Top Stories

Fundamentalists vs The New York Times

Leftists believe liberalism is a spineless doctrine of compromise and accommodation, and that the only useful response to right-wing populism is a left-wing variant that is just as trenchant, intolerant, illiberal, and doctrinaire.

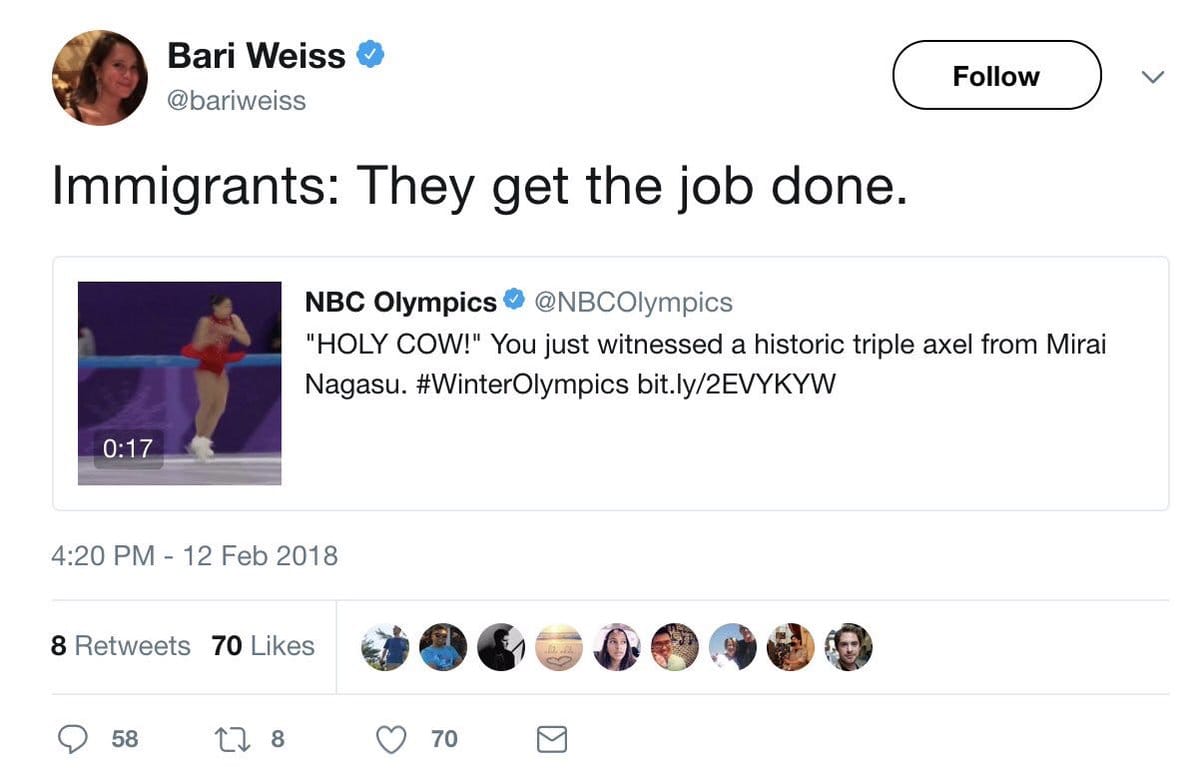

Last week, Bari Weiss, a staff editor and columnist for the opinion pages of the New York Times, became the latest person to find herself at the centre of a social media feeding frenzy for sending a carelessly worded tweet. Even that summary doesn’t do justice to the inanity of the controversy, since “carelessly worded” concedes more to her critics than their bad faith deserves. On 12 February, upon learning that US figure skater Mirai Nagasu had successfully performed a triple axel at the Winter Olympics, Weiss shared an NBC video of Nagasu’s spectacular achievement along with the comment, “Immigrants: They get the job done.” Her tweet was a reference to a line from the Hamilton musical—later turned into a song for The Hamilton Mixtape—celebrating the contribution immigrants have made to America (sample lyric: “Who these fugees? What did they do for me?/But contribute new dreams/Taxes and tools, swagger and food to eat…”).

