Art

Confessions of a Hello Kitty Killer: The Pernicious Effects of Cuteness

Ranked by concentrated cutesiness, the ‘original’ smiley faces that launched a fad and first bothered me as a kid didn’t pack the punch of what they would devolve into.

Call me a sociopath, but I’ve always had a problem with things conspicuously cute. As a child growing up in the sixties and seventies, unlike most of my peers, I couldn’t help but see something creepy, even sinister in those smiley faces supposed to make us smile. The weird yellow circles with the arched mouths and dead black ovals for eyes, slapped on everything from school binders to rear bumpers and hippie asses, didn’t elicit the warm-and-fuzzy feelings intended, not for me. No more do those favorite emojis on social media today, really just variations on a smiley, make me trust the opinions they’re used to express.

Still feeling left out of the cute party and looking back for some explanation, I’m forced to admit I was never an easy child. Those Margaret Keane portraits of boys and girls with eyeballs about to explode, cradling kittens and puppies no less deformed, left me numb. A popular clown print gave me nightmares until my mother removed it from my room. As a young adult, I recoiled in terror when housewives started making their own Cabbage Patch Kids, consoled by another development confirming my suspicions of saccharine had not been unfounded. Smiley faces were being stamped on ecstasy tablets.

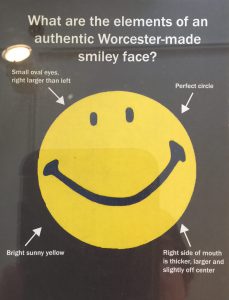

I should also admit, ranked by concentrated cutesiness, the ‘original’ smiley faces that launched a fad and first bothered me as a kid didn’t pack the punch of what they would devolve into. Looking closely at the 1963 icon, one can’t help but note something less than our eyes have since been trained to expect. Allowing for some variation, old (vs. new) smilies tended to have humanlike features that were, so to speak, less juvenile and more adult in appearance—which is to say, less cute, and less scary for me than what took their place. The eyes weren’t yet those gaping abysses, like a greedy brat’s in a candy store, but smaller and casually off-center, one larger than the other, suggesting both a knowing wink and a pubescent peep. The smile itself was also asymmetric at first, less generic in feeling, thicker on one side, more a sly or contented grin than an incitement to prefab gleefulness.

More striking still, the space under the smile was larger, leaving room in our imagination for a strong and fully-developed jaw, and above the eyes was space only for a small forehead, not the raised, almost cartoonish brow of an infant. All adult traits these were—not cute ones—if transferred onto a real human face. The overall look, whether intended or not, was distinctly more staid than what would follow, a good thing because the image was designed by an artist hired specifically to induce mild euphoria, not zaniness, in employees of an insurance company stressed over recent mergers and acquisitions and likely bored with their jobs.

There’s no proof that the bright-sunny-yellow orb with the jaundiced grin employed to “raise morale” actually increased productivity or happiness, but the style was clearly different from today’s standard smiley with the hyperbolically curved mouth, dilated psychotic glare, and fearful symmetry. I suspect anyone susceptible to a smiley’s charms built up a resistance to the old and demanded some new-and-improved version of cute, as they would crave higher potency in many commercial products, such as painkillers, energy drinks, and sugary breakfast cereals, fodder for a joyless hunger to have a nice day.

Am I taking simple smiley faces a tad too seriously—or is everyone else? The sorts of observations I’ve just made on those little yellow fellows have been documented, more extensively on other subjects, by minds greater than mine. Harvard historian of science Stephen Jay Gould built upon the work of a renowned ethologist and zoologist when he did a playful but not gratuitous analysis of another American icon, Mickey Mouse, the famous cartoon character who underwent a similar transformation before the smiley face was even born.

