Indigenous History

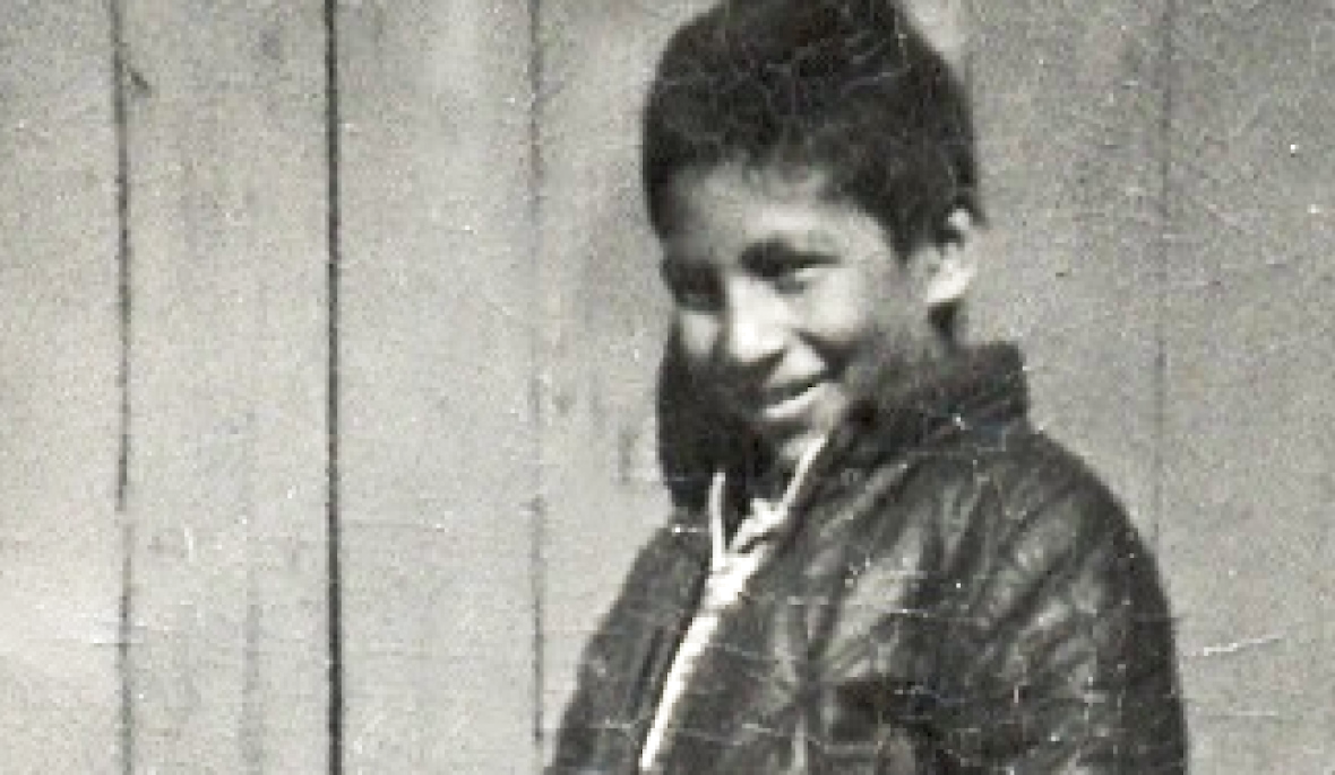

The Lonely Death of an Ojibway Boy

Charlie Wenjack has come to symbolise the deadly horrors of Canada’s Residential Schools. Unfortunately, many details of his tragic story have been misrepresented in the process.

· 19 min read

Keep reading

Hell in North Germany

Ron Capshaw

· 12 min read

Why the Islamic Republic Must Fall

Armin Navabi

· 8 min read

Podcast #292: Social Work Without Stereotypes

Jonathan Kay

· 21 min read

Purity, Profit, and Politics

Steve Salerno

· 22 min read

The Twelve Day War: Truths and Consequences

Adam Garfinkle

· 22 min read

Glamourising Violence at Glastonbury

John Aziz

· 8 min read