liberalism

Why Liberals Are Turning Against the Internet

The bonds of nationalism, ethnicity, and religion would either wither away or perhaps allow numerous tribes to co-exist in and open and tolerant multicultural setting.

Following the news of late might lead one to conclude that Mark Zuckerberg is America’s Public Enemy Number One, and that the World Wide Web is destroying the foundations of the country’s democratic system.

“Silicon Valley Is Not Your Friend,” cried a recent headline in The New York Times. Perhaps surprisingly, the long article below called for federal regulation of the destructive and arrogant information high-tech companies now being blamed for the election of President Donald Trump and much else besides. Having spent years telling its readership that Zuckerberg was a revolutionary innovator and boy genius, The New York Times has had second thoughts. If you believe that the most pressing danger facing the American Republic is sitting in the White House, the author explained, then think again. Apparently, it’s hidden in Silicon Valley.

So, let us go back to the early days of the 21st century, when celebrating the promise of the Internet was just another way of asserting your commitment to liberal principles, democratic ideals, human rights, and political and cultural freedom. Innumerable opinion pieces were penned, studies conducted, and speeches delivered explaining that this new technology would empower the powerless, allowing them finally to influence the public debate and the policy process, and thereby confront the mighty.

“Connecting” the people to the Internet, supplying personal computers to each and every American, and ensuring that every community had access to Wi-Fi, would accelerate political change. It would encourage more Americans to vote and create the foundations of a participatory electronic democracy energized by social media sites like Facebook and Twitter. The political, social, and economic implications of the Internet Revolution also promised success for the post-Cold War drive towards global political and economic reform. It would link markets, join societies together and interweave the world’s cultures.

The Internet would challenge the concept of the archaic nation-state and lead to the creation of supra-national institutions and the evolution of a new Global Village. The bonds of nationalism, ethnicity, and religion would either wither away or perhaps allow numerous tribes to co-exist in and open and tolerant multicultural setting. And it would help strengthen the hands of minority groups, feminists, and gay activists here, there, and everywhere – including on social media, of course – allowing them greater freedom to communicate, co-ordinate, and organise.

Not everyone, of course, was carried away by this utopian vision, but the political bottom line was clear: any infringement on Internet freedom amounted to an assault on liberal principles, and constituted an unacceptable obstacle to the March of Progress.

Starting with President Bill Clinton, the titans of Silicon Valley would become natural allies of liberal Democratic politicians who were committed to protecting the interests of the owners of Microsoft and Apple, Facebook and Twitter. The oratory employed by leading Democrats like President Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton, sometimes created the impression that Bill Gates and Steve Jobs, Mark Zuckerberg and Sergey Brin, weren’t just ordinary business entrepreneurs hoping to make a lot of money. They were the prophets of a new Enlightenment, and only culturally backward types repulsed by pornography, or authoritarian personalities citing national security concerns, would attempt to stand on the way of these agents of global change.

It is the Clinton Administration and its Telecommunications Act of 1996 that should be credited (or blamed, depending on your point of view) for deciding not to treat the Internet as a public utility requiring regulation. This decision allowed free market forces and technological innovation to shape the so-called “information superhighway” with minimal government intervention. And so, a political alliance between the liberal elites in Washington and the tech billionaires in Silicon Valley and Seattle was forged.

