Canada

How Canada’s Cult of the Noble Savage Harms Its Indigenous Peoples

Generations of Indigenous children were forcibly sent to church- and government-run residential schools, which systematically stripped away their culture and language.

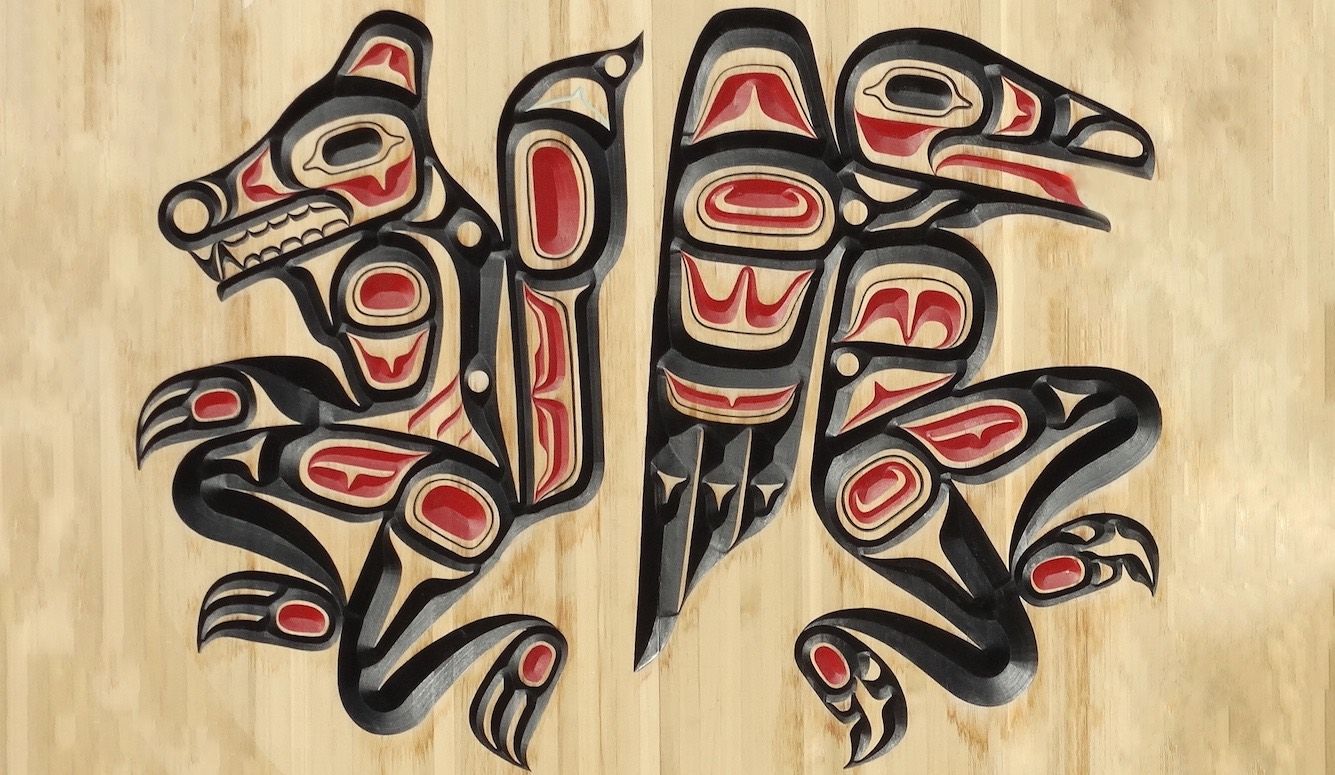

A few months ago, I spoke at a small academic conference in Toronto about the future of Canada. As with many events of this type in my country, it began with sacred rituals. An Ojibway elder, described to us as a “keeper of sacred pipes,” took to the podium and showed us a jar of medicine water. In her private rituals, the elder explained, she would pray with this water, and talk to it as she smoked her pipes. After this, she instructed us to join her in “paying respect to the four directions”—which required that we stand up and face the indicated compass point, moving clockwise from north to west as she performed her rituals. “With this sacred water, we smudge this space,” she said. “Let us live the lesson of being in harmony with all creatures.”