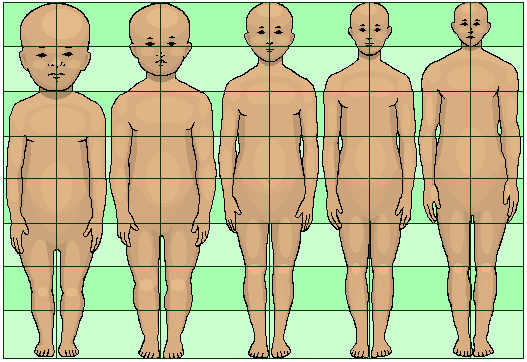

Mickey’s head was also based on a simple circle, re-mapped over the years to suggest a regression to an earlier stage of development, more biology in reverse. Gould used a series of precise measurements and ratios to illustrate how, during his first fifty years after coming alive at Walt’s hand, Mickey’s visual style changed slowly but radically, a devolution into the innocuous beanbag we know today. The slippery little rodent with the long, snipey snout, the small, beady eyes, the low, criminal brow, and an agile body capable of much mischief, who made my parents laugh before the main feature played on the silver screen back in the 1930s, was a far cry from the idealized plastic figurine with the heavy head bobbing over my birthday cake in the 1960s, now a vintage heirloom on someone’s eBay page.

The older Mickey’s ears were gradually ripped back to expose the forehead of a helpless infant. Eyes were swollen as large as any Margaret Keane puppy’s. The snout was crushed to be less wolfish than Wiley Coyote’s, more puggish like a pudgy angel’s button nose. The entire head in relation to the body was infantilized, an enormous bulb bolted to a diminutive body with long, wiry, mobile, unpredictable arms and legs reduced to the fat, dwarfed, lame stumps of a Teletubby or a French bulldog.

“The original Mickey was a rambunctious, even slightly sadistic fellow,” wrote Gould. “In a remarkable sequence, exploiting the exciting new development of sound, Mickey and Minnie pummel, squeeze, and twist animals on board a steamboat to produce a rousing chorus of ‘Turkey in the Straw.’” All around, the new-and-improved Mickey of later years looked more compact and rounded than edgy, less threatening—but not necessarily more mature—than in his youth, better suited to bouncing and rolling than swinging cats by the tails, precisely the opposite of what we’d expect from a full-grown predator. But he did look acutely cute.

Accompanying Mickey’s kinder-and-gentler look were behavioral changes. The early, lean-and-mean miscreant didn’t shy away from confrontations and gladly scrapped over what he wanted. He taunted and returned to torment a giant feline bully who got in his way. He pulled, choked, and hammered a happy tune out of several other animals—only to end as an inoffensive, body-shame-able marshmallow of a marching band leader for The Mickey Mouse Club in the wholesome 1950s. Mickey grew as helpless as the Baby Jesus in swaddling clothes. Those harsh grunts and squeaks that got the point across in his early work became the most humble Midwest-American English spoken in the soft, high-pitched voice of a small child.

The sharp-nosed, hard-assed commander of a steamboat that docked briefly at a town unapologetically labeled “Po Dunk,” grew more sensitive and inclusive, with child acolytes singing his praises on television, wearing plastic mouse ears and assuring us that “through the years we’ll all be friends wherever we may be” in a small, small world. “Y? Because we like you.” I still have nightmares. Mickey’s emasculation and jolly eunuch manner set in too slowly to be noticed in real time, at least partly unconscious adjustments to changing styles and new standards for entertainment. But his untoward antics were increasingly frowned-upon in no uncertain terms, concerned mothers and organizations upholding the nation’s moral hygiene in letters to Disney Studios warning this was not the mascot they wanted greeting youngsters at the Magic Kingdom. Alarmists were taken seriously by creators who toned down the little rascal lest anyone be offended, perhaps an early prototype for politically-correct censorship.

