The Deal Trump Should Strike with Putin

The NATO alliance was founded in 1949 to counter Soviet military might.

The standoff between NATO and Russia is increasingly perilous, but there is a way out.

On January 26th of this year, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists reset the Doomsday Clock from 11:57 to 11:58:30 — thirty seconds closer to midnight (a metaphor for planetary catastrophe), indicating a degree of peril for humanity unseen since 1953 and the testing of the first hydrogen bomb by the United States in November of the previous year. In a statement accompanying the move, the Bulletin declared that “The United States and Russia . . . remain at odds in a variety of theaters, from Syria to Ukraine to the borders of NATO” and cited, as another reason (of several more) for the clock’s adjustment, President Trump’s “disturbing comments, made on the campaign trail, about “the use and proliferation of nuclear weapons.” A prominent former Democratic senator would certainly concur with the first point. Sam Nunn, leader of the nonpartisan group Nuclear Threat Initiative, warned that “Russia and the West are at a dangerous crossroads,” and in “a state of escalating tension, trapped in a downward spiral of antagonism and distrust.”

The Bulletin judges the current moment even more dangerous than the thirteen days of the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis. A new cold war between Russia and U.S.-led NATO is underway, and chances for a hot war breaking out look greater than ever: last fall, NATO placed as many as 300,000 ground troops in Europe on “high alert” and has been ramping up deployments to the Baltic states, on Russia’s border. Deepening mutual distrust and bellicose rhetoric, as well as the unnerving proximity of Russian and western military forces and operations (especially in the Baltic region and Syria) heighten the danger of a conflagration that would imperil the survival of civilization as we know it, and serve the interest of no one.

Trump may be saying he wants to get along with President Vladimir Putin, but Russia, for its part, is taking no chances, and has been, for some time, conducting worrisome combat alert drills and large-scale military exercises. It may have just secretly deployed a new cruise missile, in apparent violation of the INF Treaty, which was signed between the United States and the Soviet Union in 1987, and which rid Europe of intermediate-range nuclear and conventional missiles. (Russia contests the accusation; the matter is open to dispute.) Public antagonism between the United States and Russia is higher than ever in recent years: 65 percent of Americans now have an unfavorable view of Russia, which, in 2015, replaced North Korea as the United States’ perceived main enemy; a similar percentage of Russians see a threat in NATO. A year ago, the Pentagon designated Russia as its top threat. Even Trump’s Secretary of Defense, retired general James Mattis, agrees.

Relations between the United States and Russia have been rocky for a long time, but, following the U.S.-supported ouster of Ukraine’s president in 2014 and Russia’s subsequent stealth invasion and annexation of Crimea, they sunk to an unparalleled, post-Cold-War nadir. (Crimea had formed part of Russia from 1783 until 1954, when Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev “gave” it to Ukraine, then a Soviet republic.) In the United States, distrust of and even outright contempt for Putin have, especially since the outbreak of the Ukraine crisis, saturated and at times overwhelmed political discourse about Russia, both in Congress and in the media. The Russian leader is repeatedly characterized as a thug, a killer, a dictator, a tyrant, and so on — as someone, in other words, with whom no dialogue would be possible, let alone desirable. With allegations that Russia “hacked” the 2016 U.S. presidential election, the “Russia threat” has moved from the foreign to the domestic arena, further complicating the prospects for keeping the peace.

All this invective has contrasted with Trump’s oft-stated wishes to “get along with” the Russian leader and Russia generally. Whatever his motives, Trump, since he began his electoral campaign, has consistently repeated words to that effect. To anyone who hopes for a peaceful future — or any future at all — “getting along with Russia” (at least in some basic way) does, in fact, seem like a good idea. Russia and the United States may disagree about many things, but the two countries possessing 90 percent of the world’s nuclear weapons need at least a working relationship. No stable international order can be imagined as long as Russia and the United States remain at such volatile loggerheads.