Then the elder instructed us to bend down, touch the floor, and say migwetch—thank you, in her Ojibway language—to signal our gratitude. The room was full of middle-aged former politicians who, like me, did not want to seem impolite. But after turning in place on command, this floor-touching business seemed a little much. Nevertheless, the men and women around me began hunching downward, extending palms toward the floorboards, until the whole room resembled a congregation at prayer. There were only perhaps a half-dozen of us who hesitated slightly, and were now anxiously casting eyes about the room for co-conspirators.

I tried to look nonchalant as I remained upright. But I wondered whether some conference official would call me out for this act of defiance. Or perhaps someone would snap a picture and put it on Twitter. I felt like Cosmo Kramer from Seinfeld, when confronted by a pair of strangers after refusing to wear a ribbon during an AIDS walk.

But there also was something more serious at play—for the whole scene was a microcosm of a larger cultural phenomenon that’s been playing out in Canadian society for generations. How did it come to be, I wondered, that this room full of intellectuals and policy-makers, plucked from among one of the most secular nations on earth, should be called upon to genuflect en masse to animist spirits?

Ask this question on social media, and culture warriors on both sides will provide plenty of snappy answers. But to answer properly, and constructively, requires at least some understanding of the distorted way in which white Canadians—and Westerners, more generally—have come to conceive of Indigenous peoples. And these distortions are producing disastrous effects on the very Indigenous societies that we’re all trying to help.

* * *

Racism has taken many forms throughout Western history. But typically, it originates broadly with the idea that one race ranks as inferior to another on some imaginary index of human worth. White assertions of supremacy over blacks is the most obvious and enduring example: Even after it was no longer legal to buy and sell black people as property in North America, this hierarchy remained encoded in law. As recently as the 1960s, miscegenation was still a crime in some parts of the United States; and a black man risked being lynched if he was seen with a white woman.

In the case of white supremacist attitudes toward Indigenous peoples, however, the history is more complicated. In both Canada and the United States, there has been a long history of intermarriage between white and Indigenous peoples—so much so that a legally recognized category (Métis) was created in Canada to describe the descendants of First Nations people who joined with French voyageurs.

While slaveholders appealed to pseudo-science to denigrate blacks as lazy and simple-minded, the attitudes of white explorers and traders encountering Indigenous peoples were more mixed. Written accounts, such as those left by eighteenth century explorer Pierre de La Vérendrye, express admiration for the toughness, survival skills, and ingenuity of the Indigenous groups they encountered. Jean-Baptiste Colbert, France’s Minister of Marine during the reign of Louis XIV century, went so far as to urge a “fusion” between French explorers and the Aboriginal population, as an instrument to expand France’s influence.

In the frozen expanses of northern Canada, the impulse toward racism was blunted the hard way, because whites who dismissed the knowledge and guidance of local Indigenous communities often would pay the ultimate price for their arrogance. As New Yorker writer Kathryn Schulz noted in a recent essay about the Arctic:

John Franklin’s entire crew died of starvation and exposure in an area where, for generations, the Inuit had raised their children and tended their elderly. It was possible to live and even thrive in the Arctic—but, steeped in the racial prejudices of colonial England, almost all of Britain’s polar explorers declined to imitate indigenous ways of travelling, hunting, eating, and staying warm. Everywhere else in the former British Empire, English chauvinism led to the death of untold numbers of native people. In the Arctic, English chauvinism led to the death of untold numbers of Englishmen.