The very name “Mickey Mouse” is still used derisively as an expression for things not to be taken seriously, as in: “That company’s a real Mickey Mouse operation.” So why, apart from selling family vacation packages, would anyone want to encourage wimpiness, not only in children but in adults who live to cater to them? Not because we like you, but because we like those warm-and-fuzzy feelings you give us when you’re all dimply and don’t show too much spirit. The quest for a sugar rush is taken quite seriously by those who crave it. Animated national heroes aside, juvenile traits are enhanced in real animals, human and non-human, forcing them into a pleasing state of arrested development. Gould, again, expanded on the great founder’s work on appearance, behavior, and growth. Humans in fact evolved to be juvenile, he wrote, going so far as to call us an underdeveloped species.

Normal humans do grow up to look and act more adult and less cute than their coddled offspring, but the contrast is more pronounced in other animals. The most obvious difference between us and ‘lower’ primates is our higher forehead, not the flat, apish brow that comes with maturity. We never quite attain the fully projected jaw of a chimp, either, which keeps us looking all the more cuddly. Our appearance and behavior also change more slowly. Post-natal development is longer for very big brains, and we keep learning for much of our lives while other animals are less open to new experiences—at least that’s the theory. Our gestation period is the longest of any primate, and once we’ve finally left the womb, we don’t want to leave the nest. Many of us are able to digest lactose well into adult life, good news for latte lovers and mama’s boys. We have by far the longest childhoods, when necessity doesn’t force us out, big business for pushers of four-figure baby strollers. On average, we mooch off our parents for periods obscene by the rest of nature’s standards. Thanks to child labor laws, new health insurance provisions, and devalued college degrees, today’s guppies enjoy extended juniorities, and from the looks of things could be set up for life-long huggability.

Why do we support such lavish suckling? From their debut performances ex utero, humans begin mastering the art of demanding attention and care. While females are more likely to get goo-goo over a cute face or childish demeanor, the appeal of baby-talk isn’t exactly a chick thing. Males can be, or are pressured to be, pussies for a kid that comes out looking not too ugly (or that looks like one), but they may be less motivated to get involved in caring for the wide-eyed little critter. This suggests the “cute response” may be universal, while the long-term follow-up, after that initial rush of warm-and-fuzzy feelings, well, maybe not.

Not even “a face that only a mother could love” is guaranteed the real goodies. On the contrary, studies show the way a mother treats an infant can be predicted based on its “babyish” appearance or “attractiveness,” and whether it makes those plush squeaky sounds associated with good health. Looks and crying styles that fall short of expectations can affect a mother’s level of attachment, nurturing, even lactation. Cuteness is no joke.

Historically and across cultures, newborns have had better chances for a future, for getting those initial breaks they need and not getting strangled or flushed, if they’re roly-poly butterballs, the rounder the better, with Cabbage Patch cheeks and ample fat right down to those chubby Teletubby fingers and toes, all signs that they’re worth the input. Add a killer smile, “an elaborate configuration of the ancient primitive open-mouth invitation to play,” and that babe’s on the road to survival. Gut-level responses to cute seductions, tests have shown, make us more focused and effective at performing tasks, which could only decrease our chances of dropping Baby Dumpling on his head. A sweet mug can make us want to nurture and protect, good for the species to flourish, good or bad for the rest of the planet.

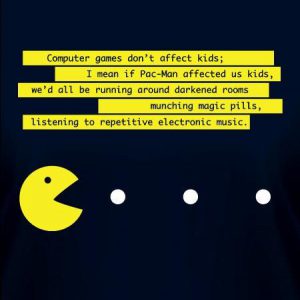

So being cute is not just to be cute, but has a strategic, even brutal side. Mickey Mouse’s slow castration, and a broader purge of “harmful” children’s entertainment, at some point joined hands, like the Waltons at suppertime—I cringed when my mother tried this on us—with a popular misconception that the sort of stylized violence in media was actually causing aggressive behavior and making America unsafe.