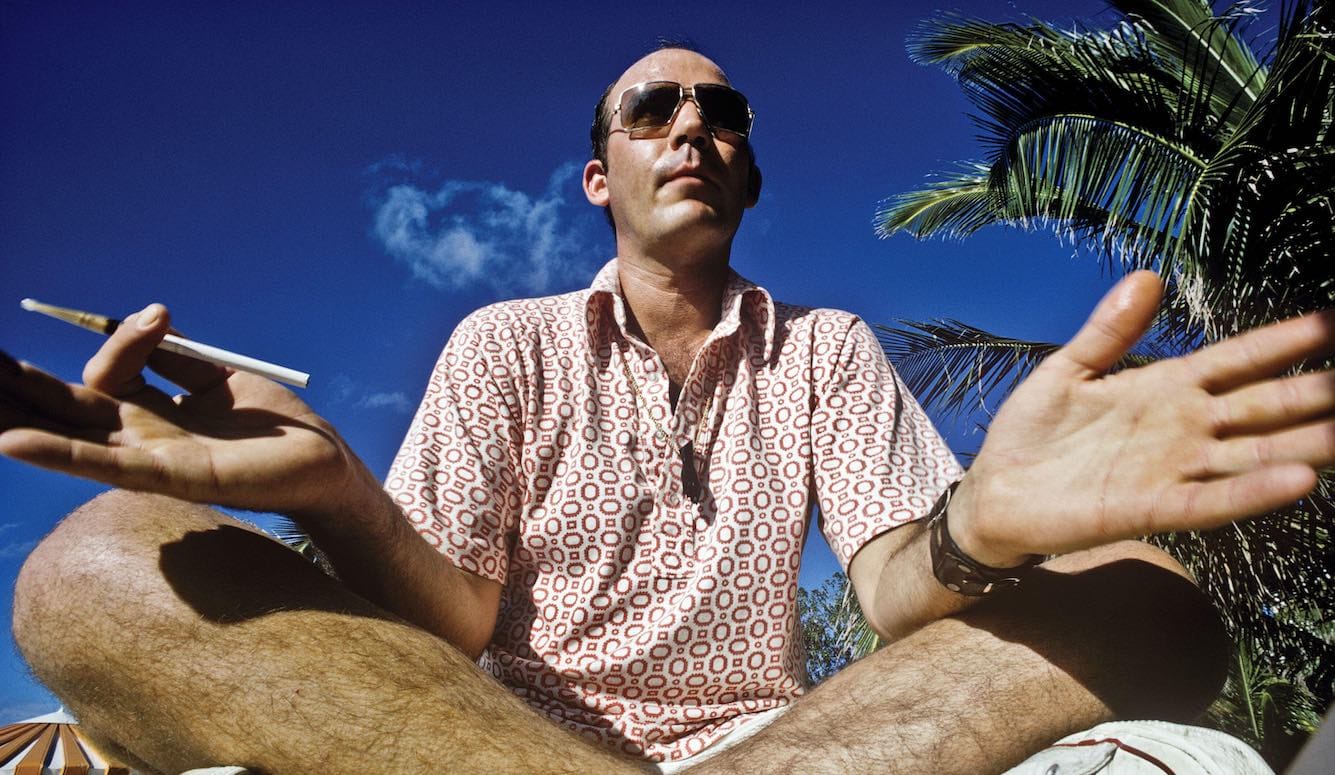

As it happens, seventeen years ago, it was also President Clinton who suggested that attempting to control the internet in China would be like trying to “nail Jell-O to the wall.” Echoing the views of political and economic liberals, Clinton asserted that, by opening up the world to its users in China and in other closed societies, the Internet would weaken the power of authoritarian regimes everywhere. In concert with the liberalizing influence of globalization, and led by the rising educated and professional middle classes in China, Russia, and Iran, citizens would be newly empowered to demand political change. The revolution would be tweeted not televised. Or as John Perry Barlow enunciated in his 1996 “Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace,” no government would be able to crush the Internet’s libertarian spirit.

It wasn’t surprising, therefore, that Democratic administrations placed the concerns of Microsoft, Apple, Facebook, and Google at the top of their agenda when they negotiated trade deals with China and other authoritarian regimes. Their opposition to government restrictions on these companies wasn’t framed as a part of a campaign to promote the business interests of Gates and Zuckerberg, but as way of advancing freedom of information in China and elsewhere. It all sounded so intellectually neat, especially if you were philosophically inclined to embrace the idealists’ mantra. The shadows in Plato’s cave were not those of greedy corporations, but the forms of the inheritors of the political legacy of the 1960s.

Unfortunately, things have not gone according to plan. To trace the beginning of the end of the love affair between liberalism and the Internet, recall that these utopian expectations were, as The Economist’s Gadi Epstein observed, confounded in China:

Not only has Chinese authoritarian rule survived the Internet, but the state has shown great skill in bending the technology to its own purposes, enabling it to exercise better control of its own society and setting an example for other repressive regimes. China’s party-state has deployed an army of cyber-police, hardware engineers, software developers, web monitors and paid online propagandists to watch, filter, censor and guide Chinese internet users.

