Top Stories

The Complicated Legacy of Colonial Contact

The effects of colonial contact, and the process of acculturation on small-scale societies, can be quite unpredictable.

“There is…no simple progression from “traditional” to “modern,” but a twisting, spasmodic, unmethodical movement which turns as often toward repossessing the emotions of the past as disowning them.” – Clifford Geertz, The Interpretation of Cultures, 1973

Intercultural contact can be quite precarious. Interactions between different populations with diverse languages, cultural norms, and social institutions have sometimes led to mutually beneficial exchanges of goods and technology, but they can also precipitate unforeseen conflicts. Early encounters between people in small-scale societies and state representatives and missionaries all too often led to regrettable misunderstandings – or conflicts of interest – that ended in tragedy.

In anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss’s memoir Tristes Tropiques (1955), he described the embittered relationship between Protestant missionaries and the native Nambikwara hunter-gatherers of Brazil during the early 20th century. In 1933, soon after the missionaries arrived, the Nambikwara helped the missionaries build a house and plant their garden. In return, the missionaries gave them some unspecified gifts, which the Nambikwara considered inadequate. A few months later, a Nambikwara man went to the mission with a fever and was publicly given two aspirin tablets. He later developed congestion of the lungs and died. The Nambikwara, themselves expert poisoners, concluded that he had been murdered, and launched a retaliatory raid that killed six people at the mission, including a two-year old child.

The influence of outsiders can also increase tensions between native groups. In anthropologist Gilbert Herdt’s volume on The Sambia (2003) of New Guinea, he wrote of how Christian influence led Wunyu-Sambian men – who traditionally did not bathe – to begin bathing with soap and water. This was perceived as a theft of customs by the neighboring Seboolu men, who practiced a traditional purification ritual using water, and led to a war, which was eventually stopped by Australian patrol officers.

During the colonization of the Americas in the 17th century, as the Iroquois lost many of their people due to the influx of disease, they expanded their long-standing hostilities with many rival native societies such as the Huron. In American Colonies (2001), historian Alan Taylor wrote that,

Dutch guns enabled the Iroquois to take the offensive, while Dutch-introduced pathogens increased deaths, escalating the frequency, distance, bloodshed, and captive-taking of mourning wars as the Iroquois desperately tried to restore numbers and spiritual power, lest both ebb and their enemies triumph. (Taylor, 112)

The Iroquois killed rival Huron warriors, while abducting women and children to incorporate into their society. They also burned down many Huron villages to prevent them from returning home. Violent conflict between the Iroquois and their neighbors certainly predated European colonization, but the introduction of guns and new diseases likely exacerbated warfare.

Contact with powerful outside societies can also radically change the existing power dynamics among native populations. This also creates opportunities for more marginalized populations to take advantage and form new alliances. In The Cambridge history of the Native Peoples of the Americas (1996) edited by Richard Adams and Murdo MacLeod, anthropologist Richard Diehl wrote,

When Hernando Cortés (or Cortéz) arrived in their territory in 1519, the Totonacs of Cempoala dominated the region but were in turn under Aztec subjugation. They quickly turned on their highland overlords by becoming Cortés’s first Indian allies, without whom he never could have conquered the Aztecs. (Adams & McLeod, 185).

The effects of colonial contact, and the process of acculturation on small-scale societies, can be quite unpredictable. In anthropologists Michael Gurven and Hillard Kaplan’s 2007 paper ‘Longevity Among Hunter-Gatherers’, they found that Agta forager populations of the Philippines and Yanomamo horticulturalists of the Amazon saw their mortality increase, with increased deaths from diseases, after significant contact with state societies. However, they also found that among most acculturated hunter-gatherer populations, such as the !Kung of the Kalahari Desert, the Hiwi of Venezuela, and the Aché of Paraguay, there was ultimately reduced mortality and an increase in life expectancy after prolonged contact, due to factors such as greater access to sanitation and medical supplies.

Yet, improved health conditions can sometimes mask other social problems. While the settled !Kung of the Ghanzi district in Botswana saw their life expectancy increase after they started farming, anthropologist Mathias Guenther also noted that they subsequently began to refer to themselves as the ‘kamka kwe, which in the Naro language means ‘weak or inconsequential people’, due to comparing themselves to larger neighboring societies. Some populations that have seen overall mortality rates decline, such as the Hiwi and the Aché, have experienced decades of violent interactions with local farmers, including massacres of members of these indigenous populations.

While initial contact can often exacerbate the amount of killing and warfare, in the long-run there tends be a significant decline in rates of violence after contact with states. In The Anthropology of War (1988), anthropologist R. Brian Ferguson wrote,

It is often assumed that contact results in an ending of native warfare. Ultimately, it usually does. However, my own investigations of war on the Northwest Coast, in Amazonia, and elsewhere, indicate that the initial impact of contact is to greatly aggravate warfare, and to introduce numerous changes in its practice and social significance. (Ferguson, iv)

The conflict between the Wunyu-Sambian and Seboolu men offers a clear illustration of this, where outside contact contributed to new sources of conflict, until New Guinea tribal warfare was ended by colonial intervention, when the Australian colonial government began arresting warriors. Anthropologist Gilbert Herdt wrote in his book on The Sambia that, “Through a sequence of complex moves,” an Australian patrol officer, “tricked the warriors into assembling and then he handcuffed them.” They were jailed for a few weeks, then released and warned never to fight again. Herdt adds that, “This resulted in permanent peace.”