It would have made no more difference to alarmists in the 1970s–when crackpot psychologists began generating mass hysteria and launched a witch-hunt for subliminal demons in Saturday morning cartoons–to find evidence to the contrary, than it does to crusaders to be told there’s no more definitive proof now than there was back then. As with so many media-generated non-issues, a host of other factors, obvious political agendas, and a much bigger picture have been ignored. The assumption is still made that since bad things happen in the world, then, in modern academic parlance, the testosterone-driven, Caucasian, cisgender, heteronormative, capitalist-imperialist patriarchal media simply must be playing a role—a prescription for that spoonful of sugar whether we want it, or the medicine, or not.

Violent crime did skyrocket in the sixties and on through the seventies and eighties, but could scarcely be blamed on Sylvester swallowing Tweety and belching a feather, the sort of gag promptly outlawed by the new cartoon police. Rascally behavior was in fact rising over the very decades when children’s shows were being mollified, apparently with opposite the intended effect.

What were reformers so afraid of? Slapstick, which got its name from a device that Vaudeville actors used to hit each other on stage, was around a long time before labeled unfit for consumption. Some of my fondest childhood memories are of my grandfather laughing his ass off with me in front of the T.V. whenever Moe used two fingers to poke another stooge in the eyes. I’ve never known anyone from our generations, or my parents’, to wear an eye patch.

Video games spawned more alarmists, not just because they were getting palpably gory and involved rapid-fire guns, but because they were interactive, which made them more dangerous, or so it was said. Not only is this theory still questionable, but during those same years that violent, “misogynistic” video games were taking off, and the media in general depicted carnage more realistically and grew more sexually permissive, violent crime and rape actually plummeted. Years and studies later, it’s far from certain that childhood exposure to two-dimensional shenanigans leads to 3D misconduct, or to criminal behavior later in life.

Searching for early influences, not many people believe that Lou Reed, the man who made rock music more “adult” and a childhood idol more to my taste than Mickey Mouse, was actually to blame for turning an entire generation into “junkie faggot freaks,” as one critic claimed. Yet no amount of inconclusive evidence in the world on the would-be effects of media violence has prevented my baby-boomer peers from burdening society with a whole crop of uptight, pain-in-the-ass, neo-Victorian ninnies weaned on lame entertainment and scared of their own shadows.

Clinging to their belief that the antics of Bugs and Scooby must have been contributing to naughtiness and worse, they set out to cleanse the spirited classics of toxic masculinity, stripping characters of character, or effectively banning them from the Saturday morning menu. Virtual role models were designed to be docile, bland, and nurturing but in a cheap, cloying, underhanded way, their drab, frumpish, pared-down personalities as flat and unpainterly as the computer-generated style of animation that was dominating the cartoon landscape. Any unkind or fightin’ words became anathema, as did playful pokes, punches, slaps, kicks, dynamite, nitroglycerine, earthbound anvils or pianos—everything that made childhood fun—all bad influences removed from the nursery.

Dealing with the aftermath today, I can honestly say that I share nothing, and have nothing to talk about, with the Care Bear generation. Healthy exceptions like South Park, The Simpsons, and video games aside, college students have been raised on a strict, gender-free diet of anodyne schlock and touchy-feely “multiculturalism.” They’ve been methodically trained, not to make unsettling discoveries or form provocative ideas, but to spend their lives seeking out material they deem “offensive,” either to them or conceivably to someone else on the planet, an expanding list of faux pas they ferret from every nook and cranny and dutifully report for blacklisting. Talking to millennials is like reporting to those small-minded, sadistic nuns who ruled us with a ruler in Catholic school. Literally everything is shocking to the new kids on the block, and it’s impossible to have a spontaneous, unedited exchange with them. Their idea of humor, if it can be called that, is guarded and stilted, not bold or edgy, and certainly not liberating. Landmines are everywhere in their minds, and unintended slip-ups from grown-ups are duly noted by the Emily Post-its.

