Art and Culture

Becoming a Man

“To be a man in most of the societies we have looked at, one must impregnate women, protect dependents from danger, and provision kith and kin.”

“In the puberty rites, the novices are made aware of the sacred value of food and assume the adult condition; that is, they no longer depend on their mothers and on the labor of others for nourishment. Initiation, then, is equivalent to a revelation of the sacred, of death, sexuality, and the struggle for food. Only after having acquired these dimensions of human existence does one become truly a man.” – Mircea Eliade, Rites and Symbols of Initiation: The Mysteries of Birth and Rebirth, 1958

“To be a man in most of the societies we have looked at, one must impregnate women, protect dependents from danger, and provision kith and kin.” – David D. Gilmore, Manhood in the Making, 1990

“Keep your head clear and know how to suffer like a man.” – Ernest Hemingway, The Old Man and the Sea, 1952

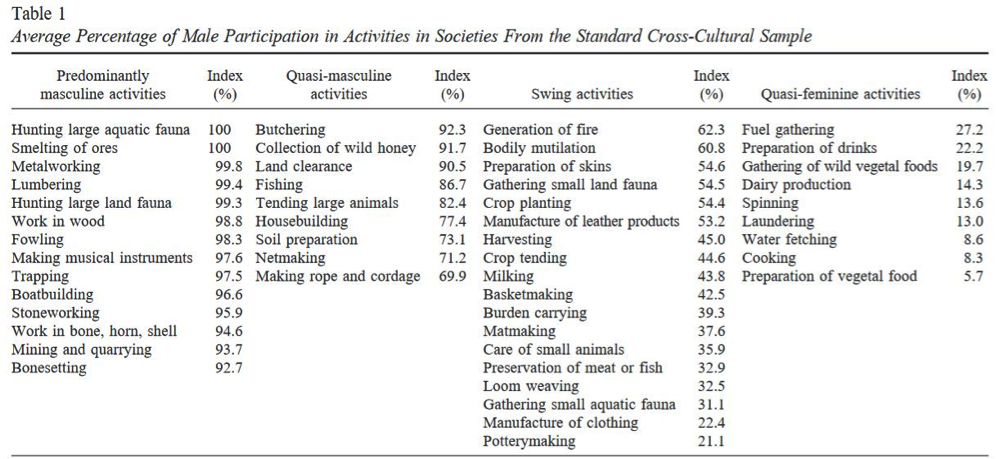

There are commonalities of human behavior that extend beyond any geographic or cultural boundary. Every known society has a sexual division of labor – many facets of which are ubiquitous the world over. Some activities are universally considered to be primarily, or exclusively, the responsibility of men, such as hunting large mammals, metalworking, and warfare. Other activities, such as caregiving, cooking, and preparing vegetable foods, are nearly always considered primarily the responsibility of women.

In my last article for Quillette, I noted that in every known society males are more likely to kill another person than females are, and that this pattern is ultimately fairly predictable in light of some basic sex differences in reproductive biology. Here, I want to explore the functions of socialization, and ideology, as they contribute to the differing sex roles of males and females across cultures. In particular – how boys become men, and what the social demands of masculinity often entail.

The recognition that hunting is a predominately male behavior is widespread across cultures. In fact, this association is not unique to humans. In the volume Chimpanzees and Human Evolution (2017), anthropologists Brian Wood and Ian Gilby write that, “Among all primates that regularly hunt vertebrates, including chimpanzees, baboons, and capuchins, males hunt more frequently than females.” Yet hunting among human populations is not solely an extension of a biological inclination found predominately among males; it is a behavior that is often deeply infused with social meaning.

The hunt is central to masculine identity among many hunter-gatherer populations, such as the !Kung of the Kalahari Desert. In her book on Nyae Nyae !Kung Beliefs and Rites (1999), anthropologist Lorna Marshall wrote that, “With the rarest exceptions, all !Kung men hunt. Little boys play with tiny bows and arrows from the time they can walk and practice shooting throughout their childhood. At adolescence, they begin to hunt with their fathers.” The practice of learning to hunt is part of a boy’s transition to manhood, and it holds strong ritual significance. Marshall notes that, “The most important rite in a !Kung boy’s life is the Rite of First Kill,” and she further describes its role in the !Kung social system;

A boy may not marry until he has killed a big meat animal and had the rite performed. The rite marks the change of state from boyhood to that of hunter, which in !Kung culture is equated with manhood…The principal element in the rite is the scarification of the boy. The purpose of this is to put into the boy’s body, through little cuts in his skin, substances that, in !Kung belief, will make him a successful hunter. The scarifications remain visible on the skin for a lifetime; they show that the man has been “cut with meat.” (Marshall, 154)

An emphasis on the essential role of hunting – and male provisioning more generally – in marriage practices is quite common. Anthropologist Lewis Henry Morgan described the Iroquois tradition of exchanging food to ratify a marriage; the bride would present cornbread to her mother-in-law indicating “her skill in the domestic arts”, and in turn “a present of venison, or other fruit of the chase,” would be given to her own mother, indicating her future husband’s “ability to provide for his household.”

