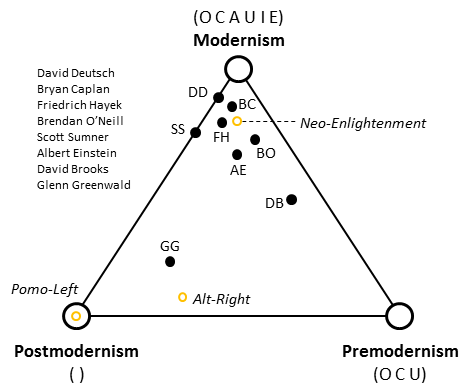

(This is meant in the broad Hayekian sense of spontaneous orders arising under certain systems of economic and/or memetic exchange). Hicks also splits post-ancient Western history into three major intellectual eras: the premodern, modern, and postmodern — roughly corresponding to the Middle Ages, Enlightenment, and recent continental scene. I would isolate the aspects of reason strongly affirmed in each era as follows:

- Premodern: (O C U)

- Modern: (O C A U I E)

- Postmodern: ( )

Indeed any particular ideology, of man or movement, may be broken down according to our six PC’s and then compared to these three clusters. Observe that this fine-grained picture does have not have any place for a centrism-extremism axis. (Mathematically, such an axis can be understood as lying roughly perpendicular to the plane defined by our three cluster points —i.e., centrism-extremism is just not informative in describing ideological variation over these eras.)

Here’s how I break down three movements of present-day interest:

- Pomo-Left: Purely postmodern

- Neo-Enlightenment: Mostly modern, but weaker (E) due to origins on the center-left

- Alt-Right: Strongly postmodern (with white men cast in the role of the oppressed) but with certain smaller premodern (O C) and Nietzschean (A I) contributions

See the below cluster-plane diagram of these classifications, also including my estimates for the positions occupied by a sample of thinkers who could easily be misclassified under the centrism-extremism lens.

This analysis puts universality as the strongest differentiator of the Neo-Enlightenment (high U) from the Pomo-Left and Alt-Right (both low U). Fundamentally, the last two are both identitarianisms, far closer to each other than either cares to understand. The most obvious difference between them doesn’t even rise to the level of this analysis. It is merely which groups are taken as the truly oppressed ones — intersectional hierarchies for the Pomo-Left, whites and men for the Alt-Right. (Think of these oppressed-category variables again as additional axes roughly perpendicular to our cluster-plane, as it would be embedded in a high-dimensional total-memome space.)

One can imagine memeticists of the far future, equipped with hard, neurological measurements analogous to sequenced genomes. What we have here is a toy model of that vision, crafted by the iron tools of intellectual history available today. But iron tools far surpass the broken stones of our occultist ancestors or the loose twigs of our pomo-monkey cousins who haven’t yet died out.