If, however, as former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger has stated, the “demonization of Vladimir Putin is not a policy; it is an alibi for the absence of one,” Trump’s desire to set things right with Moscow does not constitute a policy and is not even unique. Each of the last three presidents has voiced similar aspirations on entering the White House. Recall, most recently, Obama’s short-lived “reset” with Moscow. Neither Trump nor his team have demonstrated an understanding of what “getting along with Russia” would actually mean. If the Trump stumbles into the minefield of Russian-American relations without a coherent plan, he risks destabilizing NATO and bringing on the very confrontation he seeks to avoid.

What, then, is to be done? Before going into specifics, we should review why we need a renewed détente — a relaxation of tensions — with Russia. A properly achieved détente would serve American interests and buttress American security, and should therefore not be predicated on hoped-for improvements in Russia’s internal situation, or thwarted by animosity to the current occupant of the Kremlin. The hard facts: Russia is the only country with a nuclear arsenal that can annihilate the United States. Russia has demonstrated a growing willingness to use its conventional forces extraterritorially — in Georgia in 2008, in Ukraine in 2014, and now, of course, in Syria. Moreover, in case its conventional forces don’t suffice to deal with an existential threat, Russia has adopted a military doctrine that foresees the use of tactical nukes to “de-escalate” a conflict. (Russia’s envisioning an asymmetrical response make sense, given that it faces, alone, a twenty-eight member alliance.) Simply put, an outbreak of conventional hostilities between Russia and NATO could easily turn nuclear.

There are other, less obvious, but nonetheless cogent reasons we need a new détente. Russia’s cooperation is essential to ensure the nonproliferation of nuclear weapons. (E.g., Russia’s sway with Iran was crucial in concluding the P5+1 nuclear deal with that country.) Russia’s intelligence-gathering apparatus makes it a vital partner in combatting terrorism. (Remember, for example, that Russia’s main security agency, the FSB, warned the FBI about the Boston Marathon bombers, but was ignored.) And lest we forget, Russia’s unique geographic dimensions and its scientific, technological and natural resources would be valuable assets for an ally, but afford the Kremlin the capacity to play an international spoiler role that cannot be discounted. Finally, as President Richard Nixon and Kissinger understood, Russia is well placed to counterbalance an ever more assertive China and mediate with China’s unpredictable ally, North Korea — two other nuclear states that pose great problems for American interests in the Asia-Pacific region.

To dispense with one sure-to-be-raised objection to détente: détente does not mean appeasement. Nixon and Kissinger brought about the first real détente with the Soviet Union while its army faced off with NATO forces in Europe; the SALT I and SALT II treaties and the Helsinki Accords resulted. The 1979 Soviet invasion of Afghanistan disrupted relations, but less than a decade later, President Ronald Reagan, a lifelong enemy of communism who had denounced the Soviet Union as an “evil empire,” enacted his own détente with Mikhail Gorbachev — and ended the Cold War.

For now, at least, Trump can count on his Russian counterpart’s desire to improve relations. Trump has many options, none of which require Congressional approval (at least at this time) and which, doubtless, would not be forthcoming. Putin, less restrained politically, has more latitude, of course. But what exactly would a new détente with Russia look like and how would it begin?

To initiate the détente, the two sides should start small to build trust. Russia could reactivate the Future Leaders Exchange (Flex) program (which it cancelled in 2014) and also lift the ban, which it imposed in 2012, on Americans adopting Russian children, as the speaker of Russia’s Federation Council has suggested. (In play at the time were approximately a thousand adoptions, procedures for which could be resumed.) Simultaneously, the White House could cancel the last round of sanctions (which don’t amount to much anyway) the Obama administration levied against Russia and renounce plans to mount a cyber attack against it for alleged Kremlin-directed hacks related to the 2016 elections. (A bipartisan commission should investigate this matter, and further action could be taken depending upon its findings.) The Kremlin could then reinstate the 2000 agreement, suspended in October of last year, with the United States by which the two sides worked jointly to dispose of excess Russian weapons-grade plutonium, and repeal the law, passed subsequently, that sets forth unrealistic preconditions (e.g., compensation for sanctions concerning the Ukraine crisis) for its reinstatement.