Both Canada and the United States eventually imposed policies aimed at annihilating Indigenous cultural practices and languages. Yet, paradoxically, these same white-dominated societies would also lionize individual Indigenous chiefs, warriors, spiritual leaders, artists and writers. In Canada, none would become more famous than the self-proclaimed “Wa-Sha-Quon-Asin, Grey Owl, North American Indian, champion of the Little People of the Forests.” During the 1930s, in fact, Grey Owl would become the most famous Indigenous writer in the world—despite the fact that (as the world learned after his death) he was actually a British immigrant from Hastings, England named Archibald Stanfield Belaney.

Grey Owl was a gifted, if somewhat didactic, middlebrow writer who produced sentimental narratives about the Canadian wilderness he roamed throughout his adult life. Even if he’d been honest about his identity as a white man, he might well have made a successful living from his books. But the ingredient that made him a true literary star—both in Canada and internationally—was his allegedly Indigenous bloodline, which editors and readers alike believed gave him special insight into the secrets of nature and the animal kingdom. Having grown up as an English schoolboy fascinated by First Nations and their habitats, Grey Owl knew exactly what his readers wanted: gauzy sketches of a simpler, more noble, more sacred world than the smog-choked cities they inhabited. Sadly, the simplistic and infantilizing stereotypes he peddled persist to this day.

Canadians now take for granted the portrayal of Indigenous peoples as conscientious, pacifistic stewards of the earth. But as University of Alberta literature professor Albert Braz has noted, this conception of Indigenous life didn’t become popularized until the early twentieth century. Prior to that, it was just as common to hear tales of Indigenous hunters (and fighters) performing wanton slaughter, annihilating other tribes, or whole species of animals. It was Grey Owl, a white man, who led the campaign to rebrand Indigenous peoples as innocent children of the forest. He even went so far as to suggest that it would be preferable for Indigenous peoples to disappear from the planet rather than be “thrown into the grinding wheels of the mill of modernity, to be spewed out a nondescript, undistinguishable from the mediocrity that surrounds him, a reproach to the memory of a noble race.”

In the Canadian magazine Forest and Outdoors, through which Grey Owl first attained a wide readership, editors called the man a “philosopher of the wild.” The language used to describe him in these interwar-era publications was borrowed from Christianity—identifying the emerging author as an ambassador from a real-world Eden. “Aboriginal races uncontaminated by the influence and excessive demands of the white man, or his civilized coloured cousins, take wildlife as did their remote progenitors,” wrote the editors. “Pagan people have yet to be discovered who hunt for the pleasure of killing.” At a time when many of Grey Owl’s readers were still very much alive to the utopian promises of Marxism, he also presented aboriginal societies as communities in which bounty was freely shared and no one fretted much about personal property.

More than half a century after his death, Grey Owl’s influence would reassert itself as a powerful undercurrent in Canadian intellectual life. But as the twentieth century wore on, readers lost their fascination with his stories. Most of the immigrants who came to Canada after World War II were chasing jobs, not wilderness adventure. And they congregated in cities, not farms or logging camps. The dominant media of the postwar age were TV and film, much of it pumped out by American studios peddling their own racist stereotypes of Indigenous peoples as sadistic militia.

In the United States, the rise of the interstate highway system is credited with bringing blacks and whites into closer contact, indirectly paving the way for the civil rights era. But the development of modern Canadian transportation networks arguably had the opposite effect—because many rural Indigenous communities instantly became flyover country. Meanwhile, these communities were being transformed into permanent lumber-framed settlements that lacked the romantic appeal of the quasi-nomadic First Nations world mythologized by Grey Owl. Then, as now, alcohol, processed foods, and welfare dependency took their toll on Indigenous life.

Even many of the Indigenous groups that sought to continue their traditions were prevented from doing so—because they found themselves moved to reserves remote from their ancestral lands. And generations of Indigenous children were forcibly sent to church- and government-run residential schools, which systematically stripped away their culture and language. Even when these residential schools were shut down in the latter half of the twentieth century, the damage continued—for this policy of coerced assimilation left an Indigenous population that had greatly diminished first-hand knowledge of how to exist as mothers and fathers—which in turn has contributed to all manner of domestic tragedies in Indigenous communities.