“The internet,” Epstein concluded, “was expected to help democratize China. Instead, it has enabled the authoritarian state to get a firmer grip.”

The love affair between Washington, DC and Washington State lasted as long as it did because many liberals embraced a technological deterministic approach, which postulated that the inherent nature of media technology would drive political change. Marshall McLuhan’s meaningless slogan, “The Medium is the Massage” [sic] was transformed into a grand political theory. Which was odd, since the Canadian publicity seeker was a literary and cultural critic, not a social scientist. The Internet, contended the neo-McLuhanists, would provide citizens with increased access to information and facilitate easy communication with others at home and abroad who shared their views. That, in turn, would erode the power of governments while strengthening the hands of those confronting them.

In The Net Delusion, Belarus-born American scholar Evgeny Morozov challenged this received wisdom and, in particular, the notion that social media companies such as Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube were becoming agents of political change capable of toppling authoritarian regimes in countries like Egypt. Not so, argued Morozov. He was skeptical that cyberspace is conducive to democracy and liberty, and he strongly criticized the belief that free access to information, combined with new tools of mobilization afforded by blogs and social networks, would lead to the opening of authoritarian societies and their eventual democratization. For that matter, he disputed that it would serve as much of a progressive force in the liberal-democratic societies of the West.

But the McLuhan narrative was the narrative The New York Times and other media outlets embraced when they covered the 2011 demonstrations in Tahrir Square in Cairo and the ensuing resignation of the country’s president, Hosni Mubarak. They created the impression that a bunch of young, hip, Internet-savvy Egyptians had succeeded in using social media to mobilize hundreds of thousands of their countrymen. They had protested against Mubarak by blogging, tweeting, Facebooking, You Tubing, and Googling their way to Cairo’s Tahrir Square, and from there they would go on to win liberty and democracy.

But, as in China, these dreams were illusory. The political upheaval unleashed by the demonstrations allowed two anti-democratic forces to come to power: first, the powerful Islamist movement the Muslim Brotherhood, and then a military clique which, like the Communist regime in China, is now using the Internet to track down dissidents and to dispense propaganda. In short, the Egyptian regime is using the Internet to strengthen its hold on power. The medium was not the massage and the revolution was not tweeted, after all.

Each new information technology, from papyrus through the printing press to the telegraph and, yes, the Internet, provides new tools for empowering political actors, including revolutionary movements and other opponents of the status quo. But each new technology can play a role only in the context of wider political, economic, and cultural development. Technology by itself cannot transform the existing balance of power. It can only assist those players who are already confronting the status quo or those attempting to preserve the old order. The people, not the media, design and demand political change or try to contain it.

Materialists and those with a conservative view of history questioned the idealists’ optimistic faith in the power of inexorable progress – whether embodied by new information technologies or international institutions and legal mechanisms – to remake our political and economic realities. As Morozov crisply put it, “Technology changes all the time; human nature hardly ever.”

There is really nothing either “good” or “bad” about any media technology. The printing press published both Adolph Hitler’s Mein Kampf, the American Declaration of Independence, and a lot of silly romance novels. The radio was employed by both Hitler and Franklin D. Roosevelt to advance their very different political agendas. Television beams performances at the New York Met straight into our living rooms as well as mind-numbing soap operas and reality shows, while movie theatres introduced us to Citizen Kane as well as to Deep Throat (and who is to say which of the two films had the greater impact on our culture?).

The problem, in case you haven’t noticed, is that political players tend to blame the media for their losses. After the loss of an election, or any other political battle, the tendency is to blame someone or something else for the defeat: negative press coverage or lousy television commercials or poor media advisors or what-have-you. After all, why else would a great candidate with a noble message be rejected by the electorate? At the same time, when analyzing politics and political campaigns, journalists and pundits are more inclined to focus on the micro (including media stories) at the expense of the macro (like economic and social changes) in an attempt to explain political events.