More consequentially, both countries could immediately take their nuclear arsenals off hair-trigger alert. (Possibly, though, only the United States has its weapons set to launch on warning.) Hair-trigger alert status originated in darkest days of the Cold War, when the two superpowers feared they would have to use their missiles or lose them to a surprise first strike, and formed the basis of the MAD doctrine. As things stand now, the United States could fire off its ICBMs within ten minutes of receiving a warning, via radar and satellites, of an incoming salvo of Russian missiles. This is not a foolproof system: accidents and errors (on both sides) have many times (and as recently as 1995) almost resulted in this horrific eventuality. The United States and Russia agreed to a mutual detargeting of their arsenals in 1994; taking the missiles off hair-trigger alert would be the obvious next step.

NATO could then reactivate the NATO-Russia Council, which it suspended in April 2014. “A mechanism for consultation, consensus-building, cooperation, joint decision and joint action,” the Council was established in 2002 so that the alliance and Russia might work as “equal partners on a wide spectrum of security issues of common interest.” The United States and Russia could restore other direct military-to-military ties, also cut off in 2014. These contacts could save the planet from an accidental holocaust.

Such would be the framework within which to resolve some of the most pressing, less complex issues between the United States and Russia. The prospects for a broader rapprochement, however, rest on a reassessment, by the United States and its NATO allies, of NATO’s stance vis-à-vis Russia — and on taking an honest, impartial look at the genesis of the present standoff, which originated with the Ukraine crisis but which has to do with the alliance’s post-Cold-War strategy as a whole dating back to the 1990s.

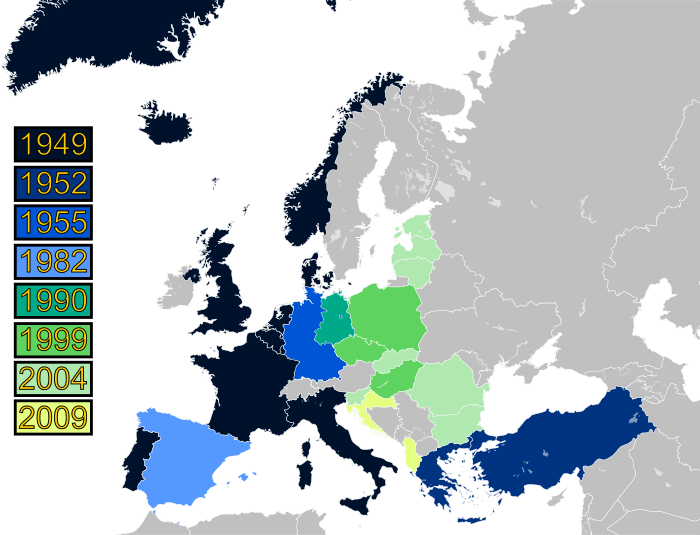

The NATO alliance was founded in 1949 to counter Soviet military might. In 1990, as this might was diminishing with the pan-Soviet woes that came with Perestroika, and when the United States needed Soviet assent to allow German reunification, the United States pledged (orally) to the Soviet government “iron-clad guarantees” that NATO would not expand eastward. (This pledge should not be a matter of dispute: “hundreds of memos, meeting minutes and transcripts from U.S. archives” attest to it, as do official papers released by former Chancellor Helmut Kohl of Germany.) NATO, of course, broke its promise. Since then, it has expanded in four main waves, under both Republican and Democratic administrations and against the objections of Russian leaders, from Mikhail Gorbachev to Dmitry Medvedev to Putin. (Montenegro is the next country to join.) Its twenty-eight members now include former Soviet satellite states in Eastern Europe, and three former Soviet republics — Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia. Moreover, in the Bucharest Summit Declaration of 2008, NATO promised to induct, one day, Ukraine and Georgia.

An understandable historical fear of Russian domination ensured an array of countries in Central and Eastern Europe willing to join NATO, but that does not mean expanding the alliance was a prudent move. Here we should remember the words of George F. Kennan, the master American diplomat who authored the Cold-War-era containment policy and called the enlargement of NATO a “tragic mistake.” Kennan, in 1997, predicted that the planned expansion would spark a “bad reaction” from Russia, and warned of a resulting “new cold war, probably ending in a hot one” and the death of democracy in Russia. More recently, the renowned historian of international relations, Michael Mandelbaum, described the alliance’s growth as “one of the greatest blunders in the history of American foreign policy.” I concur, and have argued repeatedly, and as far back as 2002, that NATO’s expansion would poison relations and set off a new confrontation with Russia. Oft-heard rhetoric that NATO is a “defensive” alliance has meant little to Russia, which has faced the deployment of troops, armaments, matériel, and intelligence-gathering infrastructure right up to its border. What counts are military capabilities, which constitute a concrete reality, whereas declarations of peaceful intent are just, well, words.

