Art and Culture

Racism, Anti-Racism, and Orientalism at LitHub

Suffice it to say that he hardly comes off as a right-wing cultural warrior seeking to embed himself among the enemy.

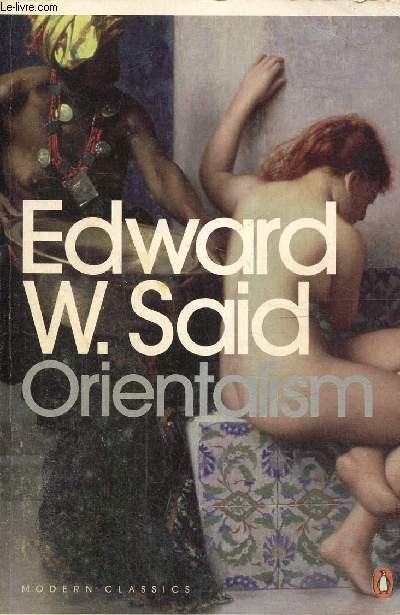

This year marks the 40th anniversary of Edward Said’s Orientalism, one of the most influential works of our time, and one of the most ubiquitous: scan the bookshelves of any liberal-arts major, and you likely will find the 1978 book with pride of place alongside such contemporaneous post-colonial classics as Paulo Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed and Frantz Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth.

Even those who’ve never opened Orientalism will be familiar with some of its broad themes, especially the idea that Western scholars have systematically denigrated the cultures of Asia, the Middle East, and North Africa with insulting stereotypes, depicting the Orient as an exotic “Other” full of backwards, mystical man-children. One sometimes even hears the word used as a verb or gerund — “othering” — as a means to attack arguments perceived to be Eurocentric.

The idea of the Other has become a laugh line among conservatives over time. (“Stop Othering me!”) But even right-wing critics should acknowledge that Said’s book offered genuinely valid critiques of the condescending way in which Western writers often depicted non-Western civilizations. These critiques took on a new urgency after 9/11, when it became common for Western pundits (some of whom had never set foot in an Islamic country) to casually write off the entirety of Muslim civilization as a misogynistic death cult that remains mired in the seventh century.