To put it in more concrete terms: why blame former Democratic presidential candidate Hillary Clinton’s election loss on her failure to reach out to white blue collar voters in Pennsylvania and Ohio when you can blame Facebook and Google for disseminating Russian propaganda and fake news? Google and Facebook once enjoyed the ear of Barack Obama and the close attention of Hillary Clinton, and served as a revolving door for Democratic White House and Congressional staff. All concerned pledged to advance their mutual interests and embrace shared values of openness and freedom. But now both companies are playing the role of the villains in a liberal narrative that seeks to evade liberal responsibility for Clinton’s electoral defeat.

Of course, a totally different Democratic and liberal narrative held sway when Obama’s presidential campaigns employed the tools of the Internet, including social media, to help get him elected twice. Back then, Facebook, Google, Twitter, and YouTube, like the Obama Administration, still represented progress and the spirit of the youth; the urban and cosmopolitan centers of the country; the future. But now that the Democratic candidate had lost the presidential race, Zuckerberg and the other chiefs of social media are held responsible for empowering racists, homophobes, and misogynists, and for allowing the leader of Reactionary International, Russian President Vladimir Putin, to “interfere” in the presidential campaign and get his preferred choice, Donald Trump, elected.

Never mind that the loser in the 2016 presidential race and her allies spent about $1.4 billion on her campaign, including ads, compared with the roughly $1 billion spent by the winner. Or that some of the best media strategists on the planet were working on Clinton’s campaign. Or that the entire elite media concluded that Hillary had “won” all the presidential debates. Or that every fresh news cycle seemed to bring a new New York Times or Washington Post exposé expected to destroy Trump and his campaign. According to the new narrative, the election was won by accounts associated with Russia placing $100,000 of ads on Facebook and trolls posting disinformation and fake news online.

These inept and amateurish propaganda efforts may sound ominous. But as Democratic campaign consultant Mark Penn explained in The Wall Street Journal, there is no evidence that these Facebook ads and fake news had any effect on the election outcome. Penn calculated that only half of the allegedly Russian ads went to swing states, and further noted that, in the last week of the campaign alone, Clinton’s Super PAC dumped $6 million on ads into Florida, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin. “Even a full US$100,000 of Russian ads,” he wrote, “would have erased just 0.025 percent of Hillary financial advantage in the campaign.”

Nevertheless, Democratic lawmakers, who until recently fawned over Zuckerberg and other captains of the information high-tech industry, are suddenly discovering that Facebook and Google are “too big”; that they exert too much political and economic power; that they may not have the interests of the American public at the top of their agenda; and that the government has to get in and regulate the Internet, even if that means curtailing some of the freedoms liberals like to celebrate. Democrats and liberals are shocked to discover that Facebook and other Internet companies are not forces advancing political progress, but businesses seeking to make a buck, including selling ads to Russian customers.

Sensibly, a decision about whether and how to regulate these companies should be based first and foremost on weighing the need to allow the market to operate freely, on the one hand, against the interests of the public on the other. Unfortunately, the political backlash against the Internet from the Democrats is occurring at a time when some conservative Republicans are also arguing that the information high-tech industry is getting too powerful and should be regulated like a public utility. The irony is that these traditionally pro-free market conservatives are turning against Facebook and Google because they regard them as political allies of the Democrats and as promoters of liberal social policies on immigration, transgender rights, and so on.

After Google dismissed James Damore, an engineer who wrote about gender differences and said the company had a “left bias,” Republican Representative Dana Rohrabacher, tweeted that:

Fox News television host, Tucker Carlson, has argued Damore’s dismissal showed that Google can’t be trusted to design algorithms determining where to rank fake news when returning search results. “Google should be regulated like the public utility it is,” he said, “to make sure it doesn’t further distort the free flow of information to the rest of us.” Meanwhile, Representative Marsha Blackburn, the Tennessee Republican who leads the House communications subcommittee, has recently introduced a bill to bring web companies and broadband providers alike under one privacy regulator.

So after years of championing an open and free World Wide Web in the public interest, it seems that Democrats may now be joining forces with Republicans to argue that the information highway operates against the public interest and therefore requires government regulation. This is a depressing political reality for those of us who have never considered the Internet a revolutionary or utopian force, but who hoped that under the right political and economic conditions, it could help fortify liberal principles in a free and open society.