It ought to have been obvious to all but the most stubbornly obtuse that Weiss was using Nagasu’s accomplishment to salute the part played by immigrants in America’s successes, and that she did so to signal her explicit disapproval of xenophobic politics. A backlash might therefore have been expected from the retrogressive Right, but it came instead from the retrogressive Left. Nagasu, Weiss’s critics complained, had been born in California to immigrant parents, so describing her as an “immigrant” is evidence of racism. As condescension and abuse piled up in her mentions, Weiss deleted the tweet but her refusal to apologise only sent her critics into new paroxysms of high dudgeon.

If the proximate cause of all the outrage was a politically inexact tweet, an ultimate cause soon became apparent as the row developed and attention turned to the editorial policy of the New York Times since the presidential election. Criticism of Weiss’s tweet grew to encompass her views on unrelated topics, and articles that she (and even members of her family) had written for the Wall Street Journal were circulated on social media as further evidence of her political transgressions: Bari Weiss is too pro-Israel; she is too close to the neoconservatives; she had defended Aziz Ansari from his accusers; and she had denounced the excesses of the #MeToo movement on Bill Maher’s Real Time just three days before the Twitter storm erupted.

So what, Weiss’s opponents were now demanding to know, is this terrible person doing at the New York Times? And what, by the way, is Weiss’s former WSJ colleague Bret Stephens still doing there? And what is the New York Times doing hiring journalists away from the conservative Journal anyway? The Times already publishes the conservative opinions of Ross Douthat and David Brooks—are its readers not suffering enough? And why had Douthat been allowed to publish a column entitled “The Necessity of Stephen Miller”? And hadn’t the Times run a suspiciously sympathetic profile of a white nationalist back in November?

Mutiny stirred even within the New York Times itself, and as their embattled colleague tried to defend herself on social media, Times employees took to the Slack chatroom to bellyache about “microagressions,” the merits of mandatory “implicit bias training,” and the “hostile work environment” allegedly produced by Weiss’s innocuous tweet. The stupefying exchange was then leaked to a rival publication and reproduced with the names redacted beneath the byline of a former Gawker journalist.

The @nytimes seems like a nice place to workhttps://t.co/hHTYrObzAS

— Brent Scher (@BrentScher) February 14, 2018

As if things weren’t already bad enough, the day after Bari Weiss sent her tweet, already febrile passions were further inflamed when the Times proudly announced it would be hiring Quinn Norton as a contributor. Evidently, the paper had decided to hire a tech columnist who could write knowledgeably about the murky world of internet subcultures in which Norton had spent considerable time. Less than seven hours later this decision had been reversed after the paper was made aware of her friendships with neo-Nazis and casual use of various slurs on social media. A new wave of outrage ensued, and blogs and articles began appearing which bracketed the Bari Weiss and Bret Stephens and Quinn Norton hires as part of the same post-Trump ‘problem’ at the New York Times. It is a problem for which these writers struggled to provide an adequate explanation.

Over at the Ringer, the inaptly named Justin Charity speculated that, “So transparent are Norton’s disqualifications that it’s tempting to believe the New York Times regarded them as qualifications.” But why is it tempting to believe that? A more reasonable and plausible explanation is that the hire was just a mortifying failure of due diligence. Once Norton’s tweet history and various other incriminating writings and remarks were brought to the paper’s attention, they fired her so fast that Charity admits to finding the spectacle “surreal.” I can find no reason why anyone at the Times would take a decision, an entirely foreseeable consequence of which would be sentences like this one from Charity: “Norton’s hiring proved scandalous because her public language was exceptionally foul, and her association with neo-Nazis is so plain and shameless.”

But Charity insisted that Norton’s hire is part of a pattern of malevolent behaviour which includes the hiring of Stephens and Weiss, and which he claims has transformed the Times’s OpEd page into “the most influential gallery of bigots and dipshits in the history of Chartbeat.” He even pours scorn on the paper’s “obsessive dispatches from ‘Trump country,’” and argues that such articles are unlikely to be explained as attempts to appeal to Trump voters because “no earthly organism could be so misguided as to assume that any number of hateful gamers, stalwart birthers, and MAGA propagandists are in the market for a fact-driven newspaper.”