White Canada responded, for the most part, by averting its eyes. A standard middle-school textbook published in 1957, We Live in Ontario, for instance, contained only a handful of scattered, en passant mentions of Indigenous peoples. (By way of comparison, sections on Mexico and Iceland each got about a dozen pages.) This was decades before the modern rise of today’s Internet-fueled Canadian Indigenous political renaissance. And many white Canadians simply assumed that First Nations communities eventually would melt into an increasingly prosperous, overwhelmingly white Canadian society.

When white Canadians did get the opportunity to educate themselves about the Indigenous world, it often was through journalism that treated these communities as exotic. A 1971 National Geographic cover story on the Inuit of Baffin Island, for instance, had the tone of an article written about Africa or Polynesia. Even so, the tone was sympathetic. The author, a French priest named Guy Mary-Rousselierre (1913-1994) who had lived in the area for a quarter century, related the good and the bad, without seeming hampered in any way by notions of political correctness.

In one memorable passage, for instance, a sled-trip companion confesses that he finds his igunak—summer-cured walrus meat prone to rot—to be utterly disgusting. Such a fact would be hard to include in a 2018-era magazine article, since the approved narrative now frowns on negative descriptions of traditional ways. While Canadian media outlets are encouraged to print and broadcast abundant material about Indigenous issues, editors are looking for retellings of the same approved bad-news/good-news story—according to which Indigenous communities apply courage and resilience to thwart the forces of white cultural genocide.

Another reason why such an article would be difficult to publish today is that Indigenous Canadian writers and broadcasters have been demanding the right to tell their own stories in their own voices. On university campuses, Indigenous experts have ensured that their history, culture and political demands be installed as part of the liberal arts curriculum. In Ottawa and provincial capitals, Indigenous groups such as the Assembly of First Nations have used modern lobbying and communications methods to get their message out—a phenomenon that received a signal-boost in the 2000s, when grass-roots activists started using Twitter and Facebook to mobilize. While the conditions on many reserves remain abysmal, these activists have at least succeeded in putting the demands of Indigenous communities front and centre on the Canadian political agenda. The age when callous whites could simply avert their eyes is thankfully over.

For Indigenous Canadians, this political awakening has been a welcome development. But it also has had a destabilizing effect on the self-conception of non-Indigenous Canadian society, which already was deep into the process of shedding its old-fashioned identity as a white, Christian nation. The introduction of Indigenous animist ritualism into Canadian public life over the last decade or so isn’t just an expression of “white guilt,” as many claim. It’s also part of a revival of Grey Owl-era reveries that, in turn, tap into romantic Canadian ideas about the frozen north.

All Western nations have witnessed a general casting about for something to replace religion as an organizing principle in the lives of ordinary people. But Canadians have experienced this phenomenon in an especially acute manner, because two other organizing principles of our national intellectual life—anti-Americanism and regionalism (especially the Quebec separatist movement)—also have fallen away during the same period. While many recent immigrants to Canada still enjoy a vibrant civic culture within their communities, old-stock WASPs inhabit an increasingly denuded spiritual milieu. Indigenous land acknowledgments and other secularized expressions of white original sin now provide the only thin tissue of public ritual they regularly experience.

I am not speaking figuratively here, for it has become genuinely fashionable for educated Canadians to speak of First Nations people as embodying quasi-mystical, even magical, properties. This helps explain why even avowed secularists, who would be disgusted to see a priest or minister preside at a public event, will adopt a solemn mien if a First Nations elder holds forth on the four sacred directions. When I read social-media accounts from my friends who have had encounters with Indigenous elders, they often reflect what Victor Watts called the sacred dialogue, “in which the author describes how some divine spirit or power, at first unknown to him, appears and reveals to him some portion of hidden wisdom.”

