Free Speech

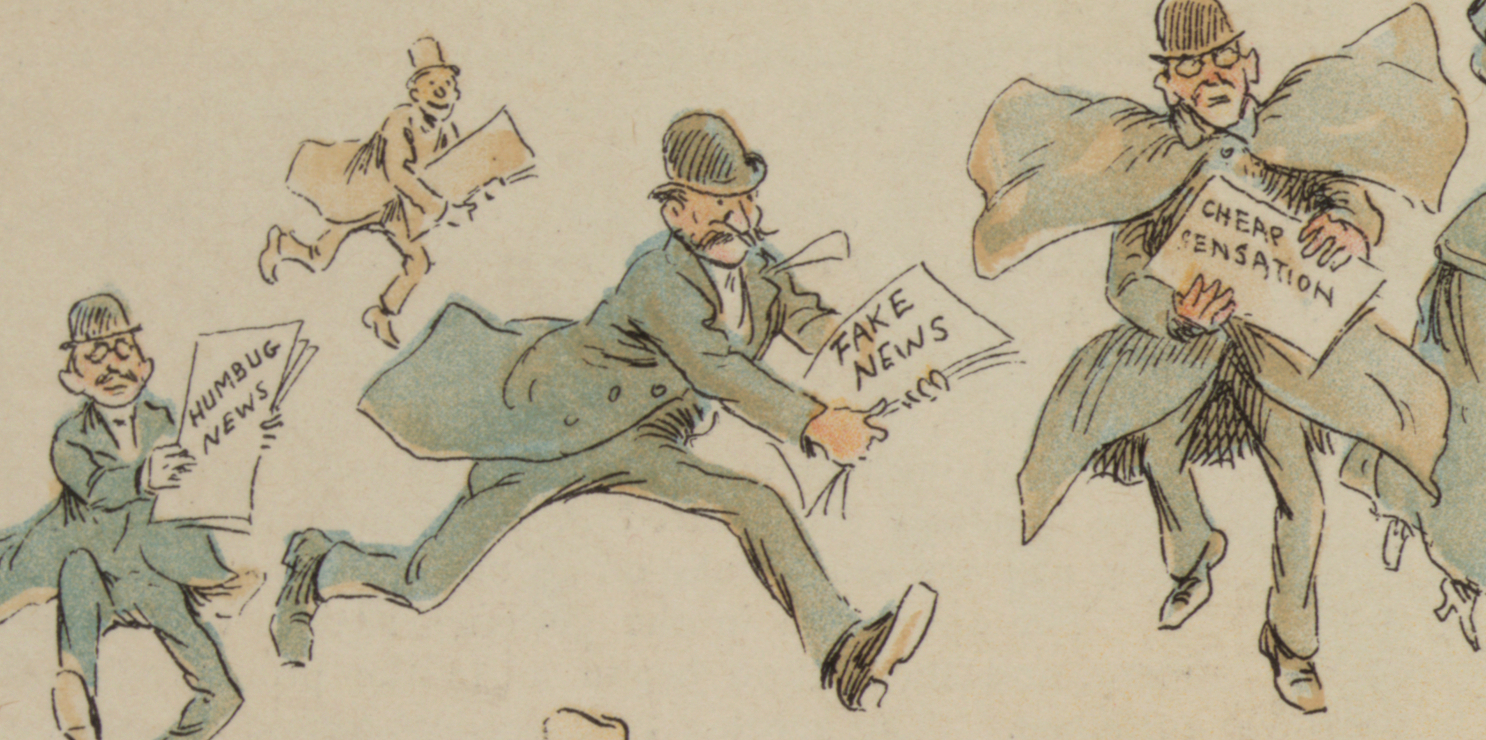

Fake News is Old News

News and information thus become weaponized and aimed against the very institutions and values that free speech was supposed to protect.

“Fake news,” disinformation, and propaganda is saturating social media and driving the content of important political conversations among citizens in otherwise enlightened democracies. News and information thus become weaponized and aimed against the very institutions and values that free speech was supposed to protect. That, at least, is the fear among many politicians and pundits. These fears have been given impetus by the role of alternative and social media in the 2016 American Presidential election and by a number of studies exploring the “eco-system” of alternative media and the misinformation sown, grown, and distributed by such outlets.

This scenario has precipitated a collapse of public trust in democratic institutions, and governments fearful of populist nationalism have scrambled to find policies aimed at combatting fake news. Germany recently adopted legislation obliging social media companies to pay fines up to EUR 50 million if they fail to delete illegal content within 24 hours. While ostensibly aimed at hate speech and defamatory slander, German minister of Justice Heiko Maas has blurred the lines between these categories and the ill-defined concept of “fake news.”

