Education

Critical Thinking, Reverential Thinking, and Lashing Out

Before we challenge conventions, we must understand and master them.

It has … become hard to express tender feelings, feelings of respect, of awe, of idealization, of reverence.

~Leon Wurmser, The Mask of Shame

When my daughter’s high-school senior-year art-history class began with the kids having to read John Berger’s neo-Marxist book Ways of Seeing, a series of deconstructive and deflationary essays on the history of Western art, I was disconcerted. Starting an art history course with Ways of Seeing is like starting an American history course with Howard Zinn, a history of science with Paul Feyerabend, a history of morality and religion with Nietzsche, or a history of economics with Karl Marx. Critics and dissidents are, of course, worth reading, but they should be read after the student understands and cares about that which is being criticized. Ending a course with critical texts creates perspective. Beginning a course with such texts can inspire contempt, dampen students’ enthusiasm, and promote a smug, dismissive attitude.

A peculiar kind of critical thinking is lauded in the academic mainstream. As one recent survey summarized the state of affairs, “support for critical thinking skills [is] nearly universal, with equally strong support for the teaching of critical thinking at all levels of education.” Entire approaches to fields—such as the mid-century Frankfurt School’s critical theory and its more widely known present-day offspring, critical legal studies, critical pedagogy, critical gender studies and, of course, critical race theory—have arisen whose raison d’être is to challenge old orthodoxies. When conservatives and other defenders of the establishment have fought back against these radical approaches, supporters have claimed that the rearguard is trying to suppress critical thinking. “If keeping kids out of school isn’t possible, the [Republican] strategy is to intimidate teachers out of any lesson that could provoke critical thinking,” a typical example of this strategy argues.

How much actual critical thinking—as opposed to the encouragement of a progressive monoculture—these avowedly “critical” perspectives promote is an open question, one that has been raised by many who have observed that such “critical thinkers” are often themselves remarkably sensitive to criticism, brooking no dissent and often resorting to ad hominem attacks and outlandish accusations instead of arguments. Indeed, one of the most notorious installments in the “critical” canon, Herbert Marcuse’s essay on the subject of “Repressive Tolerance,” serves as a kind of blueprint for today’s war on free speech in the name of ostensibly higher “progressive” ideals.

Such overreach aside, critical thinking is, in fact, a necessary component of a well-rounded education and an indispensable prerequisite for democratic citizenship. The problem, however, is in putting the cart in front of the horse: one cannot be critical in any intelligent fashion before one has a basic command of and appreciation for the thing at which such criticism is directed. This contention is supported by abundant research showing that a generic “critical thinking” skill, independent of domain-specific knowledge, does not exist.

That this is so should be obvious upon reflection. Consider a domain such as the game of chess. Without critical thinking that challenges the status quo, innovative moves that defy convention and drive the evolution of the game would simply never happen. But teaching critical thinking about chess without first teaching the rules, the typical strategies, the basic openings, rules of thumb would be absurd. Chess players can only innovate effectively when they know and understand the game.

We can also arrive at the same basic insight from a more theoretical vantage point. In the 1950s, the Harvard psychologist Lawrence Kohlberg, drawing on the work of the famed Swiss child psychologist Jean Piaget, delineated three principal stages of individual moral development: preconventional, conventional, and postconventional. In outline: We are born ignorant of the adult world and its conventions and begin to obey such conventions only because adults around us force or manipulate us into doing so; we come to learn, appreciate, and support the reasons behind such conventions; and finally, we may begin to question and challenge these conventional norms.

Children begin, according to Kohlberg, at the preconventional stage. They don’t know the basic rules and norms of society. They may speak out of turn, blurt out inappropriate remarks, play with their food, bite peers, and scream and cry in public. They do these things not to be obnoxious, but because they simply do not understand social standards and expectations. Furthermore, when they do learn to comply, their compliance is driven not by an appreciation of rules or norms, but because they crave rewards and fear punishments. Their behavior is self-interested, in a narrow sense. It is not norm-driven, but outcome driven.

As they enter their second decade of life, however, most children move to the conventional stage of development, in which they develop an autonomous understanding of social standards. Tommy refrains from hitting Stan because he has internalized the norm that one should not hit others, not because he calculates that hitting Stan might cause his father to take away his favorite toys. Many people live out the rest of their lives at the conventional stage and become society’s backbone, upstanding citizens who follow the rules and norms of society.