The upshot: NATO’s expansion has convinced Russians that the west regards it as an enemy, justified the Kremlin’s vast military buildup, turned a good number of average Russian citizens against the United States, and bolstered Putin’s popularity. It has reawakened Russian apprehensions of invasion from the west (which happened twice in the preceding century alone).

And lest we forget, Ukraine and Georgia remain on NATO’s waiting list. The mere possibility that these two countries might join the alliance has already cost lives. There is good reason to think that the supportive overtures of the George W. Bush administration to Georgia, backed up by the 2008 Bucharest Declaration, prompted Russia to act preemptively and respond to Georgia’s incursion into South Ossetia (then a breakaway republic within Georgia) with its brief invasion of the country that year. By creating a “frozen” territorial conflict in Georgia, Russia would thwart for a long time, at least, any further moves by NATO to bring it into the alliance.

The next theater of conflict would be Ukraine, which former National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski, as far back as 1997, identified as “a new and important space on the Eurasian [strategic] chessboard.” In late 2013 President Viktor Yanukovych (not entirely an ally of Russia, but basically compliant to Moscow) decided, at least temporarily, to defy his public’s ardent wishes and delay signing a highly popular Association Agreement (ostensibly a trade pact) with the European Union. Moscow had opposed the Agreement, which also just happened to foresee a “gradual convergence [between the European Union and Ukraine] in the area of foreign and security policy, including the Common Security and Defense Policy.”

(See Title II, Article 7. The implication was clear: the Agreement was a stepping stone to, either, Ukraine’s renunciation of its neutral status, or to eventual NATO membership. A glance at the similar lists of member countries for the E.U. and NATO should dispel any doubts.)

Yanukovych’s refusal to sign the Association Agreement ignited the Euromaidan protest movement, which morphed into an armed revolt that overthrew him in February 2014. A pro-American leadership took over and repealed the statute enshrining Ukraine’s non-bloc (neutral) status in the constitution, and renewed calls to join NATO. Days after Yanukovych’s toppling, Russia, encountering no real resistance, seized the Crimean Peninsula, home to its Black Sea fleet. (Russia had been leasing, long-term, the Sevastopol port from Ukraine.) War then broke out in Ukraine’s mostly Russian-speaking, partly ethnic Russian eastern region, the Donbas, with Moscow covertly supporting the rebels. As of December 2016, according to the United Nations, almost ten thousand had perished in the conflict.

Russia’s decisive reaction to a clumsy Western attempt to wrest Ukraine from its orbit should surprise no one. Ukraine’s land border with Russia stretches some 1,300 miles and comes within five hundred miles of Moscow. Russia arose as a nation from ninth-century Kievan Rus, the historic heartland of both countries. From the fourteenth century until 1917, foreign powers, including, especially, imperial Russia, dominated Ukraine; Soviet control lasted from shortly after the 1917 Russian Revolution to 1991. About one out of three Ukrainians speak Russian as a first language, which serves as a lingua franca almost everywhere in the country. (Russian and Ukrainian both evolved from the same East Slavic language.) Mutually beneficial economic ties between Russia and Ukraine, as well as familial relations (including millions of intermarriages) also bind Russia and Ukraine. Accordingly, when fighting broke out in eastern Ukraine, 1.5 million Donbas Ukrainians fled not to Kiev-controlled territory, but to Russia, where they knew they would be well received.

As Putin has it — and there is no reason to doubt him — Yanukovych’s overthrow precipitated Russia’s lightning grab of Crimea (with strategically critical Black Sea port and its majority ethnic Russian population). Russia’s actions violated the 1994 Budapest Memorandums on Security Assurances that Russia (as well as the United States and the United Kingdom) had signed with Ukraine, by which Ukraine gave up its nuclear weapons in return for guarantees of territorial integrity. Russia continues to pay dearly for this move, which has resulted in sanctions, a slowing economy, and economic hardship for its population. Yet it shows no sign of backing down.