“Waitress,” as a proud, paying father is “educated” over dinner at New York’s pricy Café Loup by his outraged post-grad son, has been dropped in favor of “server,” said to be the more appropriate term, but far more demeaning, I’d say (and I did).

“Asian,” I was taught one day by an NYU twit serving me at Pier 1 Imports, a retail chain specializing in fruits of child labor and slave wages in third-world—sorry, underdeveloped—sorry again, developing—nations, was the acceptable term for “Oriental,” only just listed as “racist.” More concerned with stylistics than substance, Care Bears hibernate year-round in a cubbyhole world where all corners must be rounded, or padded, as I remember the furniture in a relative’s home when she first started spawning these prickly powder puffs. I tried to convince her that nurturing had jumped the tracks, that absolutely no one we knew had ever been blinded by a coffee table, but to no avail. I still blame Thomas the Tank Engine, yet another permutation of a smiley face and the most insipid invention in all of human history, for her second boy being diagnosed “mildly retarded”—sorry again: mildly intellectually disabled.

It couldn’t have been easy for this last generation to be made experimental victims of crap psychology and over-cautious fussbudgetry, and it’s no surprise these kids don’t want to go outside and play like big boys and girls. Graduating from Thomas the Tank Engine to Grand Theft Auto must have mixed their signals, and perhaps the only true effect of media on behavior has been a growing epidemic of PTSD, our latest disorder du jour. (A half-century since we ended the draft, it’s unlikely most of these whiners have ever experienced real trauma.)

As for grown-up fun, millennials don’t really like sex unless it’s virtual, or they might get off if dressed as stuffed animal toys or trained as puppies. Otherwise, they are quite paralyzed, from the waste-down and neck-up, to the point that feelings have become more important than facts. Witness the invasion of ♥s—I hate f#@king ♥s—on social media. Sticking a grade-school star for “excellent” on a simplistic message composed in internet haiku apparently wasn’t pat-on-the-head enough. Not only are you not asked to explain why, you can no longer simply like but must absolutely love a tweet poem, and maybe send a hug, for the tweeter poet to feel personally validated.

Nature or nurture? A lot of testing on user response goes into the design of social media characters, just as market researchers have long understood how to push our evolutionary buttons. A growing range of products, from Mini Coopers and VW “bugs,” to M&Ms and Cavalier King Charles Spaniels, owe their success to being born rounded, wide-eyed, or somehow goofy and cutesy. The strategy has been to conjure juvenile images of innocence, sincerity, weakness, vulnerability—even if these translate into actual deformity and disability—which humans find irresistibly cute, then to funnel their nurturing responses into cash flow, encouraging behavior that can work against us and requires unlearning. The cute craze continues to mature into something less and less endearing, despite warnings long ago, from that Nobel Prize-winning scientist who inspired Stephen Jay Gould to take Mickey Mouse seriously, of a distinct difference between a “genuine” or “innate” biological response, and the “biologically erroneous” or “inappropriate” kind.

Like it or not, cute is not only no joke but serious business, and big business, because this stuff works. As the internet has grown conspicuously cute, whether it has made us smarter, or even more in touch with our emotions, is a matter of perspective. Grumpy Cat memes aside, the most popular emojis, as they’re called by the Japanese, who are black-belts in cute, or the sketchy equivalents called emoticons, are the latest generation of smiley faces. Thrown in for added fun are ♥s, hand signals, clowns, aliens, animals, people wearing animal ears, trains, planes, automobiles—even a pile of poop with cute eyes—but the preferred icons are smilies, now customized to sound the vast catalog selection of human depth and validate every conceivable shade of our rainbow diversity. It gets very personal, at least superficially. Smilies have different smile styles. They cry different types of cartoon tears. There are separate genders, skin tones (“light”/“medium”/“dark”), and types of ethnic headgear from which to choose. Last I looked, there was still no black-faced minstrel emoji, and despite the numbing variety of choices, as in childhood I find myself left out of the cute party.