Anthropologist Frank Marlowe found that among Hadza hunter-gatherers, it is the women who bring more food back to camp, on average, than the men do. Yet this is driven in part by lackluster returns from unmarried men, who often eat while out foraging, bringing less food back to share. It is married men with young children who bring the most food back to camp, providing essential calories for their family. The demands of family life can offer a powerful inducement for male responsibility.

Success in hunting is often an explicit pathway to increased prestige. Commonly across cultures, better hunters have better reproductive success, and are usually conferred high-status. In Cultural Anthropology: Tribes, States, and the Global System (2011), anthropologist John Bodley writes that, “Throughout Amazonia, hunting success is equated with virility, and the successful hunter can support extra wives and lovers through gifts of meat.”

Across small-scale societies, hunting is a valuable, highly practical skill, allowing the attainment of nutrient dense foods to provide for one’s family, while also acting as an appealing signal to the rest of the social group, indicating a man’s competence and expertise at a difficult task.

Teaching socially valued skills, such as hunting, and instilling courage and a tolerance for pain that might be required for success in warfare, are often part of masculine rituals and rites of passage. In the volume Rituals of Manhood (1982), anthropologist Gilbert Herdt noted that, throughout New Guinea, “the rites of making men…share in common the intentionality of instilling warriorhood, masculine identity, and higher social status in the change from boyhood to manhood,” and we see “similar transitions to adult manliness in many social formations—ancient and modern, across civilizations large and small—around the world.”

The world over, there is a sense that manhood is precarious; that it is something that must be earned over time, yet can quickly be taken away.

One manner in which men are considered to be stripped of their masculinity is through being subdued in war. In 1754, as recounted by diplomat Conrad Weiser, Chief Tamaqua of the Delaware Tribe addressed the Six Nations of the Iroquois, describing their past battles in war, saying, “I still remember the Time when You first conquered Us and made Women of Us, and told Us that You took Us under your Protection, and that We must not meddle with Wars, but stay in the House and mind Council Affairs.”

According to a member of the Seneca tribe, known in English as Captain Newcastle, in 1756 the Mohawk chief, Canyase, said, “We, the Mohwaks, are men; we are made so from above. But the Delawares are women and under our protection, and of too low a kind to be men…”