If Charity demonstrates an obdurate refusal to understand Trump voters or the Times’s attempt to explain them to its bewildered readership, it is because he has decided that neither deserve to be understood. The Ringer’s standfirst promises to explain the New York Times’s behaviour, but Charity’s article is so saturated in its author’s righteous contempt that charitable explanations are deemed unworthy of effort. Instead, Charity concludes that the paper’s “reactionary provocations” should be understood as the cynical peddling of controversy and contrarianism in pursuit of clicks:

In recent months, the judgment in various corridors of the New York Times building has proved so humiliating, so repeatedly, and so reliably, that it’s tempting to view all these supposed missteps as the deliberate editorial strategy indeed.

Indeed? Charity’s sour diatribe only makes me wonder why his temptations reliably lead him to ascribe such low motives to those with whom he disagrees.

Over at the Outline, meanwhile, former Gawker features editor Leah Finnegan offered her take on what she called “The Bari Weiss Problem.” The OpEd page at the Times, she explained, “is a troll factory” in search of site hits. “[T]he troll factory gets results,” she announced, “and the media isn’t really in a position to turn away readers. A Bari Weiss is great for the bottom line, actual politics be damned.” Those complaining about the vilification of Weiss on social media were engaging in what she called “Trumpian logic. Complainer says he should be free to complain because of free speech, but should he say something bad or wrong, no one can complain about what he said.”

In New York media, the dedicated columnists who investigate crimes against The Discourse are members of an elite squad known as the Always Victims Unit. These are their stories. DUN DUN. https://t.co/8mZrcd6A3t

— The Outline (@outline) February 14, 2018

But that is not the complaint at all. The complaint is that perfectly legitimate and, in Weiss’s case, even progressive opinions are being subjected to egregiously uncharitable misreadings for which they are then attacked. Finnegan chastises Weiss for failing to acknowledge that Mirai Nagasu “was born in California, making her not an immigrant, but an American on American soil” but she does not stop to consider the pettiness of this objection, or the triviality of Weiss’s error, given the tweet’s clear intention.

Finnegan’s casual misrepresentation of Bret Stephens in the same column is even worse. Stephens, she claims, had written that “Woody Allen wasn’t a bad guy because he maybe only molested his daughter one time.” What Stephens wrote was this:

Nor have we learned anything else about Allen in the intervening years that might add to suspicions of guilt. He married Soon-Yi and has been with her ever since. Nobody else has come forward in 25 years with a fresh accusation of assault against him. If Allen is in fact a pedophile, he appears to have acted on his evil fantasies exactly once. Compare that to Larry Nassar’s 265 identified victims.

Now, what is the more reasonable interpretation of this passage? That Allen only molested his daughter once and that Stephens finds this unworthy of concern, as Finnegan alleges? Or that the absence of further accusations makes the only accusation of which we are aware significantly less plausible? Of course, it is possible to disagree with the latter point of view, but it is necessary to understand it first. Finnegan and Charity clearly believe that Stephens’s defence of Allen ought to be disqualifying, and they expect their readers to agree without the need for elaboration. The accusations made by the Farrow family are in fact extremely dubious, but certainty regarding Allen’s guilt seems to have calcified into an article of faith among progressive millennials, in particular. To disagree is, by itself, enough to be considered morally and politically suspect.

Bari Weiss and and Bret Stephens both left the Wall Street Journal and joined the New York Times within a couple of days of each other last April. As the Journal shifted its editorial line in a more Trump-sympathetic direction after the election, the position of anti-Trump columnists began to look untenable. Stephens and Weiss had both voted for Clinton, so the joint move to the Trump-unsympathetic Times should not have been such a surprise. But Stephens is a conservative Republican and Weiss is a liberal Democrat, which is probably why he bore the brunt of readers’ outrage at the time. In a pre-run of the storm that would later engulf Weiss, progressive bloggers and commentators dug up articles Stephens had written for the Journal on climate change, the Black Lives Matter movement, campus sexual assault, Arab anti-Semitism, and hunger, and declared his opinions on every one of these subjects to be unacceptable. This task was made easier by a willingness to misrepresent his positions and to subject those he did hold to the most ungenerous interpretation available.