Some, however, proceed to enter the postconventional stage, whereupon they apply second-order reasoning to rules and norms. They question the justness of the norm itself, using deeper social goals and abstract universal principles such as liberty, equality, fraternity and so on to interrogate society. As a result, they may reach moral conclusions that are markedly different from the status quo; they might become abolitionists in a slave-holding society or champions of pro-life policies in a country where abortion is legal and widely accepted. Without some postconventional people in a society, norms and institutions stagnate and unjust laws and expectations remain unchallenged.

But there is an important wrinkle in this framework: to an outside observer, a person in the preconventional and postconventional stage might be indistinguishable because their norm-flouting behaviors are superficially identical. But on the inside, something very different is happening. In the preconventional case, the person is not motivated by informed skepticism, but impulsiveness and ignorance, whereas, in the postconventional case, the person is motived by a learned critical attitude. The integral theorist Ken Wilber calls mistaking pre for post the “pre/trans fallacy.”

Consider some examples in which the pre/trans fallacy is significant: (1) Mistaking art that is genuinely naïve and primitive such as a child’s stick figure for art that is superficially childlike, such as the primitivism of an acknowledged master like Jean Dubuffet; or (2) Mistaking the speech and writing of a child who has not yet mastered the conventions of grammar and usage with the masterful mangling of such conventions by brilliant stylists such as James Joyce or Russell Hoban. The preconventional child does not know any better; he cannot do anything other than what he does. His sentences, his paintings, are a result of his limitations. But the postconventional master, thoroughly trained and learned, can make deliberate and calculated aesthetic choices, some designed to depart from traditional norms for great effect.

Nor, and this is crucial, can or should the preconventional child ever be taught to paint like Picasso or write like Joyce. There is a reason art and writing classes begin by exposing students to traditional greats, those who display excellence at the classical rules: Before one challenges conventions, one must first master them—and, more than master them, one must learn to love them. Only then does the student begin to develop an appreciation of what is at stake in challenging tradition, in seeking to move beyond.

Today, a version of the pre/trans fallacy is often embedded in the way children are educated. They are being taught to think postconventionally, i.e., critically, before they have learned to think conventionally. They are taught to criticize before learning to understand and appreciate. And then they are being praised by ideologically blinkered adults for having attained a shallow pseudo-maturity that actually consists in parroting critical words and phrases the full meaning of which they cannot comprehend. Students indoctrinated from an early age, for example, in the over 4,500 schools that have adopted curricula built upon the historically inaccurate and largely resentment-driven “1619 Project” are being taught to condemn their own country before developing any particular commitment to it or appreciation of its pathbreaking ideals and historical accomplishments.

There is a better way to structure the learning process. Critical thinking is of course a necessary skill, but there is a more basic, more fundamental style of thinking: It is called reverential thinking. And it must precede critical thinking in the same way that an internalization of norms must precede an intelligent criticism of them.

Reverential thinking is about cherishing and honoring that which already exists. It is not merely the ability to master social conventions and traditions, but also the capacity to venerate, cherish, and honor that which we already have. It is thus a style of deferential thinking that encourages people to value tradition; and to value tradition, one must understand tradition.

Just as people vary in their innate capacity to think critically, so too people also vary widely in their facility with reverential thinking. Some people are perpetually grateful, full of joie de vivre, and enthusiastic about that which is. They naturally venerate that which is their own, from their spouse to their children, from their jobs to their hobbies, from their local community to their nation. They live in a state of enchantment. These people are temperamentally well-suited to reverential thinking.

But, of course, temperament alone is not enough. One cannot understand one’s cultural inheritance simply by excitedly exploring and admiring one’s local slice of civilization. All of us know those individuals who think their local deli or red-sauce Italian joint is the best there is simply because it is a pretty good, nearby one they happen to frequent. They are missing out on others they might better enjoy, if they simply knew where to look. This example may be trivial, but there is nothing trivial about the broader pattern of provincialism it exemplifies.

As a nation, we have an interest in combatting that lack of curiosity and ambition to expand one’s boundaries, an interest in cultivating a civilization of seekers, a citizenry that appreciates the finer things in life. Reverential thinking is therefore not about cultural chauvinism or localism. It is about learning in Matthew Arnold’s famous phrase, “the best which has been thought and said in the world.”

Consider the example of chess once again. Of course a teacher has to teach the rules, the openings, and other basics (“a knight on the rim is dim”). But this will not matter a jot unless the teacher manages to instill a deep appreciation and love of the game. Students should learn beautiful and instructive games from the entire history of chess, from Morphy to Carlsen.