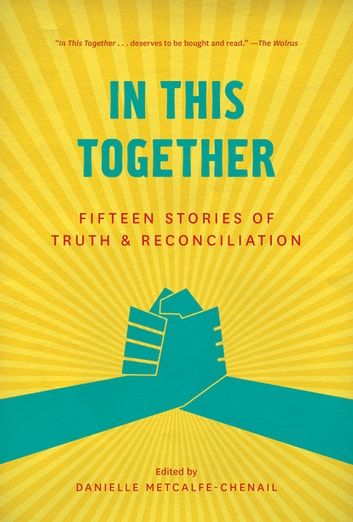

A best-selling collection of essays published in 2016—In This Together: Fifteen Stories Of Truth and Reconciliation—illustrates the trend well. In a piece titles Dropped, Not Thrown, non-Indigenous artist Joanna Streetly describes moving to Tofino, BC, at age 19, and falling in love with a Tla-o-qui-aht canoe carver: “Night after night I lay awake, examining the slant of my partner’s cheekbones and the heaviness of his long black hair…I wondered who I was and how we had come to be together. I dreamed vividly about whales and water and other worlds. I became untethered from my own self, immersed in a new universe.” Later on, Streetly describes reading a book about Australian aborigines, “for whom the world is not alive until they have walked through time—along dream tracks dating back to creation … I identified with the aborigines. I, too, was awakening to a new world, its features coming alive for me as I did so.” She represents her experience among Indigenous people as a process of salvation and “baptism.”

In other words, a full-bore spiritual awakening. As I wrote in a 2017 review of In This Together (from which I borrow liberally in the paragraphs that follow), traditional Indigenous lands exist in the imagination of these authors as places of magic and wonder—a sort of Narnia to which white people can escape when they tire of their own drab existence.

In an essay entitled Two-Step, non-Indigenous author Katherin Edwards appreciatively profiles Carol, an angelic First Nations restaurant owner in Kamloops, B.C. who serves up food with “love, affection, and good will”—even if white people are too callous to appreciate her labours. “I can always tell when [a food] order comes back,” Carol says. “If it’s First Nations [customers], then they take what they are given knowing we give our best. A Caucasian tends to say, ‘I want it done this way, with that’ ” Edwards assents to Carol’s surprisingly crude racial categorization. Indeed, she presents it as a microcosm of a broader, race-based moral hierarchy:

‘Then we’re still demanding,’ I say…. We have claimed the land and her resources. Foisted our culture on others. Bulldozed with our ideas to create our ideal and even here, even in this restaurant owned by First Nations, the insistence on having it our way hasn’t stopped. As Carol and her mother-in-law have held out their hands in an offer of sharing, I feel grateful but inadequate to give back.

By the end of the story, Edwards surrenders to the idea that no effort to expunge her race’s shame and guilt could ever feel sufficient—a frame of mind that Medieval monks once described as the living “bath of hell.” Author Donna Kane, similarly, reminded me of Lady Macbeth, pleading “Out, damn’d spot!” as she promises readers to “work on my reconciliation for the rest of my life.”

In describing the stock “Magical Negro” who often appears in popular books and movies, Nnedi Okorafor-Mbachu once noted that this type of character typically is shown to be “wise, patient, and spiritually in touch, [c]loser to the earth.” (Think of Morgan Freeman’s portrayal of Ellis Boyd “Red” Redding in The Shawshank Redemption.) In This Together contains a menagerie of similarly magical-seeming Aboriginals who are “soft-spoken” and “insightful.” A typical supporting character is the hard-luck Aboriginal child whose “entire face seemed to radiate a quiet knowing.” Older characters speak in Yoda-like snippets such as “There is much loss—but all is not lost.”

