Alt-Right

The Failed Hero’s Journey

A failed hero is a young person who finds that chaos insurmountable, and is swallowed by its overwhelming force.

There is no more quintessential a model of the failed hero than Elliot Rodger. Rodger, a young man who was promised the world, turned against it when it failed to provide him with eros, love, and romance. His open hand reaching for the future became a fist clenched in opposition, an inversion of the successful hero story. Consumed with jealousy, resentment, and a rejection of the very notion of a healthy human being, Rodger indiscriminately murdered three men in his apartment, and three women at a sorority house. At twenty-two years old, he had chosen to end his life in bitter disappointment, choosing malevolent violence and suicide over the hope of continual and incremental improvement.

Carl Jung understood that those who ultimately reject life itself have failed to experience the archetypal ‘hero’s journey’. To Jung, every single young person who leaves their parents’ home and forages into the world has taken the path of the hero, whether they know it or not. A hero’s journey is simply the departure from comfort, warring against the chaos of the outside world, and the return home with superior wisdom. A failed hero is a young person who finds that chaos insurmountable, and is swallowed by its overwhelming force.

A hero’s journey is simply the departure from comfort, and the return home with superior wisdom.

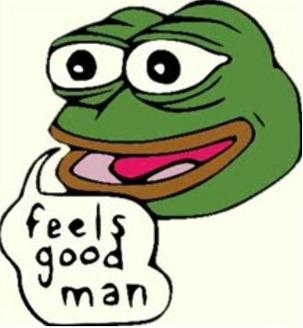

It is then perhaps no coincidence that Pepe the frog is the universal online symbol of young men who find themselves unable to transform order out of chaos. Professor Jordan Peterson describes Pepe the frog as an “emissary of chaos.” Pepe embodies the pain of a generation of young men who believe, to the core of their being, that they have no future. They see the path of the hero, the path of their fathers, of their ancestors who made a life for themselves and earned wealth and had families, as a foregone impossibility. This generation of lost young men, who have invented the term ‘incel’ (involuntary celibate) and NEET (Not in Employment, Education or Training) form the core pessimism of the alt-right, traditionalist and white nationalist sectors of young men who bear the banner of the frog on Twitter and in the forums of 4chan.

Pepe the frog is an online meme/symbol that has become widely popular among disillusioned young men.

The experience of the pessimistic modern young man is evoked brilliantly by a Twitter user named Faceberg, who writes of the promise of employment in STEM fields: “You will never discover anything. You will never invent anything. You will never produce anything of value. Science is so compartmentalized nowadays that you have no idea what you’re working on. A part of a part of a part of some larger part. You’re given a set of instructions to follow and repeat until you find a different lab. There is no room for creativity or innovation.”

This is a bleak portrait of a dead-end world, one where the hopes of prospective heroes are dashed before their journeys even begin. The ascendency of the chaotic frog, and its politicized correlate, President Donald Trump, are only possible in a world that has failed the aspiring hero. After all, it would be cruel and disingenuous to pretend that Faceberg’s pessimism has no rational foundation. Wages have stagnated in the United States. Many new jobs are temporary, without promise of a career or even tolerable pay. Finding a romantic partner has become seemingly impossible for a generation that has sex less often than their parents did, will be too poor to purchase a home, especially not in a major city, and are crippled by student debt. The heroic model of graduating college, finding a job, and building a family has faded in the slow hollowing out of America’s ladder of upward financial mobility. In the chaotic hell of a young man suffering chronic loneliness, a dead-end job, and no prospective future, the devious frog seems to be the most accurate symbol to describe reality.

So where does the promise of a successful hero’s journey come from at all? Carl Jung described the model life of the hero as the “countless experiences of our ancestors…the psychic residue of numberless experiences of the same type.” The accumulated patterns of the past that led to the survival of the human species are the record of the hero’s journey. If the world ceases to produce heroes, then the patterns of human survival come to an end, and so does the future of the human species. A crisis of young men who have lost faith in the world is a crisis of being itself.

The foundational myths of the West, located primarily in The Bible, are filled with the stories of failed heroes, men who were unable to find ultimate faith in the world and took that pain out on others. Myths show us the precedents of our own species, the foundations of ourselves in narrative form. Perhaps there is no deeper precedent to the failed hero than the myth of Cain.

Jordan Peterson, a modern Jungian, describes Cain as the fuming, furious embodiment of one’s resentment at their lack of Earthly success. Anxious, paranoid, jealous and scheming, Cain’s works have been rejected by the world, and so his only response is to attempt to destroy the world.

In killing his brother, Abel, Cain enacts the ultimate tragedy – the murdering of the successful hero. To Eliot Rodger, and to Cain, successful people are the worst of them all. They show that the hero’s journey is still alive, but that they alone are failing to achieve it. But the underlying problem is obvious: if for every ten Abels, married and wealthy, a hundred Cains, single and poor, are produced, then society will become subsumed by Cains, many of whom have a right to be angry. The Trump voters who elected a fool had a right to be angry. Their grievances and fears were real.

To understand those who sympathize more with Cain than Abel in contemporary society, one must sympathize with the downtrodden and hopeless. Young men with no future are perhaps the most dangerous force in all of human history, and ignoring their grievances will not make them go away. It will only make them ferment and grow worse in their stewing, their ruminating, their million arguments against the state of the world.

But there is another side to the downtrodden than that of rebellious Cain. There is another mythical character who has suffered and failed, who chose not to abandon all faith in the world – it is Job. In the Biblical stories, the parallels between Job and Cain are uncanny. Both have lost whatever claim they had to a successful hero’s story, both are chewed and spat up by the random chance and fury of God (or the world, which for our understanding, God and the world are functionally identical). But Job did not turn against the world. No matter how dire his situation became, and how badly God punished him, Job still prostrated himself, apologized, and declared: “I abhor myself/and repent in dust and ashes.”

Carl Jung’s ‘Answer to Job’

In his Answer to Job, Carl Jung argued that Job, in taking God’s abuse and still behaving morally and obediently, had risen above God as a moral being of sophisticated self-understanding. Yahweh’s cruelty was beneath Job. Even though Yahweh had the upper hand in every possible way – he was beneath Job as a conscious moral actor. In exalting a human man above God, the myth of Job showed that the world’s ethics could be overcome by a superior hero.

Radically, Jung wrote that God “is not human, but in certain respects, less than human.” God was “unconscious”, a tyrannical force much like the Leviathan, as “unconsciousness has an animal nature.” If God’s world is unconscious and cruel, but Job is moral and good, then the entire trajectory of human life is to redeem the incomplete world created by an incomplete God. Jung wrote: “The real reason for God’s becoming man is sought in his encounter with Job.”

Instead of cursing God and rebelling against existence, Job acted morally in an immoral world – and because of it, the purpose of man became higher than the purpose of God. The creator of the universe, in the book of Job, was an unconscious monster, and his own creation was a faithful moral hero. The creation surpassed the creator on the moral plane. It is perhaps one of the most staggering stories ever told.

The entire hero’s journey is defined by the distance between Job and Cain. One has a future – one does not. Both are dealt an unjust hand, but the responsibility of the individual is to act as a moral exemplar despite the immoral world. Handed injustice, one can become greater than the world or far lesser. And it is all in the hands of the individual. If there is any message more Christian, traditional and powerful than that, I do not know it.

Alexander Blum is a writer with a focus on politics, fiction and mysticism. Follow him on Twitter@AlexanderBlum0