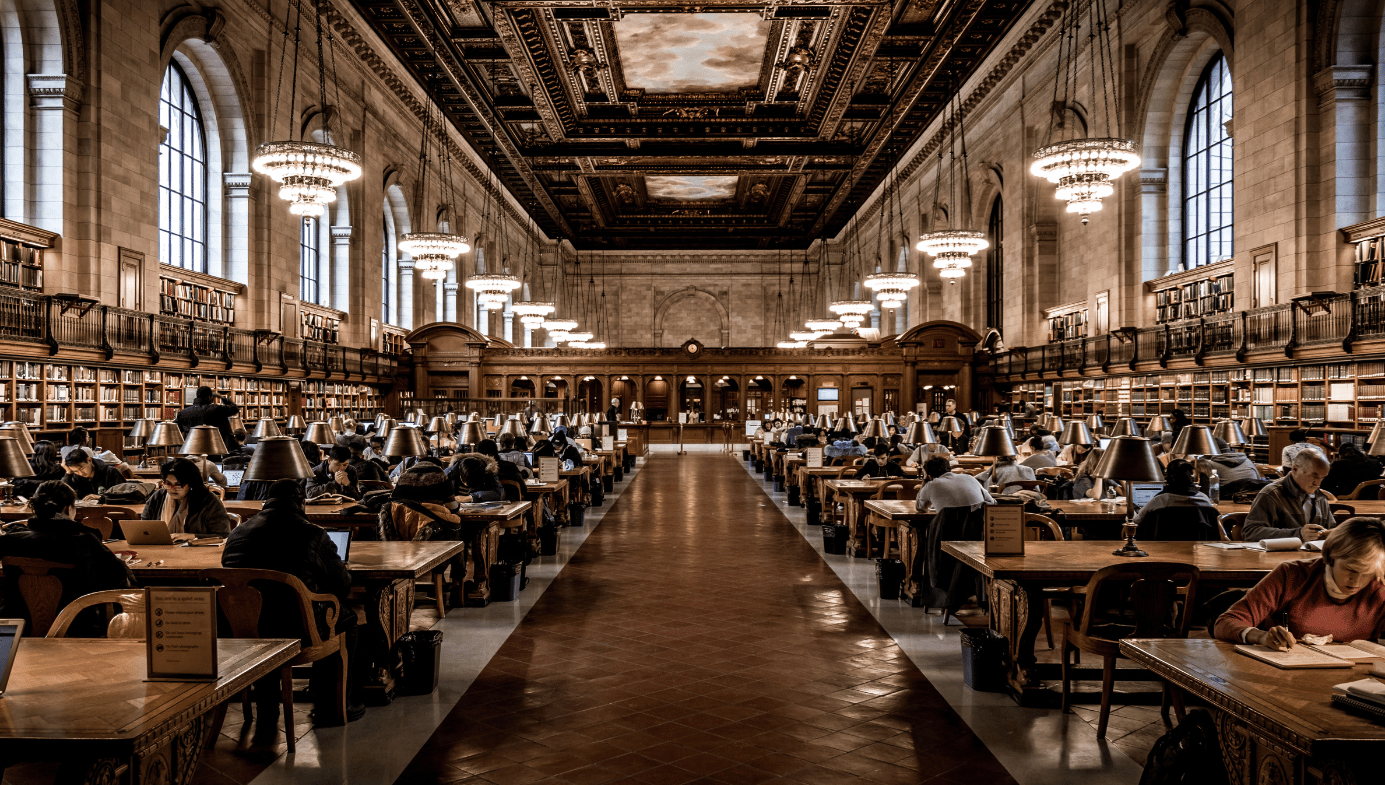

And so, like a monk in a monastery devoting his life to the study of scripture, we should first do the hard work of becoming reverentially aware of tradition. This is the role and primary function of education: To instill in students the ability, the knowledge, the awareness to stand in awe before humanity’s greatest achievements—the finest literature, art, music, philosophy, and science. A nation or a world composed of reverential thinkers is one in which people are hesitant to desecrate that which has long been exalted because they understand how much it takes to build a great civilization and how little it takes to bring one down.

Only after comprehending and revering tradition can a student effectively criticize. Only then does critical thinking become a potential instrument of progress and a useful counterweight to blind idolatry. Only when people have learned to worship, informed by a sense of appreciative understanding, can they begin to subject their creed to sincere scrutiny and doubt.