History

What to do with Confederate Statues?

Many Russian people lived through the Soviet experience. Not so for the Confederacy.

Could Russia teach us something about how to deal with difficult aspects of our national history?

Many places in the South – from New Orleans to Louisville – are in the process of bringing down statues that glorify the Confederacy. That process raises questions about what to do with these remnants of the past. Do we just toss them into the ash bin of history, purging them as if they never existed?

As a student of southern politics who recently traveled to Moscow, I wondered if we can look to the Russians and how they have treated their Soviet past. The situations are not perfectly analogous. Many Russian people lived through the Soviet experience. Not so for the Confederacy. That said, in both cases, there is the question of whether – and how – to purge the past.

From propaganda to kitsch

In Moscow, and in the former Soviet Union in general, there is Soviet detritus all over the place. Hammers and sickles are chiseled into buildings, bridges and other infrastructure. Sculptures of happy, heroic soldiers, workers and farmers sit on the platforms in the Moscow metro. Seven massive “Stalin buildings” dot the city.

The Russians have done more than just tolerate these leftovers. All the propaganda that the Soviets used to produce and disseminate – and there was a lot of it – is now kitsch. Kiosks sell Soviet T-shirts next to matryoshka dolls and amber jewelry as genuine Russian souvenirs. As one Russian gentleman said to me, “It’s our past and we embrace it. We lived it. We can’t just wish it away.”

It would not be very practical to knock down the buildings Stalin helped to build or hammer out all those hammers and sickles.

Statues, however, have no practical purpose and can be taken care of rather easily. Moscow has removed many of them from public space. It was one of the first impulses the Russian people had after the fall of the Soviet Union.

What is instructive is what the Muscovites have done with their statues, collecting them in a sculpture garden and giving them historical context.

A grove of Lenin statues

The statues and monuments now reside together in a section of MUSEON Arts Park, a lovely green space next to Gorky Park. MUSEON is also known as the Fallen Monument Park, though “felled monuments” would be the more appropriate name. The park contains more than just felled Soviets. There are hundreds of other pieces sprinkled through the park. But walking through the grove of Lenin statues, sitting in the shade of a monumental Soviet coat of arms, or posing next to a large bust of Leonid Brezhnev or Mikhail Kalinin is the thrill for people like me.

Each statue or set of statues is accompanied by a panel that informs the viewer about the work, its composition and the history of its display. Notably, there is little about the leader being portrayed in the text. Each description ends with, “By the decree of the Moscow City Council of People Representatives of Oct. 24, 1991, the monument was dismantled and placed in the MUSEON Arts Park exposition. The work is historically and culturally significant, being the memorial construction of the soviet era, on the themes of politics and ideology.” The point, of course, is that the Moscow city council is careful to state that the display is not intended to glorify the past, but to document it.

What is even more powerful is how the statues are displayed. In some ways, the arrangements are reminiscent of a cemetery. White, granite “tombstones” line a path, an appropriate metaphor for the Soviet regime.