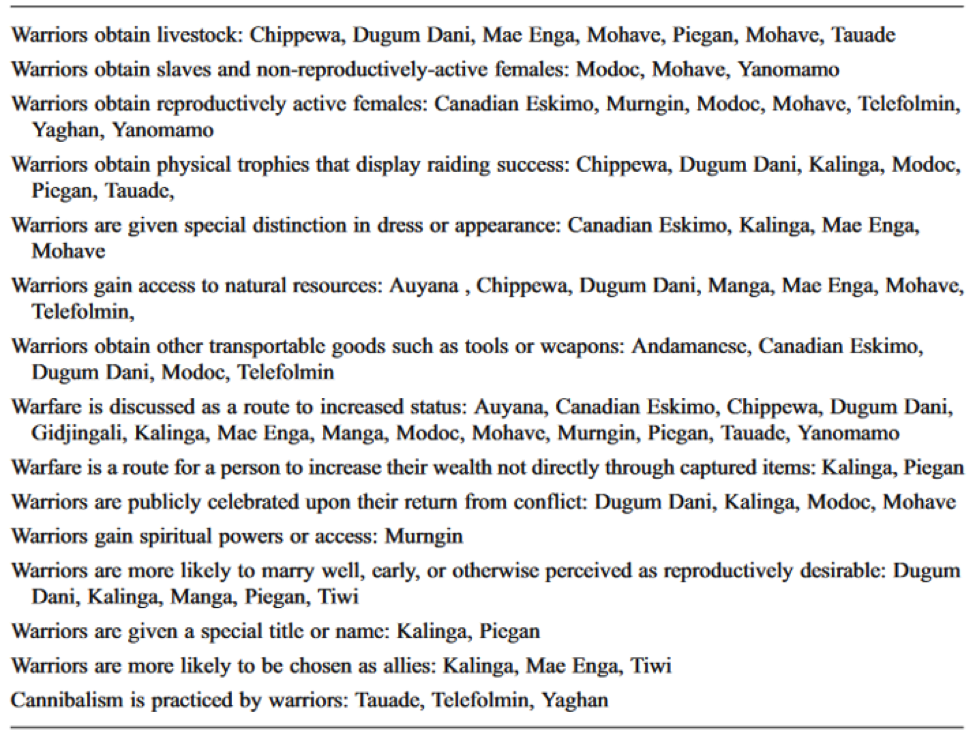

Conversely, success in warfare has often conferred important social benefits for males, such as increased status, access to resources, and better marriage opportunities. In his book Cattle Brings Us To Our Enemies (2010) about Turkana pastoralists, anthropologist J. Terence McCabe writes that, “Young women will sing songs about young men who are successful raiders, and such individuals often receive the benefits of their adulation.”

Warfare also creates the need for effective leaders that can build and maintain strong coalitions. In the volume Manhood in the Making (1990), anthropologist David D. Gilmore, describing the importance of leaders among various New Guinea societies, writes, “Through this hands-on leadership, the Big Man does something more than fight, fend off enemies, and exemplify a warrior ideal for impressionable boys and aspiring youth; he establishes an artificial social cohesion for the people of his village or territorial unit.”

Across vastly different societies, with very dissimilar political systems, it is often similar sets of skills that are considered desirable for their (predominately male) leaders. A man can gain status through displays of key talents; through his ability to persuade; by developing and maintaining important social relationships; and by solving difficult problems. In his classic paper on the political systems of ‘egalitarian’ small-scale societies, anthropologist Christopher Boehm writes, “a good leader seems to be generous, brave in combat, wise in making subsistence or military decisions, apt at resolving intragroup conflicts, a good speaker, fair, impartial, tactful, reliable, and morally upright.” In his study on the Mardu hunter-gatherers of Australia, anthropologist Robert Tonkinson wrote that the highest status was given to the “cooks,” which is the title given to “the older men who prepare the many different ceremonial feasts, act as advisors and directors of most rituals (and perform the most important “big” dances), and are guardians of the caches of sacred objects.”

Anthropologist Paul Roscoe writes that some of the important skills of ‘Big Men’ in New Guinea horticulturist societies are, “courage and proficiency in war or hunting; talented oratory; ability in mediation and organization; a gift for singing, dancing, wood carving, and/or graphic artistry; the ability to transact pigs and wealth; ritual expertise; and so on.” In the volume Cooperation and Collective Action (2012), Roscoe notes further that the traits that distinguish a ‘Big Man’ are “his skills in…conflict resolution; his charisma, diplomacy, ability to plan, industriousness, and intelligence” and “his abilities in political manipulation.” In their paper on ‘The Big Man Mechanism,’ anthropologist Joseph Henrich and his colleagues describe the common pathways to status found across cultures, noting that, “In small-scale societies, the domains associated with prestige include hunting, oratory, shamanic knowledge and combat.”

A similar process can be seen at work even in contemporary, large-scale, democratic societies. In an article about French President Emmanuel Macron over at the Wall Street Journal, journalists Stacy Meichtry and William Horobin write, “Mr. Macron made friends in high places who propelled him to ever-higher echelons of French society. Along the way he acquired a repertoire of skills, from piano and philosophy to acting and finance, that helped impress future mentors.” Displaying visible skills, demonstrating possession of relevant knowledge, and managing personal relationships are key factors in obtaining status.

Essential to the ideal conception of masculine identity is exhibiting competence in socially valued domains, while taking on important responsibilities and offering leadership.

When looking across cultures at ideological conceptions of manhood, we see many of the same themes occurring continuously. In the book Law and Order in Anglo-Saxon England (2017), historian Tom Lambert analyzes King Æthelberht’s code of law in the Kingdom of Kent in 6th century CE, and describes what the laws conveyed about masculine social identity in this society. Lambert notes that, “Virtually every clause of the code is concerned to define an affront and the compensation appropriate to it.” One extended passage in particular is worth quoting in full. Lambert writes;

