History

Why Walls Work

Walls are potent political issues today because citizens of afflicted nations are suffering real costs from illegal mass migration.

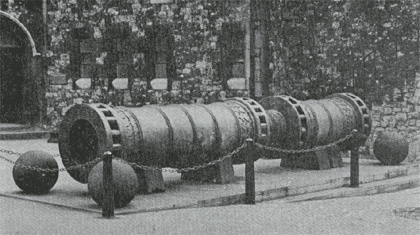

When Constantinople finally buckled and fell in the spring of 1453, it was before the awesome power of the Ottoman siege cannons. A Venetian surgeon, Nicolo Barbaro described the barrage during the desperate final days,

When it fired the explosion made all the walls of the city shake, and all the ground inside, and even the ships in the harbor felt the vibrations of it…No greater cannon than this one was ever seen in the whole pagan world, and it was this that broke down such a great deal of the city walls.

The siege cannons were created by a Hungarian engineer named Orban. He first offered his services to Constantine XI, but the nearly insolvent Emperor couldn’t afford his retainer. He subsequently sought out the young Sultan Mehmet II who immediately understood their potential use in his planned attack on the seat of the dying Byzantine Empire.

The fall of Constantinople was the dramatic final chapter of the Middle Ages. Powerful cannons radically changed the value of walled cities, and thus the nature of international security. The value of walls continued to decline over subsequent centuries as increasingly potent weapons and transportation technologies made walls almost militarily irrelevant. By the late-20th century, a network of fixed fortifications such as the Maginot Line was considered a strategic punch line.

Why Walls Are Back

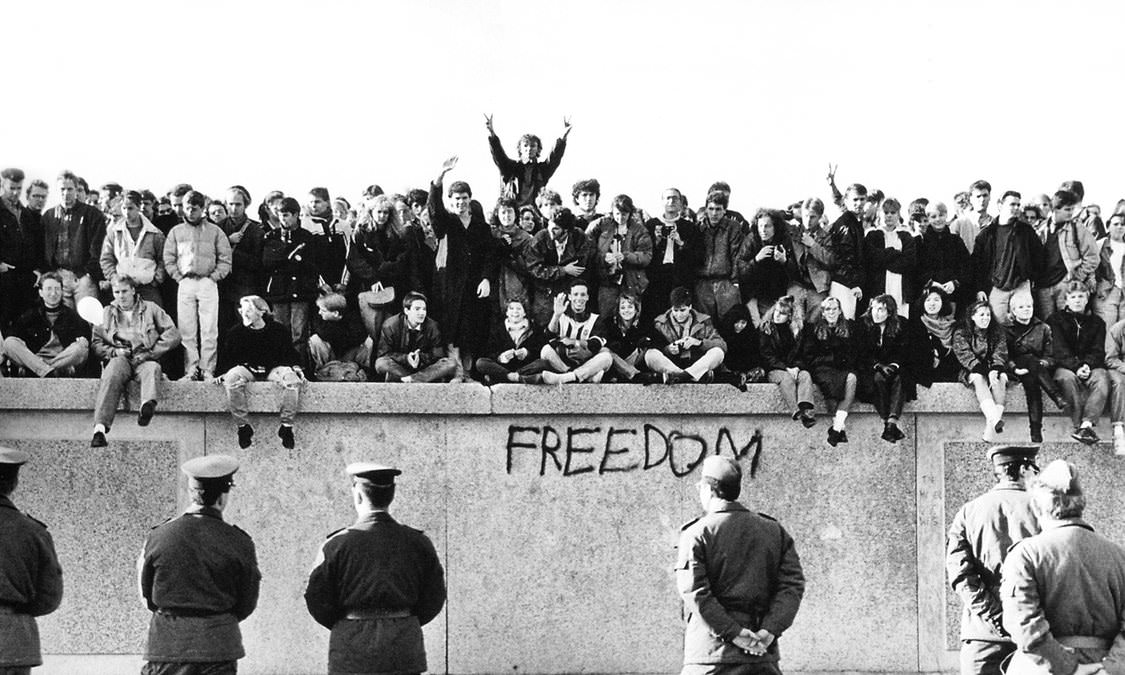

However, after a half-millennia of increasing obsolescence, it seems that walls have staged a comeback. The U.S. government is shuttered today due to a dispute over a southern border barrier. Walls are once again major public policy issues not because of the military threat from a rising China or a revivified Russia, but due to the tsunami of migration flowing from the poorly governed, demographically ballooning areas of Latin America, the Middle East, and Africa. 21st-century walls are not designed to defeat the strong but resist the weak.

Walls are potent political issues today because citizens of afflicted nations are suffering real costs from illegal mass migration. These range from the concrete pains of increased crime and terrorism, to abstract matters like diminished social trust. Though citizens protest, illegal migration continues because a triad of Machiavellian politicians, profit-maximizing corporations, and remittance-receiving states benefit immensely from the current situation. To these actors the system isn’t broken, it has never been better.