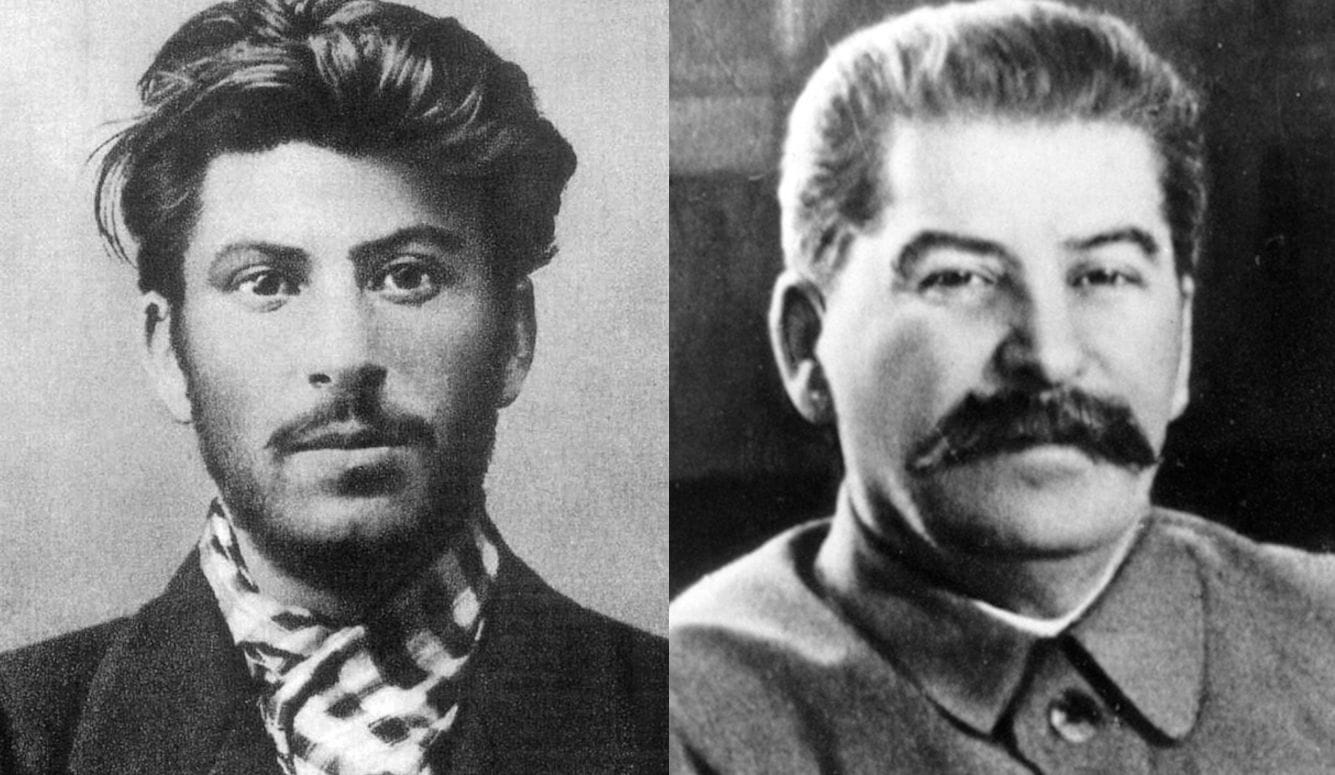

It is the large statue of Josef Stalin, however, that is most striking. Stalin has lost his nose and is in sad shape. Behind him is a monument to the “Victims to the Totalitarian Regime.” The monument is a wall comprising stone heads cocked at different angles. The heads are held in place by a grid of bars and barbed wire that evoke a prison camp. Hundreds of these victims stare at Stalin. Indeed, because of their placement, one cannot look at him without looking at them.

Moreover, in front of Stalin is a contemporary statue of Russian physicist and Nobel Peace Prize winner Andrei Sakharov, one of the most notable dissidents of the Soviet era. The statue of Sakharov is seated, arms behind his back, legs and feet locked together, and head upturned to the sky. Is he staring at the stars, not an unreasonable thing for a scientist or a disarmament activist to do, or can he just not bear to look at Stalin directly in front of him? And what about those arms stretched behind his back, one of them twisted and unnatural, fist in a ball? Is Sakharov being detained, or tortured? That interpretation is suggested by the statue of Felix Dzerzhinsky, the founder of the KGB, who faces Sakharov about 50 yards away. It is quite delicious to see a dog passing by and marking “Iron Felix.” Perhaps Sakharov is just having a good laugh.

Why do these scenes, these dead Soviet statues, work so well? I would assert that by locating them together, they can be put into “historical and cultural” context, as the markers suggest. Moreover, through strategic curation, these statues have been put into dialogue with each other and with the contemporary sculptures around them and been given new meaning. The statues in their old lives were meant to honor and glorify the Soviet leaders and their regime. In their new life, they have been turned into art. As pieces of art, their meaning can be changed or supplemented by how the viewer interprets them.

This suggests there would be real value to bringing felled Confederate statues together in one place. Putting them into historical context, they can give commentary on the Confederacy, the Civil War, slavery, Jim Crow, massive resistance and even present-day politics. And locating these statues with other monuments offers all kinds of opportunity to tell the whole story of the South.

This article was originally published on The Conversation.