Within this model of an ideal society of free males is a model of an ideal free man. He is strong and determined, in that he is willing and able do what is necessary to maintain his honour, insisting on being compensated in full for any affront. However, he is also level-headed and reasonable: his strength and determination are used to exact the compensation required to maintain his honour, and no more. He does not rush precipitately to avenge wrongs done to him, nor does he take advantage of his strength to dishonour his opponents by extorting more from them than is just. And he is careful not to impose obligations on others. He accepts full responsibility for all his own actions, personally paying compensation when it is right to do so, and he is certainly not so hot-headed and self-indulgent as to engage in reckless acts which might compel his family to use their wealth to bail him out. A proper man, the laws imply, is not just strong and determined, he exercises restraint because of his commitment to the ideal of a community of free men who respect one another’s honour. The laws thus promote a particular construction of masculinity, one distinctly tinged by social responsibility. (Lambert, 57)

This conception of a socially responsible sense of masculinity may offer some lessons for men of our own era.

In his book How Can I Get Through To You? (2002), author Terrence Real describes visiting a remote village of Maasai pastoralists in Tanzania. Real asked the village elders (all male) what makes a good warrior and a good man. After a vibrant discussion, one of the oldest males stood up and told Real;

I refuse to tell you what makes a good morani [warrior]. But I will tell you what makes a great morani. When the moment calls for fierceness a good morani is very ferocious. And when the moment calls for kindness, a good morani is utterly tender. Now, what makes a great morani is knowing which moment is which! (Real, 64)

This quote is also favorably cited by feminist author bell hooks in her book The Will to Change (2004). While hooks and Real offer perspectives quite different from my approach here, the words of the Massai elder illustrate an ideal conception of masculinity that may appeal to many people of diverse ideologies and cultural backgrounds. A great warrior, a great man, is discerning – not needlessly hostile nor chronically deferential, he instead recognizes the responsibilities of both defending, and caring for, his friends and family.

In The Cassowary’s Revenge (1997), anthropologist Donald Tuzin discusses his fieldwork among the Ilahita Arapesh horticulturalists of New Guinea, and describes a man who seems to fit many facets of this masculine ideal;

Kwamwi, for example, was not only of the highest ritual rank, he performed as a master artist and one of the village’s leading shamans. In the opinion of neighboring enemy villages, Kwamwi was a dangerous sorcerer, a cold-blooded killer who fueled his mystical power by eating human corpses. Taking pains to look like a man of parts he was always decked out in shell jewelry and a jaunty comb-and-feather arrangement in his hair. Around his neck hung an unadorned little bundle, containing, he said, the magically efficacious finger of a bush demon he had once killed in the jungle. Although Kwamwi could be scary when it suited him and could more than hold his own as a magician, artist, and orator, off-stage he was remarkably sweet tempered and playful. Little children adored him; he was a gentle husband; and, to my knowledge, he was the only man in the village at the time who treated his dog with kindness, and who gave it a name – Kailal. (Tuzin, 28)

Finally, we come to the central question: why are these particular conceptions of masculinity so common across cultures and throughout history, and what are the implications for our current, democratic, post-industrial era?

Terrence Real and bell hooks, like many other feminist writers, are very critical of phrases such as “be a man” or “man up,” arguing that these sort of statements impose rigid gender norms and unreasonable standards on young boys. I’d like to propose an explanation for why these kinds of comments exist in the first place.

As anthropologist David G. Gilmore notes in Manhood in the Making, exhortations such as “be a man” are common across societies throughout the world. Such remarks represent the recognition that being a man came with a set of duties and responsibilities. If men failed to stay cool under pressure in the midst of hunting or warfare, and thus failed to provide for, or protect, their families and allies, this would have been devastating to their societies.

Throughout our evolutionary history, the cultures that had a sexual division of labor, and socialized males to help provide for and protect the group, would have had a better chance at survival, and would have outcompeted those societies that failed to instill such values.

Some would argue, quite reasonably, that in contemporary, industrialized, democratic societies, values associated with hunting and warfare are outmoded. Gilmore writes that, “So long as there are battles to be fought, wars to be won, heights to be scaled, hard work to be done, some of us will have to “act like men.”” Yet the challenges of modern societies for most people are often very different from those that occurred throughout much of our history.

Still, some common components of the traditional, idealized masculine identity I describe here may continue to be useful in the modern era, such as providing essential resources for the next generation of children, solving social conflicts, cultivating useful, practical skills, and obtaining socially valuable knowledge. Obviously, these traits are not, and need not be, restricted to men. But when it comes to teaching the next generation of young males what socially responsible masculinity looks like, it might be worth keeping these historical contributions in mind. Not as a standard that one should necessarily feel unduly pressured by, but as a set of productive goals and aspirations that can aid in personal development and social enrichment.