* * *

The Europeans who arrived in what is now called the Americas often treated the Indigenous population with brutality and contempt. It wasn’t until the last third of the twentieth century that anything resembling an enlightened attitude began to prevail in Canada. And it wasn’t until 1996 that the last residential school finally closed its doors. There can never be any excuse for the practice of forcibly removing children from their parents. The psychic wounds have reverberated through the generations, and the need for greater efforts to help Indigenous communities is real. No humane or reasonable person would deny this. As In This Together contributing author Steven Cooper aptly put it:

Most of the residential school attendees has their internal ‘Indian’ or ‘Inuk’ killed. The problem is that … the policy ended there. No one asked what would replace the parts killed, or who those children were to become as adults…. They grew up as hollow shells that turned to alcoholism, drug abuse and criminal activity. They repeated the abuses they endured.

But to read books such as In This Together is to understand that Canada’s intellectual class has overshot the mark in its bid to make amends. It is entirely true that the Indigenous societies of North America were rooted in economic and cultural traditions vastly different from those of the European explorers and settlers who invaded this continent. But it is absurd, and even regressive, to present whole swathes of humanity as inherently benign, or to turn pre-contact North America into a secular Eden. People are people. They come in good and bad flavours, no matter where in the world you go.

In large part, our historical double-standard arises from the fact that Indigenous societies typically had oral cultures, so there are few written sources to document the true fabric of their ancient life. The history of European and Middle-Eastern peoples, on the other hand, is recorded in written histories that clearly show the past to be a long series of wars, slaughters, famines, and epidemics. We can choose to believe Grey Owl-style fables about the one, but not about the other.

The construct of Indigenous people as sacred creatures is now being embedded into official government documents. An Interim Report published in 2017 by a Canadian Inquiry mandated to investigate the scandalously high rates of violent death among Indigenous women and girls, for instance, was titled Our Women And Girls Are Sacred. The authors tell Canadians that “Indigenous women and girls bring many gifts to the conversation on resilience, resurgence, and reconciliation. Some women are Grandmothers and Elders who carry sacred stories, laws, and ceremonies for future generations. Others are warriors who continue to speak for the silenced. Some are healers who draw on their own spiritual traditions, knowledge, and medicines to help those who are hurting.” Beautiful, soaring words—but also tinged with a spiritualism that is alien to the project of neutral fact-finding one expects from a government-mandated inquiry into serious crimes.

Many of the broad patterns of thought that I describe here apply as much to the United States as to Canada. But the particular geography of Canada makes our situation special. In the continental 48 states, all major Indigenous communities can be accessed by road, and tend to be at least somewhat integrated into local economies. In the Canadian north, by contrast, many reserves are isolated fly-in hamlets that still preserve their air of tragic exoticism. And so the racist legacy of Grey Owl becomes that much harder to extirpate.

Moreover, the commanding heights of Canadian arts and letters is still controlled by old-school white Torontonians who cling to the idea of the Arctic (and the north in general) as somehow comprising the frozen soul of a mythical, “true” Canadian identity. To this day, this is the part of the country where wealthy Canadians of a certain vintage go for expensive fishing and hunting expeditions. Or to attend high-end writers’ retreats or detox. While this cult of the north is of little interest to modern immigrants (as a second-generation Jew, I find it utterly baffling), it remains stubbornly influential. And it helps explain the lingering appeal of artists such as Lawren Harris, whose paintings portrayed northern mountainous sunscapes in much the same way as a small child would imagine God staring down at her from the clouds. In this conception, the north is Canada’s Holy Place. And Indigenous peoples are its racially defined priestly class.

And since white Canadians are now encouraged to imagine Indigenous biology as a DNA-encoded marker of exalted consciousness, many of the most bitterly contested debates in arts and letters now centre on allegations that this sacred way of knowing is being despoiled through the heresy of cultural appropriation. In one notorious case that I recently described for Quillette readers, for instance, a white novelist was attacked by Indigenous groups—with the support of the white literary press—for including a First Nations character in her novel; despite the fact that the author had hired an Indigenous consultant to examine her manuscript, and had even appeared before a council of Indigenous elders to answer questions about her artistic choices.