Italy introduced a bill aimed at “preventing the manipulation of online information” with fines of up to EUR 5,000 for “non-journalistic” websites, social media etc. that publish or disseminate “fake, exaggerated or tendentious news regarding data or facts that are manifestly false or unproven.” Creating or disseminating “rumours or fake, exaggerated or tendentious news that may provoke public alarm or acts in a such a way as to damage public interests or mislead the public opinion” is punishable with up to 1 year in prison.

In December 2016, EU Commissioner for Justice Vera Jourova stated that “social media companies need to live up to their important role and take up their share of responsibility when it comes to phenomena like online radicalisation, illegal hate speech or fake news.” In the European Parliament MEPs seem split between those advocating European-wide legal measures aimed at combating fake news and those worrying that such a move would entail an unacceptable level of censorship. As German EPP member Monika Hohlmeier argued, “We do have freedom of opinion, but you don’t have alternative facts, you just have facts. It’s essential that we take legal measures at the EU level so that we can react effectively.”

In the US, the First Amendment would bar Congress from adopting similar laws, yet President Trump has repeatedly railed against “fake news.” On 30th March 2017, he tweeted:

The failing @nytimes has disgraced the media world. Gotten me wrong for two solid years. Change libel laws? https://t.co/QIqLgvYLLi

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) March 30, 2017

This was a softer reiteration of a campaign pledge to “open up our libel laws so when they write purposely negative and horrible and false articles, we can sue them and win lots of money.” Apparently, this message resonates with a substantial part of the American population. Asked in an Economist/YouGov poll whether courts should be able to “shut down” media outlets for “publishing or broadcasting stories that are biased or inaccurate,” 28 percent were in favour, 29 percent were opposed, whereas 43 percent were undecided. However, a plurality of 45 percent of Republicans were in favour of this draconian move. And a full 55 percent of Republicans favoured fining such “biased or inaccurate” media outlets, compared to 34 percent approval overall, with only 20 percent opposed.

It is, however, important for politicians and citizens to keep in mind that the discussion over what we today label “fake news” is not a new phenomenon born in the digital age with the advance of social media. Information has always been contested. Especially at times of great political and social upheaval and the emergence of new information technologies. In fact, we find a famous incident in antiquity. The Greek writer and historian Plutarch was extremely critical of the influential Greek historian Herodotus – ”the father of history” – whose Histories details, among other things, the Greco-Persian Wars in Fifth Century BCE “I think myself obliged to defend our ancestors and the truth against this part of his writings, since those who would detect all his other lies and fictions would have need of many books,” wrote Plutarch some 500 years after Herodotus.

When Christianity became the state religion of the Roman Empire in 380 CE, ensuring orthodoxy in belief became a focal point for successive emperors. Christianity was not only wound up with the legitimacy of the emperor, whose power derived directly from God, but also with the safety, happiness, and success of the empire, which God would punish if its rulers and citizens strayed from the truth. Orthodoxy was therefore not just a matter of belief, but one of national security. Heretics were not just doomed to miss out on salvation, but actively endangered the lives of their orthodox co-citizens. Emperor Justinian’s celebrated and deeply influential Code of Roman laws is filled with imperial decrees aimed at heretics and pagans: “Let all heresies forbidden by Divine Law and the Imperial Constitutions be forever suppressed….Let no place be afforded to heretics for the conduct of their ceremonies, and let no occasion be offered for them to display the insanity of their obstinate minds.” Book burnings, banishment, and in some cases death, were some of the measures employed to ensure that the truth would prevail.

Kings were also concerned about ideas challenging their legitimacy. As early as 1275, Edward I enacted England’s first seditious speech act prohibiting anyone from “cit[ing] or publish[ing] any false news or tales whereby discord or occasion of discord or slander may grow between the king and his people or the great men of the realm.”