In fact it made me feel sad inside when Facebook, after teasing with the hint of a basic, no-nonsense “thumbs down” for things that ticked me off—a surefire trigger for hurting someone else’s feelings (though likely the opposite of what it meant in ancient Rome)—didn’t come through with that perfect option to the all-or-nothing positive keystroke, the “thumbs up.” Instead, we got the entire non-binary bundle of smilies I still refuse to use, with features like eyebrows, teeth, and tongues added to enhance our emotions and clarify our feelings. Responding to posts or comments, we can now express various degrees of euphoria, surprise, rage, or uncertainty, all curvy and cute-coated to keep it playful.

Even hate, the opposite of ♥, and apparently all that’s wrong with this troubled world of ours today, can be softened with a global cartoon face. When holders of ♥-felt opinions are brave enough to reveal the identity behind so much soul-baring, their photographed faces are often converted into cartoonized thumbnails, today’s virtual business cards. The goal of coloring-book caring is to edge around anything as direct as a Vaudevillian pie-in-the-face, to sidestep outright rejection, however negative or red-faced your smiley, to demand others be as sensitive toward your feelings as you’ve just been toward theirs.

Of course, the companies who put so much marketing research into characters used to express how we’re feeling, from one moment to the next, on world affairs or whatever, aren’t motivated by a sense of charity or altruism. The bottom line is not promoting a progressive ideology, or protecting our feelings. Facebook, Twitter, and other “communities” don’t want their members feeling hurt and storming out in a huff. Baby-faced billionaires have a lot invested in cuteness and they need to keep selling us cute stuff.

Finally, another juvenile trait is the demand for quick rewards without work or sacrifice, and since posting an estimated reading time up-front would have scared most readers away from this essay, I’ll play fair and wrap it up.

Behind those smiley faces, I’ll say again, is something grim, and learning later in life that it wasn’t just me, that icons are, indeed, open to interpretation, has been no solace. As an author and journalist, I remember feeling disappointed and demoralized to see intellectuals I respected, fellow writers, and heads of the few remaining serious, independent publishing houses, finally jump ship and hop in the clown car with the kiddies. After mocking the latest video games, they lowered themselves to Facebook, and worse, Twitter, a forum that reduces the most complex ideas to the slick, smug brevity of an advertizing pitch, where knowledge is vast but shallow, truth is based on consensus, and almost no one reads beyond the catchy one-liners, or a tangled mess of links added to reinforce gut feelings.

People of all ages are now on social media, sticking their tongues out at political candidates, crime statistics, and foreign policy decisions, and being part of a Mickey Mouse operation is no longer frowned upon but expected. Likewise for tattle-telling on someone who said a bad word or expressed some inconvenient truth—based on this week’s consensus—sissy behavior once considered cowardly and dishonorable but now the norm. The cuter the internet gets, the more restrictive, reductive, and dangerous it grows. Baby-faced billionaires don’t want members logging off and running home crying real tears, and so encourage them to self-censor, turning Pac-Man, a smiley face in profile, into a ravenous pack of wolves.

Perhaps our initial belief that computers would magically do all our thinking for us—hopefully, without rising and enslaving us—was an excuse to get lazy and hypersensitive, crushing with cartoon gestures any threats to our comfort zones. Alternatively, feel-good psychology fads launched from our highest seats of learning, abetted by a press always trying to sell us outrage and shame—and viral videos raising danders and inspiring mass movements that sprout as fast as they wither—surely played a role in shaping social media into what it is today: a humongous rubberized playground at recess time, childproofed and chaperoned but where schoolyard bullies are free to mark targets, gossip spreads fear, fear turns to aggression, posses form in seconds, and kangaroo courts decide, with GIF-generated bounciness, if offenders should be excommunicated and silenced, careers cut short and lives ruined, because something was said that kept someone from having a nice day.