To call this “reverse racism” is misleading—as the word “racism” more commonly is used to describe the denigration of disadvantaged groups within society. And the novelist in question certainly would never claim to be a member of such a group. Moreover, hard-core racists typically appeal to pseudoscience to justify their bigotry, while the cult of Indigeneity being promoted by white Canadians is effectively a spiritual phenomenon. Nevertheless, the whole apparatus of Canadian culture, academia, and activism now operates according to an explicitly race-conscious moral hierarchy that draws heavily on the idea of white skin as a badge of guilt and shame. And much of the Canadian Left now organizes its cadres according to the logic of separate-but-unequal. One “Bill of Responsibilities” for white people who seek to help Indigenous causes, for instance, instructs non-Indigenous people to constantly “reflect on and embrace their ignorance of the group’s oppression and always hold this ignorance in the forefront of their minds.”

* * *

I will admit that there is a personal dimension to all this. I grew up in a Jewish household. But early in life, I turned my back on the ritual and theological aspects of Judaism, and began worshipping at the altar of science and free inquiry. And I always was happy and proud to live in a secular country where this sort of godless outlook was permitted, and even encouraged.

But scenes like the one I described at the beginning of this essay suggest that this is changing: religious attitudes are now creeping back into public life through a back door. And it is spreading fast. At some Canadian universities, professors now are required to print Indigenous land acknowledgments on their course syllabi. These acknowledgments also are recited every day at my children’s school—the equivalent of the Lord’s Prayer that I was required to recite before eating lunch at an old-fashioned Montreal boy’s academy in the 1980s.

“So what?” some may say. Great historical crimes have been visited upon this continent’s Indigenous peoples. And so the least that can be expected of a cranky middle-aged white culture critic and his family is to acknowledge the settler sins of the past and the enduring suffering of surviving Indigenous peoples. This, in so many words, is the answer one gets on social media, or in Canadian academic circles, when any of these points get discussed.

My answer to this is that Indigenous people themselves are being made to suffer for white spiritual conceits, because the miasma of guilt and self-censorship that now afflicts politicians and intellectuals is choking off important discussions that Indigenous peoples recognize as necessary to improve their communities.

I will not dwell too much in this space on the cruel, cynical, and utterly disastrous government decisions that have led to the current state of affairs in Indigenous communities. But perhaps the single largest enduring difficulty originates in the fact that land on Indigenous reserves is not owned by residents in their capacity as individuals. Rather, it is controlled collectively, so that no person or family can buy, sell, lease, or mortgage their property in the normal manner that the rest of us take for granted.

This has had a crushing effect on business formation and land improvement. And it is one of the reasons why the housing stock on reserves degrades so quickly: Since no one owns their house in the normal way, there is little financial incentive to invest in any even basic upkeep activities such as mould eradication. And since residents can’t mortgage their homes, no one has any basis for secured lending. Indigenous people are no less industrious and ambitious than anyone else in Canada, but they often must leave their reserve communities to find their fortune. To remain on reserve is, in many ways, to exist as a serf within a welfare state.

The question of how to resolve this difficulty obviously does not fall to me: It is something that Indigenous communities must determine themselves. And it’s a wrenching issue—because a capitalist-style land-ownership system would allow non-Indigenous outsiders to buy these communities out, thus undermining the goal of preserving and rekindling an authentic Indigenous culture. In some cases, both economic and cultural goals can be achieved through economic development in neighbouring areas and the devolution of more powers to band councils. But in other communities—especially those in remote areas, far from urban job centres—there will be wrenching choices to be made, pitting jobs against culture.

To repeat: the people who should be making these decisions are the members of Indigenous communities. But the process is skewed—because the modern white fetish for noble-savage mythology means that my country’s leaders now are effectively putting their thumbs down on the side of cultural preservation over economic development—since it is the spiritual side of Indigenous life that is the real subject of their fascination.