Stephens was not the first person to point out that, if the statistics routinely cited by anti-rape activists were accurate, levels of sexual violence on college campuses would be comparable to those found in the war zone of East Congo. Nevertheless, for Osita Nwanevu at Slate, Stephens’s use of this analogy was prima facie evidence of racism. “Leave aside, if you can,” Nwanevu wrote, “Stephen’s [sic] use of Africa as shorthand for sexual predation . . . he argues that the actual statistics marshalled by sexual assault advocates obviously aren’t to be trusted.” But as Nwanevu must have known, numerous journalists—liberal and conservative, male and female—had already drawn attention to the shabby methodology upon which these statistics relied. It was Emily Yoffe who had first made the comparison with Congo in a long essay about the campus rape panic for… Slate. And she had done so for the same reason—to expose the absurdity of the statistic Nwanevu was now defending.

Nwanevu and The New Republic’s Sarah Jones denounced Stephens for casting doubt on reports that one in seven Americans go hungry. Both writers linked to data they claimed proved that Stephens was whitewashing an ugly American reality. But as Cathy Young subsequently pointed out, anyone who bothered to follow the link Jones provided would have discovered that the one-in-seven figure refers to ‘food insecurity’ not hunger. “Stephens,” Young concluded tersely, “is not the one doing bad journalism.”

All of the accusations against Stephens fell apart once subjected to a moment’s critical scrutiny, but the prevailing mood amongst the readership and wider Left was one of denunciation not inquiry. Anguished Times readers, who might have simply ignored his articles and continued to enjoy the rest of the paper, instead advertised their cancelled subscriptions on social media as if they were burning draft cards. These were not acts of good faith disagreement, they were extravagant displays of conscientious objection, replete with much wailing and cloth rending and gnashing of teeth. For violating environmentalist taboos and articles of liberal political faith about campus sexual violence, Stephens was denounced as an interloper whose ideological toxicity threatened to taint the entire community unless he was expelled forthwith.

These were the days before Bari Weiss blithely informed Bill Maher that the social construction of gender is a myth and that persons accused of sexual assault are entitled to due process. So her own arrival at the Times passed with comparatively little comment. The Intercept’s Glenn Greenwald, however, found plenty of reasons to be object. In August of last year, he wrote one of his hectoring columns, which he recirculated in the hours after outrage about Weiss’s Olympic tweet went viral.

With characteristic perversity, Greenwald’s point of view put him at cross-purposes with almost all of the New York Times’s progressive critics. The problem with the Weiss and Stephens hires, he complained, was not that they challenged the prevailing consensus at the Times, but that they reinforced it. “For the contemporary NYT op-ed page,” he wrote, “diversity spans the small gap from establishment centrist Democrats to establishment centrist Republicans,” and “on the most contentious issues that divide the country, the range of opinion they offer is as narrow and stultifying as their demographic diversity is.”

Greenwald does not explain why such uncontroversial hires had managed to provoke so much controversy, or why the Times had been forced to defend viewpoint diversity if, as Greenwald claimed, there was no viewpoint diversity to defend. Nor does he acknowledge that all publications delimit the range of views they publish to some degree, including the Intercept. Greenwald might mock the “narrow and stultifying” Clintonite Zionist consensus that precludes the Times from regularly carrying the opinions of the Buchananite Right or the Chomskyite Left. But the Times has occasionally published propaganda screeds by members of the PLO and even Hamas officials, while the chances that the Intercept will ever publish a neoconservative like Stephens, or even a Zionist liberal like Weiss, are exactly nil (and I think Greenwald would agree).

Naturally, bad faith and intellectual dishonesty also inform Greenwald’s attacks on Weiss, for whom he has nothing but poly-adjectival disdain. Her writing consists only of “trite, shallow, cheap attacks” and “cheap, easy, and superficial ‘controversy.’” Guilt-by-association is first condemned (to exonerate Democratic congressman Keith Ellison and others on the Left who have praised conspiratorial racists like Louis Farrakhan) and then employed (to denounce Weiss and her neoconservative colleagues). For Greenwald, it is the campaign against Ellison that is “deceitful, repugnant, and yet quite predictable” and Weiss and her friends and associates who espouse “some of the most repugnant ideas to gain traction in U.S. discourse since the War on Terror began.” Commentary editor John Podhoretz, we learn, is “literally an advocate of genocide” for writing a column tentatively interrogating the disadvantages faced by law abiding liberal democracies engaged in asymmetric warfare.

