Art and Culture

The Racism Treadmill

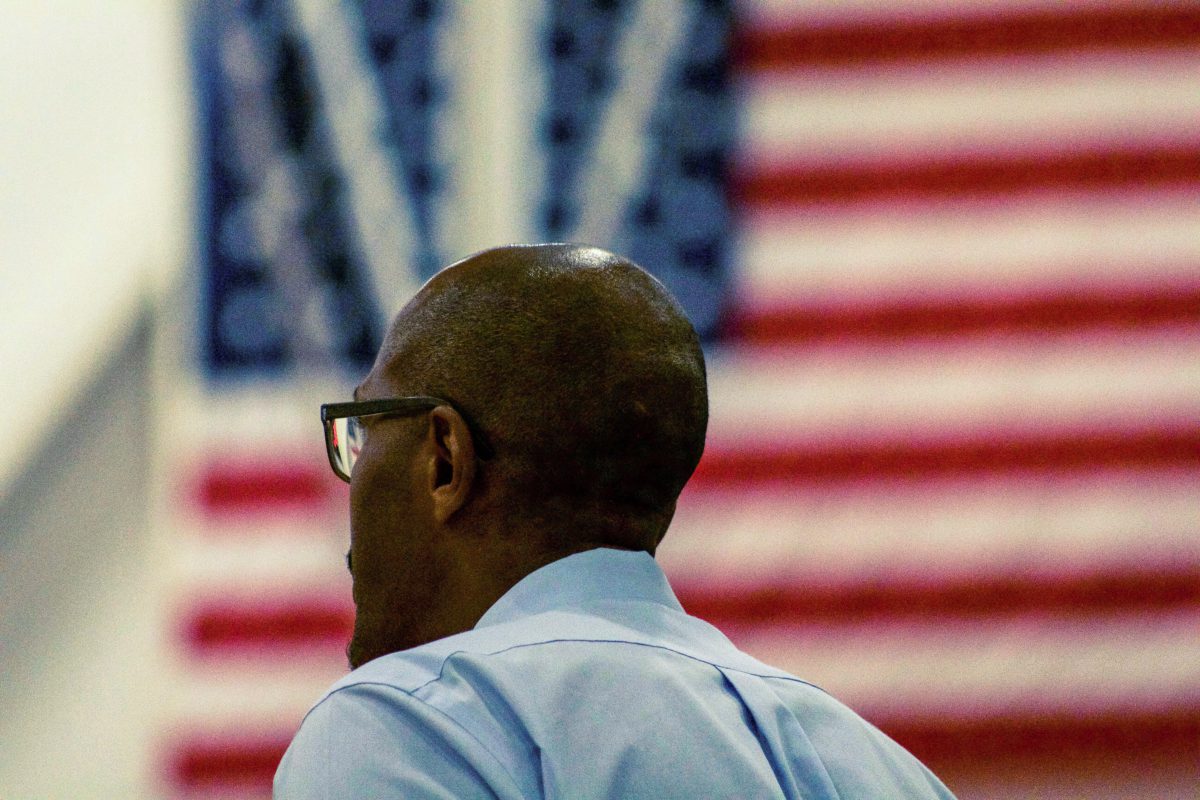

If racism still looms large in our social and political lives, then, as one left-wing commentator put it, “progress is debatable.”

The prevailing view among progressives today is that America hasn’t made much progress on racism. While no one would argue that abolishing slavery and dissolving Jim Crow weren’t good first steps, the progressive attitude toward such reforms is nicely summarized by Malcolm X’s famous quip, “You don’t stick a knife in a man’s back nine inches and then pull it out six inches and say you’re making progress.” Aside from outlawing formalized bigotry, many progressives believe that things haven’t improved all that much. Racist attitudes towards blacks, if only in the form of implicit bias, are thought to be widespread; black men are still liable to be arrested in a Starbucks for no good reason; plus we have a president who has found it difficult to denounce neo-Nazis. If racism still looms large in our social and political lives, then, as one left-wing commentator put it, “progress is debatable.”

But the data take a clear side in that debate. In his controversial bestseller Enlightenment Now, Harvard psychologist Steven Pinker notes a steep decline in racism. At the turn of the 20th century, lynchings occurred at a rate of three per week. Now, racially-motivated killings of blacks occur at a rate of zero to one per year.1 What’s more, racist attitudes that were once commonplace have now become fringe. A Gallup poll found that only 4 percent of Americans approved of marriages between blacks and whites in 1958. By 2013, that number had climbed to 87 percent, prompting pollsters to call it “one of the largest shifts of public opinion in Gallup history.”

Why can’t progressives admit that we’ve made progress? Pinker’s answer for what he dubs “progressophobia” is two-fold. First, our intuitions about whether trends have increased or decreased are shaped by what we can easily recall—news items, shocking events, personal experience, etc. Second, we are more sensitive to negative stimuli than we are to positive ones. These two bugs of human psychology—called the availability bias and the negativity bias, respectively—make us prone to doomsaying, inclined to mistake freak news events for trends, and blind to the slow march of progress.