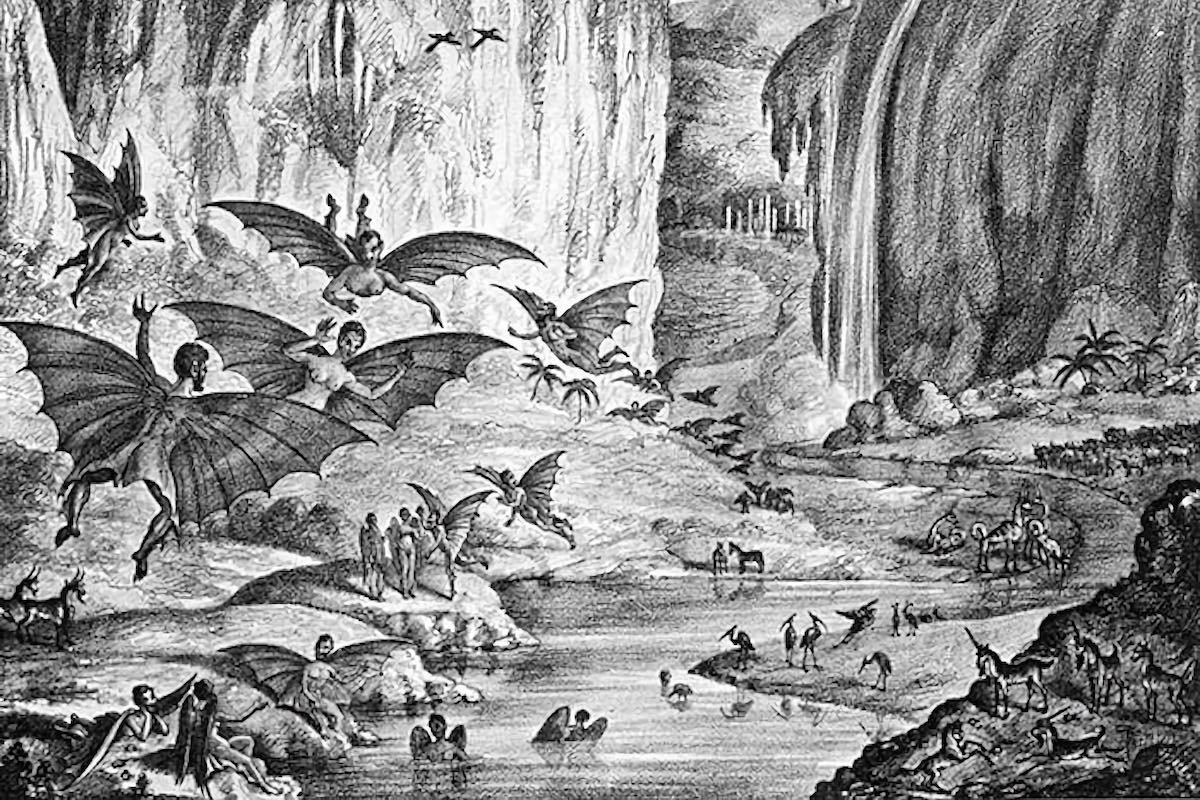

The combination of the printing press and the soon-to-follow Protestant Reformation saw the institutionalization of censorship across Europe. Rulers, priests, and popes were panicked about ideas and doctrines that threatened the status quo and were spreading with unprecedented rapidity and reach. The most famous example is the Catholic Church’s Index of Censorship, whose persecution of “error” was defended on the premise that “Freedom of belief is pernicious, It is nothing but the freedom to be wrong.” But Protestant states would also guard their official and monopolized versions of the “Truth” against competing sects. In England, the number of permissible printing presses was tightly regulated and books were licensed.

The effects of the Renaissance and Reformation gradually ensured that religion would no longer be the sole dominating object of public discourse. Free standing discussions of philosophy, science, and politics would emerge, culminating with the Enlightenment. Accordingly, rulers would have to justify their power and legitimacy – and the suppression of perceived threats thereto – on other grounds than strictly religious ones.

In the 17th Century, several American colonies – including Massachusetts, New York, Virginia, South Carolina, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and Maryland – adopted laws aimed at suppressing “false news” thought to endanger the authority of local governments and thus the social peace of which these governments where the guarantor. A New York statute from 1664 (reaffirmed in 1684) punished those “who shall wittingly or willingly forge or divulge false news whereof no certain author,” whereas the Assembly of South Carolina ordered three months’ imprisonment for anyone who “presumed to publish any false news or utter any seditious or scandalous words tending to the disturbance of the peace of this government.”

During the French Revolution, public opinion was violently contested. Several revolutionaries initially celebrated “The free communication of ideas and opinions” enshrined in article 11 of The Declaration of The Rights of Man. But as the Revolution turned to Terror, radicals such as Robespierre chose to emphasize the same article’s warning against “abuses of this freedom.” In 1794, the Committee on Public Safety adopted a law tasking the Revolutionary Tribunal with “punishing enemies of the people” which included “Those who have disseminated false news in order to divide or disturb the people” and “Those who have sought to mislead opinion and to prevent the instruction of the people.” The punishment for such a transgression was death and many were guillotined for the circulation of news and opinion.

American independence and the adoption of the Bill of Rights and its First Amendment strengthened free speech in the United States immensely. But the limits of free speech would soon be contested due to the threat of war with France and the antagonism between Federalists led by president John Adams and his political rivals in the Democratic-Republican Party led by Thomas Jefferson. In 1798, Federalists managed to pass the Alien and Sedition Acts, which included a penalty of up to 2 years imprisonment for publishing “false, scandalous and malicious writings” with bad intent or that defamed the government, Congress, or the president. Jefferson was vehemently – but not publicly – opposed to the Act. As minister to France, he had written to a friend “were it left to me to decide whether we should have a government without newspapers, or newspapers without a government, I should not hesitate a moment to prefer the latter.”