Homicide rates in small-scale societies sometimes decline significantly when the intervention of state institutions can help resolve disputes. In Richard Lee’s volume on The Dobe Ju/’hoansi (1984), also known as the !Kung, he describes a high homicide rate from 1920-1955, with most killings occurring due to long-running feuds and revenge. With the assistance of outside mediators, and a court system that proved very popular among the Ju/’hoansi, homicides began to decline.

In some cases, colonial influence can prove extremely popular among one segment of a population, while being viewed with disdain and resentment among another. In The Cassowary’s Revenge (1997), anthropologist Donald Tuzin described how Christian influence led to the decline of the ‘men’s cult’ that had previously dominated social life among the Ilahita Arapesh of New Guinea. The cult would frequently terrorize and deceive the women and children, and while many of the women converted to Christianity and viewed the decline of the cult as a welcome development, many of the men resented their diminished status and the loss of their sacred rituals and rites. Tuzin says that the decline of the cult led to increases in alcohol consumption and wife beatings.

While their decline in status angered some of the men, there may have also been a sense of relief that many of the dysphoric and traumatic rituals that they had previously practiced, such as penile bleeding, beatings, and even ritual murder, were no longer conducted. In the volume Rituals of Manhood (1982), Tuzin wrote that, “in discussing these matters with Arapesh informants I was often struck by the negative valuation that they themselves placed on certain of their ritual customs: the act was “cruel,” though the intention frequently was “not.”

Many seemingly important practices found across numerous small-scale societies, such as ritual infanticide, cannibalism, and head-hunting raids, were sometimes voluntarily abandoned by the people themselves after contact. In anthropologist Robert Edgerton’s book Sick Societies (1992), he wrote that, “Various ethnographers have observed that people in small, traditional societies may willingly give up one of their apparently important practices after only minimal contact with Christian missionaries or European administrators.” Anthropologist George Murdock, who compiled the Ethnographic Atlas and helped create the Standard Cross-Cultural Sample, argued that preferences for more efficient medicines and technology and more effective means of conflict resolution were universal across cultures; in the 1965 volume Culture And Society, he wrote,

Ethnography demonstrates that, when faced with expanded possibilities of cultural choice, all peoples reveal a preference for steel over stone axes, for quinine and penicillin over magical therapy…for animal and vehicular transport over human porterage, for improvements in the food supply which enable them to rear their children and support their aged rather than killing them, and so on. They relinquish cannibalism and head-hunting with little resistance when colonial governments demonstrate the material advantages of peace (Murdock, 148).

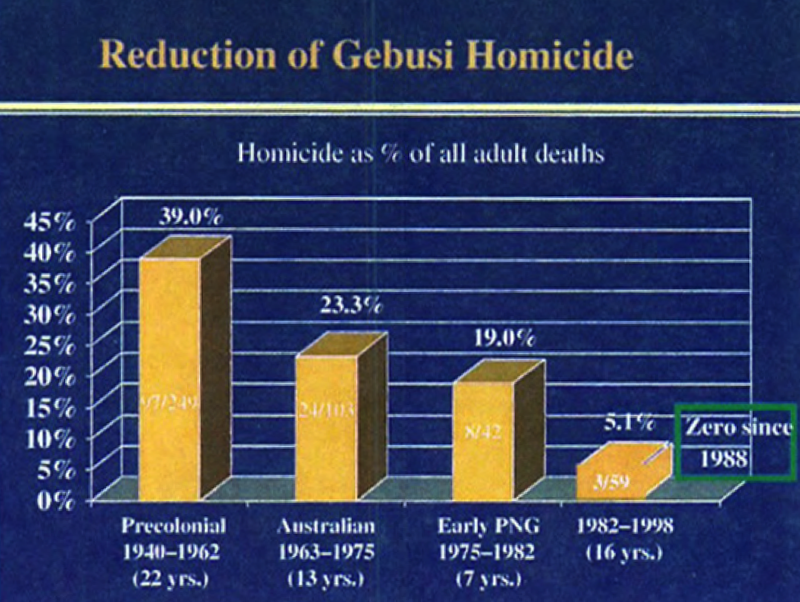

Perhaps no society better illustrates how complex the interactions between small-scale societies and colonial influence can be than the Gebusi of New Guinea. During the middle of the 20th century, the Gebusi had one of the highest recorded homicide rates among contemporary populations, with 39% of adult deaths due to homicide. At least 65% of Gebusi men had committed homicide, and most of these occurred in the context of sorcery allegations. However, in the 1980’s, many Gebusi began converting to Christianity, and voluntarily moved their village settlement to be closer to the Catholic Church, which is itself near government facilities such as a school and market. Anthropologist Bruce Knauft noted that the Gebusi subsequently had zero recorded homicides from 1988-2008.

Intercultural contact is a heterogeneous process that often defies easy categorization. The responses to contact by many indigenous people across various societies is diverse and multi-faceted. As I described in a previous article for Quillette, the Batek hunter-gatherers of Malaysia, for example, have a long history of being attacked and enslaved by larger, neighboring Malay societies in the region. At the same time, as anthropologists Ivan Tacey & Diana Riboli note, they would “frequently recount their nostalgic memories of British doctors, administrators and army personnel visiting their communities in helicopters to deliver medicines and other supplies.”

The long history of intercultural contact is not simply a story of domination but one of interaction between diverse cultures. To understand this history, it’s important to recognize the agency of people in small-scale or indigenous societies, and the manifold ways they responded to contact with outside populations. Encounters with powerful foreign societies often impelled complex dilemmas on native cultures, precipitating difficult decisions and variable outcomes. Some societies were devastated by disease and warfare, while others voluntarily adopted new social norms and productive technology they considered desirable. The legacy of colonial contact is complex, and does not lend itself to singular narratives or easy answers.