Indeed, in public discussions, questions of policy often get swept away under the utopian conceit that all will be remedied once Indigenous societies have the power to reinstate their ancient values within their respective communities—much as Christian, Jewish, and Islamic theocrats imagine that mundane matters of policy will be easily resolved once governance is given over to those who obey the tenets of their faith.

Surviving historical records show Indigenous peoples to be skilled negotiators, courageous warriors, and tireless hunters. Yet in the white imagination, these societies are imagined to have been proto-socialists, forever composing wise adages about the cycles of nature. Indeed, in British Columbia, the efforts of white environmentalists to cynically co-opt the mantle of Indigenous protector has been so brazen that some business-focused Indigenous groups now are rebuking them publicly.

Or consider the uproar that followed a 2017 Supreme Court of Canada decision, in which the Justices unanimously ruled against a First Nations band—the Ktunaxa—which opposed the creation of a ski resort on a mountain in British Columbia that, they claimed, was inhabited by a sacred Grizzly Spirit Bear. “Freedom of religion is supposed to provide equal protection for all religions,” wrote a pair of op-ed writers in The Toronto Star, Canada’s largest-circulation newspaper. “The Supreme Court’s judgment disadvantages Indigenous spiritual traditions, whose objects of reverence are connected to pieces of land vulnerable to physical destruction. The judgment shows how Eurocentric ideas about religion enable the continuing appropriation of Indigenous lands.”

And yet, amid such outrage, virtually none of these writers took note of the fact that a separate Indigenous group—the Shuswap, whose lands lie closer to the proposed ski resort than those of the Ktunaxa—actually supported the ski-resort project because of the jobs and economic benefits it would bring to the region. This is because the Shuswap took what non-Indigenous Canadians regard as an incorrect Indigenous position. In Toronto’s Globe & Mail, for instance, an article that notes that “the Shuswap accepted the [ski resort] proposal, saying the resort would benefit their community” was entitled “Top court deals blow to Indigenous peoples.” By “Indigenous peoples,” this headline writer meant “real Indigenous peoples”—as imagined from the downtown offices of Toronto’s (largely white) press corps.

One of the most brilliant Indigenous artists that Canada has produced is Tomson Highway, an award-winning Cree playwright and novelist who spent nine years at a residential school in Ontario. In early 2015, I commissioned a piece from Highway for a magazine I then edited, in anticipation of the release of a major report on the residential-school legacy. Highway’s submission was brilliantly crafted. It was heretical, too: While acknowledging the terrible effects of residential schools on many Indigenous children, he also credited this education for some of the skills that allowed him to become a renowned artist.

And that’s why the piece was never published. One of my colleagues—a man whiter than me (if such a thing were possible) informed me that the piece would be “problematic” because it would hurt the “relationships” our magazine had created. When I probed further, it was made clear to me that the sensitive constituencies in question included not only Indigenous groups, but also non-Indigenous groups (and donors) that had come to see our magazine as a reliable voice for the approved position on this issue. Which meant we couldn’t just champion the voices of Indigenous peoples—we have to champion the right kind of Indigenous peoples. This sort of surreal and cynical conversation goes on, in hushed tones, all across the Canadian journalistic and academic landscape.

It was one of those moments when I realized that what I had entered was not a journalistic enterprise, but a sort of congregation. And it was only after I left it that I was free to think and pray as I wished. This included the freedom to not pray at all—as is my preference—even when instructed to do so by a kindly old lady.

The ground is not sacred to me. It is a spinning orb of rock that was created by physical forces well understood by scientists. When Indigenous people ask my government to share the Canadian portion of that rock on fair terms, and to make good on old promises, I very much applaud. But let us keep our white spiritual appetites out of the conversation. Indigenous peoples should not suffer another lost generation so that white Canadians can touch the face of someone else’s god.