Legal migration is a productive activity that pairs skills with opportunities and creates real economic and social value. Illegal migration, on the other hand, is simple territorial competition. Human beings are territorial animals, and disputes over who gets to live where have animated our entire history. In centuries past, such competitions, (for example between Turks and Byzantine Greeks in the 15th century), hinged on who was the strongest. Mehmet’s Ottomans had better technology and were more disciplined, numerous, and organized than the Byzantines. Thus, they conquered and lived in the territory of Anatolia. In the 1450s might didn’t make right, it just made.

To some today, the use of might is always wrong. Beyond those who benefit commercially and politically from illegal migration, there is a set of more pernicious actors: the revanchists of post-modernism. They subscribe to a school of thought that holds that territorial competitions should be arbitrated in favor of whoever is weakest and most aggrieved. For example, in the current territorial competition of Pakistanis trying to illegally move into Germany, the Germans are the “structurally privileged” party and so must now submit.

The practitioners of this ideology are victim supremacists. They hold that the weak of today are that way because of the past actions of the strong, specifically due to actions committed during the historical period of European intercontinental colonialism. By this line of reasoning, modern Germans must make territorial concessions inside their own countries due to the weakness past British inflicted upon past Pakistanis.

This ideology is deeply incorrect both logically and morally.

How can a woman who was born in 1985 in Cologne be considered morally responsible for the actions of an Englishman in 1915 Lahore? If she can be held to account, it begs the question how far historical complicity should reach? Fifty years? Five hundred? Five thousand? Human history is a tale of unceasing cruelty and massacre, and every group in existence today has at some point committed wicked acts of chauvinistic violence.

Is a Zulu South African morally responsible for the displacement and marginalization of the Bushmen that accompanied the Bantu Expansion? Is a Chicano-American living in Los Angeles morally responsible for the cruelties of the Aztec Empire? How should a modern Chinese repent for the Tang Dynasty’s slaughter of 1/6th of humanity during the An Lushan Rebellion?

It is this type of soft-headed, historically ignorant thinking that has precipitated the current crisis, and brought about this new debate over walls, nations, and territory.

Why Walls Work

The plain truth is that walls are effective. They must, of course, be paired with interior enforcement, labor verification, and law enforcement strategies. But the current drive for walls pivots upon the fact that once erected they are the one migration measure that is relatively immune to political oscillations. If a limited-migration administration begins a program of rigorous border enforcement, a subsequent open-borders administration can simply halt it through executive direction. Walls, however, once in place generally stand, and have proved remarkably effective in the 21st century.

In Hungary, the Fidesz government erected hundreds of miles of fencing in the summer of 2015 and watched illegal crossings plummet. The government announced an expansion to this wall last spring, and through physical barriers, the Hungarians seem to have solved their illegal migration problem. Israel has perhaps the most effective border security program in the world. A network of fences and sensors along their southern border is so effective that last year they reported zero illegal crossings. Those who argue that border walls are not effective are either ignorant of these facts or dishonest. In the 21st century, walls are an instrumental component of a sane, humane, legal migration program.

Why Migration Limitations Are Prudent

The velocity and scale of modern migration patterns are truly staggering. And allowing it to take place lawlessly is a geo-strategic blunder. The U.N. estimates that there are 258 million migrants in the world today. Last year one-third of the births in England were to foreign-born mothers. A poll by Gallup revealed that nearly 700 million people globally have a desire to migrate permanently. The pace of migration has increased so sharply because technology has drastically changed the ease of travel.

In the 1830’s migrating from Dublin to Philadelphia entailed a month-long journey on a disease-ridden vessel. 19th-century death rates on trans-oceanic journeys ranged as high as 30%. Today that same journey is a $500, 8-hour flight.

Assimilation is also significantly more difficult today. Upon arriving in 1830s Philadelphia a past migrant’s only ties to their former homelands were unreliable mail and courier networks. Past migrants had little choice but get to know their new neighbors and as Emerson said, “construct a new race, a new religion, a new literature”. Today, WhatsApp, FaceTime, and regular low-cost flights to the old-country make this much less likely. Add on top of these technologies a “salad-bowl” public ethos of ethnic separation and you drastically increase the probability of factionalism and violence.

In the 1450s a perceptive Hungarian named Orban foresaw that cannons would forever change the nature of walls, war, and politics. In a historical dal segno, today it is the Hungarian leader Victor Orban who understands perhaps better than any other Western leader the relationship between walls, war, and politics. He recently remarked that “A mass migration is never peaceful. When large masses of people set out in search of a new home, conflicts inevitably ensue, because others have already settled the place they want to settle. And the earlier settlers will want to defend their home, their culture, and their way of life.” As fierce populist reactions cascade across the Western world, we would be well served to consider this warning.