What we have here is a failure to communicate, and it is wilful. In the populist lexicon, the term “neocon” does not denote a set of political positions with which Greenwald or the Times’s left-wing critics are prepared to disagree in good faith; it is simply an instrument of stigmatisation. Identifying political opponents as such is reason enough to expel them from the realm of legitimate discussion. And as the Left continues to divide against itself in the Trump era, heterodox opinions on a whole range of complex questions are being re-described as heresies so that the sphere of reasonable disagreement diminishes while the list of non-negotiable orthodoxies lengthens.

Invited to discuss the vilification of political scientist Charles Murray at Middlebury on Charlie Rose last year, the social psychologist Jonathan Haidt described the incident in explicitly religious terms. “The best way to understand what happened,” Haidt argued, “is an auto-da-fé—a religious rite.” That is why the protesters were so adamant that the event be moved off-campus, he explained: “The campus is like a church and you cannot have blasphemy on campus.” It wasn’t enough simply to express disagreement or disapproval. Murray’s mere presence was somehow so disruptive to moral order, it threatened to pollute the sanctity of the territory itself. This secular fanaticism is what lies behind the attempt to drive Bari Weiss and Bret Stephens from the masthead of the New York Times. That they are both immigration doves and ardent Trump opponents counts for nothing until and unless they are prepared to endorse every dot and comma of progressive dogma.

As Haidt has noted elsewhere, political purification and polarisation are the products of longstanding political trends. But they seem to be accelerating with alarming rapidity in response to our present moment. Liberals have responded to Trump, Brexit, and the transnational rise of the populist far-Right by worrying that the pragmatic centre is in danger of collapse and that now, more than ever, it is vital to defend democratic institutions, free speech, free assembly, and the rule of law. Leftists, meanwhile, see liberalism as a spineless doctrine of compromise and accommodation, and that the only useful response to right-wing populism is a radical left-wing alternative that is comparably trenchant, intolerant, illiberal, and doctrinaire.

A rallying cry published in the Guardian on 6 February of last year made this explicit. Bylined by six activists, one of whom is a convicted Palestinian terrorist and another of whom is an unrepentant Stalinist, the article called for a new global anti-capitalist feminist movement that would be “anti-racist, anti-imperialist, anti-heterosexist and anti-neoliberal.” Its authors announced that “it is not enough to oppose Trump and his aggressively misogynistic, homophobic, transphobic and racist policies. We also need to target the ongoing neoliberal attack on social provision and labor rights” as well as 30 years of “financialization and corporate globalization” and something called “corporate feminism.” With every subsequent line of the article, the circle of the indicted widens and the circle of available allies shrinks. On which subjects will reasonable people of goodwill still be permitted to disagree?

The same day that the Guardian published this quasi-manifesto, the neoconservative writer David Frum published a long article in the Atlantic entitled “What Effective Protest Could Look Like,” in which he sketched an alternative approach. Trump’s opponents on the Left and the Right, Frum wrote, needed to set aside political purity and to start thinking strategically. If Trump represents a unique threat to liberal democratic norms, constitutional protections, minorities and so forth, then his removal from office should be the sole focus of his opponents’ political activity. Neither the mass mobilisation of peaceful demonstrators nor riots on college campuses would achieve this end; the former is rarely politically effective, and the latter would be positively counter-productive. Instead, activists should identify a single issue on which Trump is vulnerable and then unite behind a straightforward demand, ideally one that can be met with the passage of legislation. As important, opponents of Trump on the Right and the Left must be willing to subordinate all other political disagreements in pursuit of this shared goal.

Frum’s article is lucid and convincing. Unfortunately, its observable impact has been zero. Trump’s enemies are more divided than ever. As I write, the Washington Post’s newest hire, Megan McArdle, is being subjected to the same dismal treatment as Bret Stephens. For Weiss’s puritanical critics, meanwhile, it seems that earnest expressions of support for immigrants and immigration are no better than unambiguous xenophobia if they fail to conform to every stipulation of progressive dogma. “Bari Weiss,” remarked one Twitter user in a rare perceptive thread amid all the furious din, “articulated a broadly accepted progressive belief—in the virtues of immigration, announcing her pride in an American athlete. But the priests of intersectionality chose to attack her for not doing it in the proper way.” This, he observed, “is a widespread and well-understood phenomenon…and the name of that phenomenon is fundamentalism.”