When Jefferson became president, he held an inauguration speech promising Americans the right “to think freely and to speak and write what they think,” and the Act expired. But when in power, Jefferson himself soon became disillusioned with the press. In a letter from 1803 he wrote that Federalist newspapers undermined press freedom “by pushing it’s licentiousness and it’s lying to such a degree of prostitution as to deprive it of all credit….I have therefore long thought that a few prosecutions of the most eminent offenders would have a wholsome effect in restoring the integrity of the presses.” In a letter from 1807, Jefferson gave the following verdict of the American press: “Nothing can now be believed which is seen in a newspaper. Truth itself becomes suspicious by being put into that polluted vehicle”

The 20th Century would see the emergence of totalitarian ideologies, the leaders of which would be scrupulous in using disinformation and propaganda for their own purposes while equally obsessed with denying any public or private space to deviation from the party line, as determined in Berlin or Moscow. As Lenin bluntly put it, “ideas are much more fatal things than guns. Why should any man be allowed to buy a printing press and disseminate pernicious opinions calculated to embarrass the government?”

But it was not only in totalitarian states that misinformation and propaganda thrived in the 20th Century. George Orwell, perhaps the era’s greatest champion of free speech, commiserated on what he saw as an onslaught of lies and propaganda penetrating even democracies such as Britain. In his 1943 essay “Looking Back on the Spanish War” George Orwell lamented that: “I saw newspaper reports which did not bear any relation to the facts, not even the relationship which is implied in an ordinary lie…..; and I saw newspapers in London retailing these lies and eager intellectuals building emotional superstructures over events that had never happened.”

Despite Orwell’s frustration he was nothing if not principled and fought “the widespread tendency to argue that one can only defend democracy by totalitarian methods” and by targeting those who are “spreading mistaken doctrines.” Orwell saw clearly that “if you encourage totalitarian methods, the time may come when they will be used against you instead of for you.” It is this essential insight of Orwell’s that democracies are now tinkering with when taking aim at fake news through legal means.

The fact that the truthfulness of news, reporting and information has always been contested does not necessarily mean that the reaction to current developments in the digital age should be shrugged off as a moral panic without any merit. But it should caution decision makers tempted to adopt draconian measures without fully understanding the likely consequences. The preceding history reveals the dangers of putting governments and institutions in charge of defining truth and error.

No doubt most kings, emperors, and popes were sincere in their belief that their version of orthodoxy was the truth and that deviations therefrom necessitated suppression of dissent, heresy, and apostasy. But liberal democracy’s commitment to individual liberty necessarily entails the right of individuals to reject and (peacefully) oppose the very tenets of the liberal order. In fact, this commitment is built in opposition to the idea of monopolizing truth and on the premise that freedom of thought, expression, and private judgement in matters secular and religious belongs to the individual and not the government, however large its democratic mandate. The progress in science, freedom, culture, and art taken for granted in our age has been constructed piecemeal on the ruins of dogma held as truth by previous ages, but demolished or refurbished by the development and advancement of new ideas, information, and opinion.

A “ministry of truth” will inevitably become the guardian of the status quo, arresting the spread of competing ideas that may demonstrate the lack of merit of ideas we currently hold central, as well as limiting our capacity to fully grasp and defend those of our fundamental ideas that still merit observance.

The Guardian view on censoring the internet: necessary, but not easy | Editorial https://t.co/pX6g40BbUu

— Guardian Law (@GdnLaw) August 21, 2017

There is also an acute danger that laws against fake news will be abused. When does a government’s restriction of “fake news” aimed at safeguarding the institutions of democracy become a useful tool aimed at limiting the spread of information undermining the worldview of the powers that be? Jefferson’s temptation to use law against opinions should tell us that human nature has an inherent tendency to convince itself that positions of power rest on a foundation of unassailable truth and legitimacy.

In Europe, the concern about fake news is aimed at so-called right-wing populists, who are against globalization, immigration, sceptical of the EU, and hostile towards Islam. But an EU-directive against fake news would very likely see populist leaders such as Hungary’s Victor Orban and the current Polish PiS government implement such measures very differently to a German government under Angela Merkel. Should the current US administration somehow find a chink in the armour of the First Amendment, a new Sedition Act against fake news would undoubtedly be aimed at mainstream media outlets such as the New York Times and CNN. And with such a precedent in place a new Democratic administration and Congress would surely be tempted to recalibrate the scope and take aim at hyper-partisan conservative alternative media outlets.

Asked if it would have been preferable to retain the imperial laws against heretics, the Index of Censorship, the limits on permissible printing presses, the death penalty for spreading false news in Revolutionary France, or the Alien and Sedition Acts, most people today would likely answer with an emphatic “No.” That these restrictions of free speech now seem indefensible should serve as a warning against rebooting censorship in the digital age.