How would Ukraine figure into the deal Trump should strike with Putin? Trump would renounce NATO’s promise of eventual NATO membership to Ukraine (and Georgia) in return for Russia’s recognition that both countries, while remaining neutral, would be free to join whatever political and economic blocs they choose. This is essentially what both Kissinger and Brzezinski have already proposed. Full implementation of the stalled Minsk Accords, reached in February 2015 and foreseeing autonomy for the Donbas, would end the conflict in Ukraine’s east. This might prompt a violent reaction against the Ukrainian government from the far-right militias fighting on Kiev’s side in the region. Ultimately, though, that would be an issue for the Ukrainian government, not the United States, to deal with.

Additionally, NATO and Russia would withdraw their militaries to pre-2014 postures. NATO would halt and reverse the deployment of approximately four thousand troops to the Baltic states and Poland. (Stationed on a rotating basis so as not to violate the alliance’s Founding Act with Russia, the troops are intended as a “trip wire” and could not, in any case, halt a Russian invasion of the Baltic countries, which would take as little as sixty hours.) Russia would redeploy forces it has moved close to the Baltic frontier, and take out the short-range, nuclear-capable Iskander missiles it has sent to Kaliningrad, on the Polish border. Both sides would cease conducting provocative military exercises, and Russia would stop sending its fighter jets to violate European airspace and buzz U.S. warships.

The status of Crimea presents a significant hurdle to be overcome. The peninsula officially became part of Russia in 2014. A great majority of both ethnic Russians and Ukrainians in Crimea favor remaining within the Russian Federation. To settle the matter, Russia could agree to hold another referendum, but this time under the auspices of the United Nations. If the results show that Crimea’s population wishes to stay within Russia, as is highly likely, the United States should recognize this, and, of course, the White House should drop the Crimea-related sanctions implemented by executive order. If Crimeans choose to return to Ukraine, Russia should honor their wishes.

More broadly, yet critically for the future, Russia and the United States should resume strategic arms limitation talks. Trump should reverse his position on the New START agreement (signed by Obama in 2010 and scheduled to remain in force until 2021); contrary to what Trump believes, it does not favor Russia.

In any such negotiations, the Russians are sure to raise the U.S. missile defense system now operational in Romania, and the 1972 Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty from which the United States decided to withdrew unilaterally in 2002. (Russia followed suit the day after.) The U.S. government has always maintained that its European “Star Wars” complex is meant to shield the continent against an Iranian attack. A good argument can be made, though, that the missile defense system is more destabilizing than effective and should be considered an offensive weapon. Theoretically, it could be used to shoot down the few ICBMs Russia could launch in the wake of a successful first strike by the United States. Such a strike might seem implausible, to say the least, but, according to the eminent nuclear theorist John Steinbruner, it represents “the only imaginable route to decisive victory in nuclear war.” Hence, Russian strategists must take the possibility of it seriously. Ideally, both sides could sign a new anti-ballistic missile treaty, with agreed-upon exceptions (formerly these included protection for Moscow and an anti-ballistic missile complex in North Dakota), but which could be expanded, if necessary, by mutual agreement. A treaty would require Congressional ratification, though.

With the exception of the treaty (which would have to come later) all the above could be codified in an accord and signed at a summit in either Moscow or Washington.

If Trump chooses not to pursue détente with Russia and continues with the current policy, then he would do well to recall Kissinger’s words: “the test of policy is how it ends, not how it begins.” He might also want to reflect on what President John F. Kennedy said in 1963, after the nearly catastrophic Cuban Missile Crisis: “Above all, while defending our vital interests, nuclear powers must avert those confrontations which bring an adversary to a choice of either a humiliating retreat or a nuclear war.” The détente outlined above would allow us to lessen the risk of such a confrontation.

No time in recent decades has been more perilous than ours. The Trump administration, as well as Congress, should recognize this, and act immediately to reduce the threat to us all.